Bern Riddle 34: De rosa

NEVILLEMOGFORD

Date: Sat 28 Nov 2020Matching Commentaries: Commentary for Bern Riddle 34: De rosa

Puchram in angusto me mater concipit alvo

Et hirsuta barbis quinque conplectitur ulnis.

Quae licet parentum parvo sim genere sumpta,

Honor quoque mihi concessus fertur ubique.

Utero cum nascor, matri rependo decorem

Et parturienti nullum infligo dolorem.

My mother bears me, beautiful, in a narrow womb,

and, hairy-bearded, she embraces me with five arms.

Although I belong to the humble family of my parents,

I am also honoured everywhere.

When I am born from the womb, I repay my mother with beauty

but not the pain of childbirth.

Notes:

This edition is based on Karl Strecker, ed., Poetae Latini aevi Carolini, Vol. 4.2 (Berlin, MGH/Weidmann, 1923), page 749.

A list of variant readings can be found in Fr. Glorie, ed., Variae collectiones aenigmatum Merovingicae aetatis, Corpus Christianorum, Series Latina 133A (Turnhout: Brepols, 1968), page 580.

Tags: latin Bern Riddles

Commentary for Bern Riddle 34: De rosa

NEVILLEMOGFORD

Date: Tue 09 Feb 2021Matching Riddle: Bern Riddle 34: De rosa

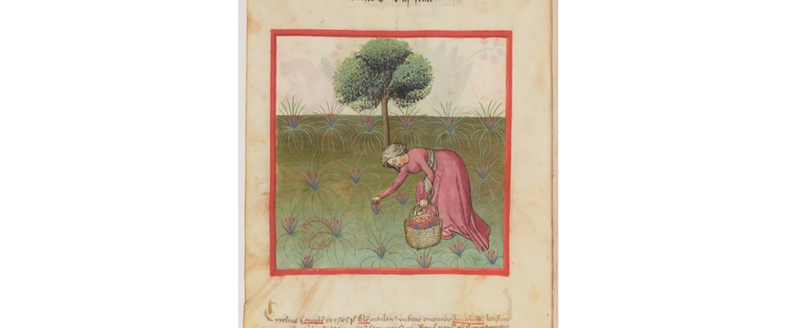

The second of four riddles on flowers, this one tackles several thorny issues. Roses were grown extensively as garden ornaments and for commercial cultivation in ancient Rome, and they became a common plant in medieval monastic gardens. The Plan of St Gall, an architectural drawing of an ideal monastery from the early ninth century, included several gardens, including a physic garden for roses, as well as lilies and various herbs.

As we usually find with other Bern Riddles that use the mother-and-childbirth trope, we are asked to guess the identity of the parent. The mother who bears the beautiful flower in angusto alvo (“in a narrow womb”) is the rose plant, who carries her “child” in the bud. Line two plays upon the meanings of barba, which can mean both “(beard) hair” and the hair on plants. The five embracing arms are the five sepals, i.e. the outer parts of the bud that open, star-shaped, to reveal the flower. The final two lines continue the theme of unconventional childbirth by noting that the rose-child spares her mother “the pain of childbirth” (parturienti dolor).

The riddle continues the theme of noble humility from the violet riddle, explaining that the rose family is both lowly and honoured everywhere. The latter probably refers to its use as a decoration, both in monastic gardens and as a cut flower. It may also allude to the rose’s association with the Virgin Mary, although this is not an overt one.

I mentioned thorns in the introduction, but, unusually for a riddle on roses, it doesn’t actually mention thorns at all. In fact, it is really about the rose flower, rather than the whole plant, which it depicts using themes of humility, beauty, and unconventional childbirth. The saying goes “every rose has its thorn,” but that’s not the case for this riddle!”

References and Suggested Reading:

Touw, Mia. “Roses in the Middle Ages.” Economic Botany. Volume 36 (1982). Pages 71–83.

Tags: latin Bern Riddles

Related Posts:

Bern Riddle 33: De viola

Bern Riddle 35: De liliis

Bern Riddle 36: De croco