Exeter Riddle 18

MATTHIASAMMON

Date: Mon 06 Jan 2014Matching Commentaries: Commentary for Exeter Riddle 18

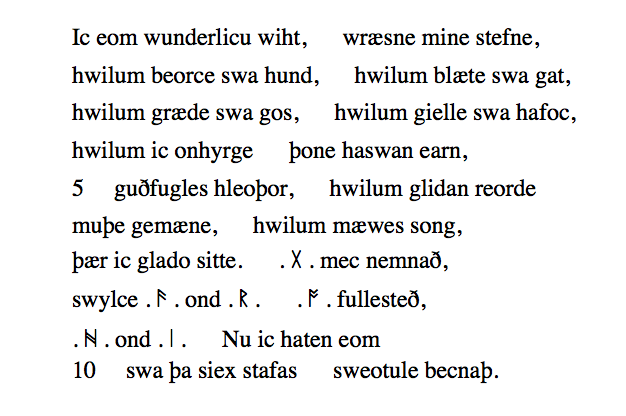

Ic eom wunderlicu wiht; ne mæg word sprecan,

mældan for monnum, þeah ic muþ hæbbe,

wide wombe

Ic wæs on ceole ond mines cnosles ma.

I am a strange creature, I cannot speak words,

nor talk with men, although I have a mouth,

and a broad belly.

I was on a boat with more of my kin.

Notes:

This riddle appears on folio 105r of The Exeter Book.

The above Old English text is based on this edition: Elliott van Kirk Dobbie and George Philip Krapp, eds, The Exeter Book, Anglo-Saxon Poetic Records 3 (New York: Columbia University Press, 1936), page 189.

Note that this edition numbers the text Riddle 16: Craig Williamson, ed., The Old English Riddles of the Exeter Book (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1977), page 78.

Tags: anglo saxon exeter book riddles old english solutions riddle 18

Related Posts:

Commentary for Exeter Riddle 85

Exeter Riddle 19

Exeter Riddles 79 and 80

Commentary for Exeter Riddle 18

MEGANCAVELL

Date: Thu 30 Jan 2014Matching Riddle: Exeter Riddle 18

I know, guys, you’re dying to hear more about this riddle. But word on the street is: it’s kinda short. And so shall you be, commentary. So shall you be.

Solution-wise, most of the options are pretty similar: Jug, Amphora, Cask or Leather Bottle…so, an object for carrying/storing liquid (the Old English word for this sort of vessel is crog). Riddle-editor Craig Williamson points out that there’s archaeological evidence for the transportation of liquids in pottery vessels, although he notes that leather bottles were less likely to be used for shipping (think of the mess!) (p. 184). He also points out that there’s no evidence for wooden casks until after the Norman Conquest…but, then, wood does break down fairly quickly.

An early-5th-to-middle-7th-century pottery jug, © Trustees of the British Museum (licence: CC BY-NC-SA 4.0).

The Inkhorn option also involves liquid, so you can see the relation. Note, however, that this solution doesn’t really account for the ship at the end of the poem. I also personally doubt this one, seeing as the speaker specifically says that it can’t speak, and writing implements in the riddles often riff on the fact that they have the ability to communicate. And finally, WHO keeps suggesting Phallus? Seriously, someone has suggested this for nearly every riddle. Stop acting like school children, riddle-scholars of the past. And get it together.

10th-century Spouted Jug, © Trustees of the British Museum (licence: CC BY-NC-SA 4.0).

Now, things to note: having human-ish body parts but not being able to speak is very common in the riddles. This particular object has a muþ (mouth), which is why I like the Jug- (or Amphora-) reading of the poem. It also has a womb/wamb (belly). This is a very riddley word as far as Old English poetry is concerned. Of the fourteen poetic instances only two are outside of the riddles: Riddles 3, 17, 18, 36, 37, 62, 81, 86, 87, 88, 89, 93, The Phoenix (line 307a) and An Exhortation to Christian Living (line 41b). It also comes up in prose quite a bit. Slight support for the Cask-reading comes in the form of Aldhelm’s Anglo-Latin Enigma 78, Cupa Vinaria (wine-cask), lines 5-7 of which describe the object’s swollen body and innards.

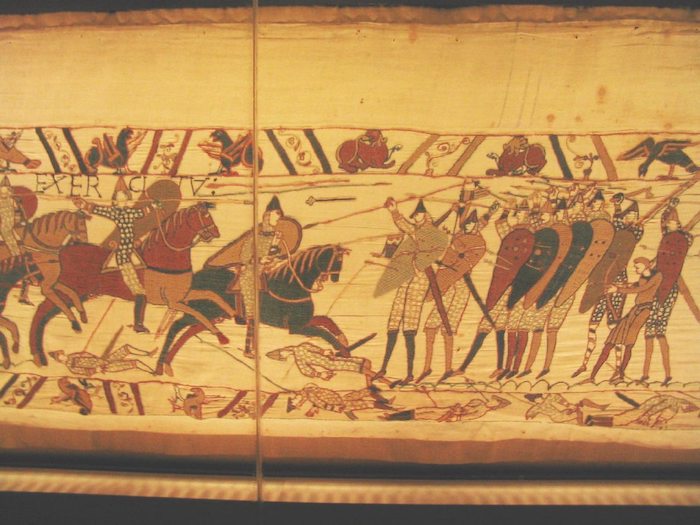

A scene from the Bayeux Tapestry of men carrying arms and a cask on a wagon, excerpted from an image on Wikimedia Commons (public domain).

Another thing to note: self-identified “wonderful creatures” (braggarts) are also pretty common in Old English riddles. In fact, we find the formulaic half-line Ic eom wunderlicu wiht (I am a wonderful creature) applied to riddle-subjects four times: here and in Riddles 20, 24 and 25. Similarly, the half-line Ic wiht geseah wundorlice (I saw a wonderful creature) is repeated at the beginning of Riddles 29 and 87 (here, wiht actually appears at the end of the half-line), while wundorlic is dropped into various other phrases in Riddles 29, 31 and 88. I can’t remember how much I’ve talked about Old English “formulas” in previous posts, but you should certainly get used to seeing these repeated phrases cropping up in multiple contexts (outside of the riddles, as well). This is pretty essential to Old English poetics (and I can recommend some great formulaic theory readings for our hardcore readers).

Another-another thing to note: this riddle appears to have a missing half-line. Did the poet just get bored and lose the will to live? Is this some sort of crazy otherwise-unheard-of metrical pattern or device? Notice that lines 1 and 3 both alliterate on “w,” so there’s potential linking going on here. It seems likely, though, that the scribe writing this poem down lost track of a half-line. There is some damage to the manuscript (blotting), but it appears to affect the following line more than this one. At least, Williamson doesn’t attribute the gap to damage, saying only: “Though single half-lines are known to exist in Old English poetry […], the sense of the riddle seems to demand something more here” (p. 185).

Finally, I should nod to the comments about the final line in this riddle’s translation post. Although the reference to ceol (boat) works nicely if this object is imagined as being transported by ship (along with its great-big-happy-family of other jugs/amphorae/casks), commenter-Conan pointed out the easy mix-up that might occur with a similar word: ceole (throat). The grammar certainly seems to point to the first and we should note that these words likely sounded a bit different because ceol has a long diphthong and ceole a short one. But still, given that we’re looking at a situation that involves drinking (and therefore throats), I find that mix-up rather charming. But maybe it’s just that I’m thirsty…

Good-bye for now, readers. I think there’s an amphora at my local pub that’s calling my name.

References and Suggested Reading:

Glorie, F., ed. Variae Collectiones Aenigmatum Merovingicae Aetatis. Corpus Christianorum Series Latina, vol. 133-133A. Turnhout: Brepols, 1968 [you’ll find an edition and translation of Aldhelm’s Latin enigmata in here].

Williamson, Craig, ed. The Old English Riddles of The Exeter Book. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1977.

Tags: anglo saxon exeter book riddles old english solutions riddle 18

Related Posts:

Exeter Riddle 18