Bern Riddle 26: De sinapi

NEVILLEMOGFORD

Date: Sat 28 Nov 2020Matching Commentaries: Commentary for Bern Riddle 26: De sinapi

Me si visu quaeras, multo sum parvulo parvus,

Sed nemo maiorum mentis astutia vincit.

Cum feror sublimi parentis humero vectus,

Simplicem ignari me putant esse natura.

Verbere correptus saepe si giro fatigor,

Protinus occultum produco corde saporem.

If you look for me, I am teeny-weeny,

but no one larger is more cunning than me.

When I am carried on the shoulder of my lofty parent,

the ignorant think that I am of a simple nature.

If, when captured, I am often beaten and worn down by a circle,

I immediately produce a hidden flavour from my heart.

Notes:

This edition is based on Karl Strecker, ed., Poetae Latini aevi Carolini, Vol. 4.2 (Berlin, MGH/Weidmann, 1923), page 746.

A list of variant readings can be found in Fr. Glorie, ed., Variae collectiones aenigmatum Merovingicae aetatis, Corpus Christianorum, Series Latina 133A (Turnhout: Brepols, 1968), page 572.

Tags: latin Bern Riddles

Commentary for Bern Riddle 26: De sinapi

NEVILLEMOGFORD

Date: Mon 08 Feb 2021Matching Riddle: Bern Riddle 26: De sinapi

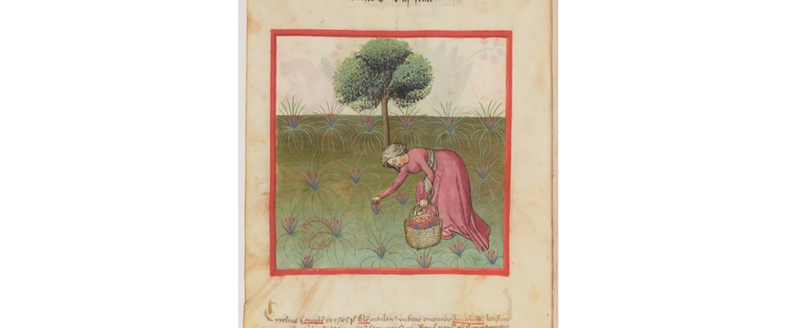

This riddle is a hymn to a tiny thing with a big taste—the humble mustard grain!

Mustard was a much-loved flavouring in ancient and medieval Italy. It was also used in pre-Conquest England, although the relatively small number of archaeological finds and recipes would suggest that it was not as popular in England as it would become in the High Middle Ages (Banham, p. 39). One English text mentions mustard as a food suitable for those suffering from nausea and refers to ða gelicnesse… ðe senop biþ getemprod to inwisan (“the form which mustard is mixed for flavouring,” Cockayne, page 184). The appearance of mustard in the Bern Riddles sometimes has been taken as evidence of southern European origin (Klein, page 404), but this is not certain.

The riddle’s central conceit is that the tiny mustard seed carries a powerful “hidden flavour” (occultum…saporem) in such a small body. Line 1 uses an irregular comparative phrase, multo sum parvulo parvus, which I have translated idiomatically as “teeny-weeny.” The second line puns on the word astutus (“cunning”) and acutus (“sharp”), and I wonder whether the original was ‘no one larger is sharper than me,’ since mustard is not exactly known for its cunning.

Line 3 might give you déjà vu (or should that be Dijon vu?) since, for the second riddle in a row, we are invited to guess the riddle subject’s parentage. The “lofty parent” (sublimis parens) is the mustard plant, which can grow to head height in its flowering and ripening stages.

The final two lines explain the preparation and consumption of the mustard seed. The torture of line 5 might sound violent, but it refers either to the mustard’s preparation with a mortar and pestle, or to its chewing. Line 6 leaves us with an idea that is very much in keeping with the spirit of medieval riddling—a hidden thing, which requires hard work to uncover, but which leaves you with a pleasant taste. Much like a riddle, actually!

References and Suggested Reading:

Banham, Debby. Food and Drink in Anglo-Saxon England. Cheltenham: Tempus, 2004.

Cockayne, Oswald (ed.). Leechdoms, Wortcunning, and Starcraft of Early England, Volume 2. London: Longman, Green, Longman, Roberts, and Green, 1865. Page 184. Available here.

Klein, Thomas. “Pater Occultus: The Latin Bern Riddles and Their Place in Early Medieval Riddling.” Neophilologus 103 (2019). Pages 339-417.

Tags: latin Bern Riddles

Related Posts:

Bern Riddle 25: De litteris