Exeter Riddle 46

VICTORIASYMONS

Date: Wed 21 Oct 2015Matching Commentaries: Commentary for Exeter Riddle 46

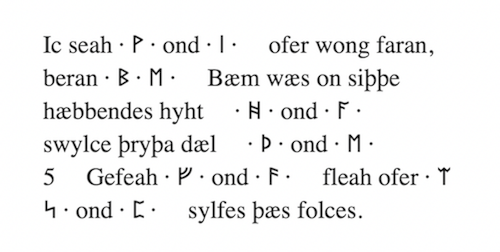

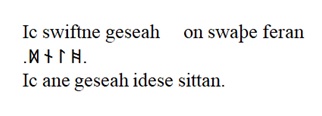

Wær sæt æt wine mid his wifum twam

ond his twegen suno ond his twa dohtor,

swase gesweostor, ond hyra suno twegen,

freolico frumbearn; fæder wæs þær inne

5 þara æþelinga æghwæðres mid,

eam ond nefa. Ealra wæron fife

eorla ond idesa insittendra.

A man sat [drinking] wine with his two wives

and his two sons and his two daughters,

the dear sisters, and their two sons,

noble firstborns. The father of each

5 of those princes was in there,

uncle and nephew. In all there were five

warriors and women sitting within.

Notes:

This riddle appears on folio 112v of The Exeter Book.

The above Old English text is based on this edition: Elliott van Kirk Dobbie and George Philip Krapp, eds, The Exeter Book, Anglo-Saxon Poetic Records 3 (New York: Columbia University Press, 1936), page 205.

Note that this edition numbers the text Riddle 44: Craig Williamson, ed., The Old English Riddles of the Exeter Book (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1977), page 97.

Tags: anglo saxon exeter book riddles old english solutions riddle 46

Related Posts:

Commentary for Exeter Riddle 46

Exeter Riddle 9

Exeter Riddle 42

Commentary for Exeter Riddle 46

VICTORIASYMONS

Date: Wed 21 Oct 2015Matching Riddle: Exeter Riddle 46

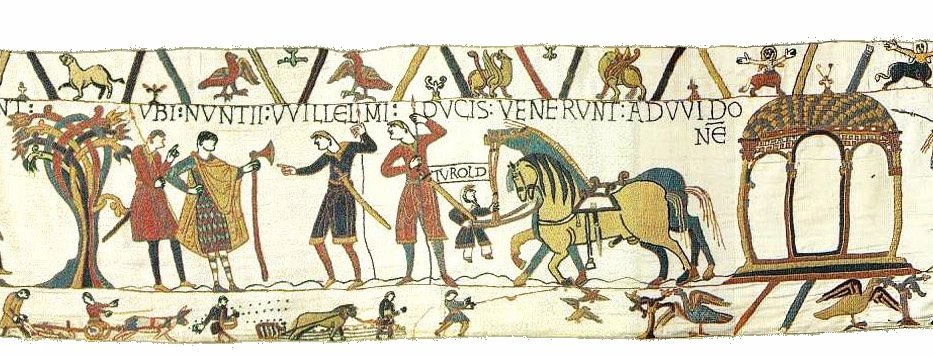

At first glance, following on from two very explicitly sexual riddles (“þrindende þing,” indeed), Riddle 46 is almost disappointingly tame – just a family having dinner together. In fact, it is anything but. It may not look like it, but what we have here is yet another riddle that, once again, is all about sex.

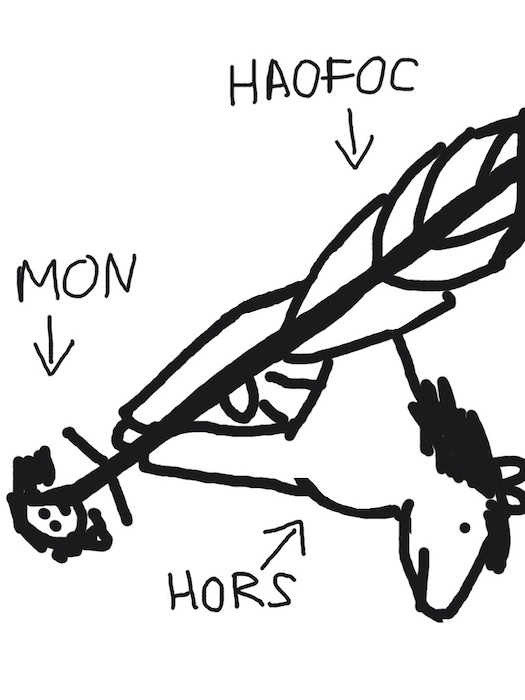

It starts with a situation familiar from Old English poetry: a man sitting down to a drink. Keeping him company are his wives – yes, both of them – his two sons, his two daughters, their two sons, and each sons’ father, uncle and nephew. It’s quite a gathering! Except, as we learn in the final line, there are only five people in the room. Like the Tardis, this is a family that’s bigger on the inside.

Relevant. Photo (by Steve Collis) from the Wikimedia Commons (licence: CC BY 2.0).

The test of the riddle, then, is to work out how this small group can have quite so many relationships binding them together. The answer starts with sex: this family’s been having rather a lot of it.

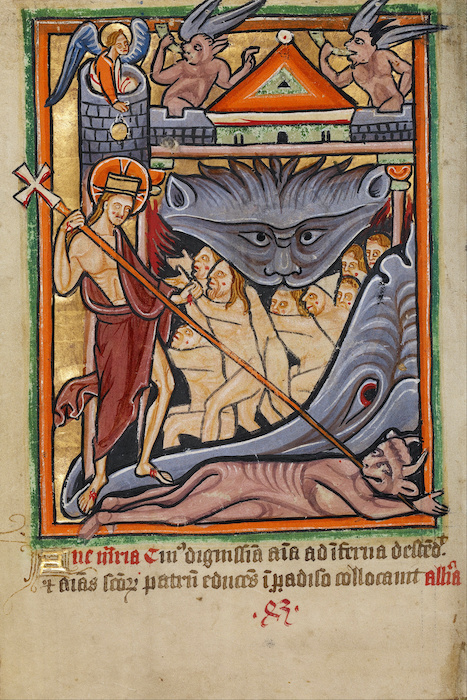

Something about incest seems to lend itself to riddles. In Apollonius of Tyre, which was translated into Old English in the eleventh century, the “wicked” King Antiochus requires his daughter’s potential suitors to solve a riddle about his incestuous relationship with her (Lees, pages 37-9; for other examples see Bitterli, pages 57-9). The source material for the similarly incestuous set-up of Riddle 46 is found in the Bible (where else?). After fleeing the destruction of Sodom and Gomorrah, and leaving his wife behind as a pillar of salt, Lot finds himself holed up in a cave, together with his two daughters:

And the elder said to the younger Our father is old, and there is no man left on the earth, to come in unto us after the manner of the whole earth. Come, let us make him drunk with wine, and let us lie with him, that we may preserve seed of our father. And they made their father drink wine that night: and the elder went in and lay with her father: but he perceived not neither when his daughter lay down, nor when she rose up. And the next day… They made their father drink wine that night also, and the younger daughter went in, and lay with him: and neither then did he perceive when she lay down, nor when she rose up. So the two daughters of Lot were with child by their father. (Genesis 19:31-36)

So there you have it. The riddle’s five people are Lot himself, his two daughters, and their sons by him. That makes the boys both the sons of Lot, the sons of his daughters, and each others’ uncle and nephew. Everything is accounted for!

Or at least, almost everything. There’s one relationship in the riddle that doesn’t appear in the Genesis story. In Genesis, Lot is seduced by his daughters, but he doesn’t marry them. In Riddle 46, however, they are referred to as his wifum twam. A reference to multiple wives would, I think, have particular connotations for an early medieval reader. There’s evidence to suggest that, before the Conversion, it was accepted for early English men to have several wives, or concubines (Clunies Ross; Lees). The practice persisted well into the Christian era, although the church was most certainly not ok with it:

Se man ðe rihtæwe hæfð ond eac cyfese ne sylle him nan preost husl ne nan gerihto þe man cristenum mannum deð butan he to bote gecyrre. (Frantzen, Old English Penitential, 2.9)

([Concerning] the man who has a legal wife and also a concubine, let no priest give him the eucharist nor any of the rites which are performed for Christian men, unless he turns to repentance.)

Furthermore, Margaret Clunies Ross argues that polygamy was “practiced much more extensively among the upper classes [of early English society] … than in the lower social ranks” (page 3), and Clare Lees describes “serial polygamy and concubinage” as “the prerogative of the ruling family of the West Saxons’ (p. 37). It’s fitting, then, that the characters of Riddle 46 are described variously as freolic, ides, æþeling and eorl: all terms with a predominantly aristocratic flavour.

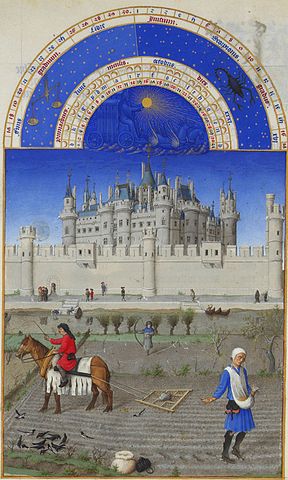

Now you may find yourself wondering how the early medieval church justified its stance on concubines (not ok), when there’s polygamy a plenty in the Old Testament – as this riddle itself demonstrates. And you wouldn’t be alone. Ælfric specifically discusses this point in his Preface to Genesis:

On anginne þisere worulde, nam se broþer hys swuster to wife and hwilon eac se fæder tymde be his agenre dehter, and manega hæfdon ma wifa… Gyf hwa wyle nu swa lybban æfter Cristes tocyme, swa swa men leofodon ær Moises æ oþþe under Moises æ, ne byð se man na cristen.

(In the beginning of this world, a brother took his sister as a wife, and sometimes also a father had a child with his own daughter, and many [men] had multiple wives… [but] if anyone wishes to live now, after Christ’s coming, in the same way that men lived before Moses’ law, or under Moses’ law, that man is not a Christian.)

Ælfric’s argument is that things were different back in the day, and Old Testament practices can’t simply be copied without some interpretation. By presenting an Old Testament story in the guise of contemporary medieval culture, I think our riddler is making a similar point. Take the Old Testament literally, and next thing you know you’ll be sitting down to dinner with your brother-uncle. No one wants that.

Read in the context of these penitentials and homilies, we can see how this riddle engages with some pretty topical social issues. Both the specific subject of marriage, and the more general dangers of incorrectly interpreting Biblical material, are touched upon here, with perhaps a bit of a jab at the upper classes thrown in for good measure. As Jennifer Neville summarises, it’s not every day you find a Bible story repackaged into a joke about sex, masquerading as a number game!

But there’s another way that we can read this riddle, too. For all its playfulness, there’s an underlying suggestion of something darker going on. Because, of course, the story of Lot is not simply the story of a man with one too many wives. It’s also a disturbing narrative about incest and exploitation. And I don’t think that’s lost on the author of this riddle.

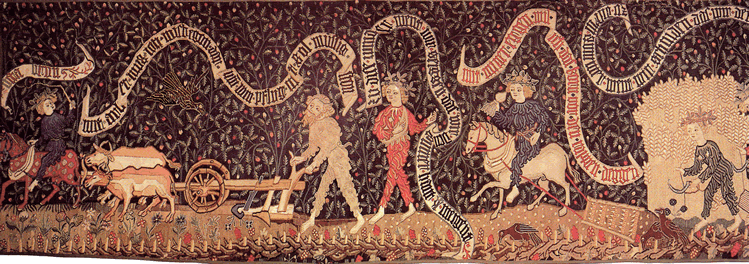

We get our first sense of this with the reference to wine in the first line. This detail comes straight from the Genesis story, so in one way it gives us a hint about the riddle’s solution (Murphy, page 144). But it also draws attention to the role played by alcohol in all of this. Drinking was, of course, a not uncommon pastime in early medieval England, but nor was it universally celebrated (see Riddle 27, for example). The poem Judith, another Old English adaptation of an Old Testament story, firmly links drunkenness with sexual wrongdoing.

This is where too much drinking gets you in Judith. Image of painting by Caravaggio from the Wikimedia Commons.

The words inne and insittendre place a particular emphasis on the interiority of the setting in this riddle. Combined with the insistent repetition of ond in the opening and closing lines, the poet creates an unsettlingly claustrophobic atmosphere. This is a family that, behind closed doors, is rather too close for comfort.

Now, the Genesis story very clearly presents Lot’s daughters as the incestual instigators, up to and including getting their father insensibly drunk first. That’s problematic enough, but Riddle 46 complicates things even further. Here, the father is presented in a much more central role; the words wær and fæder are positioned prominently at the very start and exact middle of the poem, while the three-fold repetition of his in the opening lines emphasises his authority over everyone else present. It’s a subtle change, but it’s one that encourages us to consider the complexity of the power dynamics at play. In combination with its claustrophobic atmosphere and suggestion of drunkenness, the riddle hints at the more troubling implications that undercut the narrative’s superficially playful presentation.

When reading the Exeter Book riddles, it’s always worth having a look at what’s near them in the manuscript. In this case, Riddle 46 follows hot on the heels of two explicitly sexual riddles, full of raunchy imagery and innuendo-laden puns. Riddle 46 continues the focus on sex, but explores it in a much broader way: in relation to society, to the Bible, to families, and to power. It’s at once short and playful, but also serious and, I think, pretty dark. Not bad for a little poem about family dinner!

References and Suggested Reading:

Ælfric. “Preface to Genesis.” In The Longman Anthology of Old English, Old Icelandic and Anglo-Norman Literatures. Edited by Richard North, Joe Allard and Patricia Gillies. London: Routledge, 2014, pages 740-45.

Bitterli, Dieter. Say What I Am Called: The Old English Riddles of the Exeter Book. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2009.

Clunies Ross, Margaret. “Concubinage in Anglo-Saxon England.” Past & Present, vol. 108 (1985), pages 3-34.

Frantzen, Allen J., ed. The Anglo-Saxon Penitentials: A Cultural Database. 2003-2015. http://www.anglo-saxon.net/penance/index.php?p=index

Godden, Malcolm. “Biblical Literature: The Old Testament.” In The Cambridge Companion to Old English Literature. Edited by Malcolm Godden and Michael Lapidge. 2nd edn. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2013, pages 214-33.

Lees, Clare A. “Engendering Religious Desire: Sex, Knowledge, and Christian Identity in Anglo-Saxon England.” Journal of Medieval and Early Modern Studies, vol. 27 (1997), pages 17-46.

Murphy, Patrick. Unriddling the Exeter Riddles. University Park, PA: Penn State University Press, 2011.

Neville, Jennifer. “Joyous Play and Bitter Tears: The Riddles and the Elegies.” In Beowulf and Other Stories: A New Introduction to Old English, Old Icelandic and Anglo-Norman Literature. Edited by Richard North and Joe Allard. London: Pearson, 2007, pages 130-59.

Swanton, Michael, trans. “Apollonius of Tyre.” In Anglo-Saxon Prose. London: Dent, 1975, pages 158-73.

Tags: anglo saxon exeter book riddles old english solutions riddle 46 victoria symons

Related Posts:

Commentary for Exeter Riddle 27

Exeter Riddle 27