Exeter Riddle 57

MEGANCAVELL

Date: Thu 12 Jan 2017Matching Commentaries: Commentary for Exeter Riddle 57

Today’s translation post is by Michael J. Warren. He has just completed his PhD on birds in medieval English poetry at Royal Holloway, where he is now a visiting lecturer. His new projects continue to focus on animal studies and ecocritical approaches to the natural world. Check out Michael’s blog, The Compleat Birder, here.

Ðeos lyft byreð lytle wihte

ofer beorghleoþa. Þa sind blace swiþe,

swearte salopade. Sanges rope

heapum ferað, hlude cirmað,

tredað bearonæssas, hwilum burgsalo

niþþa bearna. Nemnað hy sylfe.

The air bears little creatures

over the hillsides. They are very black,

swarthy, dark-coated. Bountiful of song

they journey in groups, cry loudly,

tread the woody headlands, sometimes the town-dwellings

of the sons of men. They name themselves.

Notes:

There is an interactive Riddle 57 activity available here.

This riddle appears on folios 114r-114v of The Exeter Book.

The above Old English text is based on this edition: Elliott van Kirk Dobbie and George Philip Krapp, eds, The Exeter Book, Anglo-Saxon Poetic Records 3 (New York: Columbia University Press, 1936), page 209.

Note that this edition numbers the text Riddle 55: Craig Williamson, ed., The Old English Riddles of the Exeter Book (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1977), page 101.

Tags: anglo saxon exeter book riddles old english solutions riddle 57

Related Posts:

Response to Exeter Riddle 39

Commentary for Exeter Riddle 55

Commentary for Exeter Riddle 57

Commentary for Exeter Riddle 51

MEGANCAVELL

Date: Thu 05 Jan 2017Matching Riddle: Exeter Riddle 51

This post is once again by Britt Mize from Texas A&M University. Take it away, Britt!

Riddles, as a type of wisdom poetry, ask us to learn something by viewing ordinary things in extraordinary ways. When I teach about the Exeter Book riddles, sometimes I turn a chair upside-down on the floor. Then I ask the students to write one sentence describing its “chair-ness” in some way that is made possible only by looking at it from an unusual point of view.

Like this classroom exercise, Old English riddles are a game of perspective manipulation, and this manipulation of viewpoint is often a source of their obscurity. Readers must reverse-engineer the text, using the details that are provided and trying different ways of fitting them together, until they finally catch sight of what the writer has described in a defamiliarizing manner.

Riddle 51 is usually a stumper for people now when they first encounter it. This may have something to do with changes in writing technology (I am typing this on a laptop, not handwriting it with a pen, and even if I were, I wouldn’t be dipping mine in an inkwell). But I think it is mainly because this riddle’s manipulation of perspective involves the additional trick of violating scale. We’ve all seen the photographers’ gimmick of zooming in on something normal, and further and further in, until it becomes bizarre and unrecognizable. This riddle starts out “zoomed in” in exactly that way, and in order to solve it, we must “zoom out” with our mind’s eye and realize that the thing described is connected to the rest of a human body.

After my students make a few guesses, I ask them—the dwindling number of them who are taking notes on paper!—to look down at what they’re doing themselves, right at that very moment. At that point, someone always blurts out the solution: a pen and the three fingers guiding it. The creator of this riddle gives us an extreme close-up of a hand moving a quill tip across the writing surface, and back and forth from inkwell to page, as a scribe (the winnende wiga, “striving warrior”) writes out the text of what is probably imagined to be an expensively decorated or bound gospel manuscript, because such adornments would be most typically given to that kind of book.

Photo (by Urban) of some rather creepy, quill-wielding monk mannequins in the Museum of Bayeux from Wikimedia Commons (license CC BY-SA 3.0)

There are two metaphors I’d like to focus on in this riddle.

The more minor one is the “striving warrior” description near the end. This phrase usually provokes a few chuckles in a classroom setting because it seems overblown, if not self-aggrandizing, when used by a monkish writer to describe a person like himself. Similar remarks could be made about many language choices in the Exeter Book riddles, and maybe people a thousand years ago thought it was funny too. But the representation of writing as a kind of combat might also tell us something about how difficult the activity of manual text-copying is, not only in its bodily labor (which does become grueling after as little as a couple of hours: try it and see), but also in the concentration and perseverance that must be maintained to carry out the task with accuracy. Or it may be that a monk writing a holy text could quite seriously see himself as engaged in spiritual warfare against the powers of darkness and not find the martial language high-falutin at all.

The other, more interesting metaphorical pattern in this riddle imagines the act of writing as a journey or expedition—the verb siþian means to go on one of these—by something that leaves tracks behind. The way the fingers and pen are spoken of here defamiliarizes the writer’s hand by making it seem zoological, and the repeated insistence that the object described is somehow both singular and fourfold will probably encourage a reader to think of some sort of quadruped. The animal associations are continued, and the solution further estranged from ordinary viewpoints on a person’s hand, by the comparison with birds, and then by the surprise in the next line that this/these “wondrous creatures” can move deftly in liquid as well as upon the earth and through the air.

I have always loved the image of dark ink on a pale page as tracks across the ground (lastas and swaþu are words for the prints or trail that a person or animal leaves behind). The nuances of this metaphor say something about reading, too, not just about writing: unless somebody comes along later who can understand and follow these traces, they mean nothing. The implication is that a reader, just like a hunter or tracker, must carefully observe and interpret the signs he or she finds, endeavoring to stay with them, going where they lead in pursuit of a goal.

Photo (by David Castor) of rabbit tracks from Wikimedia Commons

The poet of Riddle 51 and I are not the only ones who have enjoyed contemplating this image, either. At least one 9th-century English prose writer liked it too, because the same metaphor lies behind a famous statement found in the preface to the Old English Pastoral Care. The preface is attributed to King Alfred of Wessex (r. 871–899), and here he, or whoever wrote on his behalf, contemplates the monastic libraries in his kingdom, full of Latin books that he says no one can read anymore. The writer grieves the present, illiterate generation’s terrible loss of earlier generations’ learning and intellectual labor:

Ure ieldran . . . lufodon wisdom, ond ðurh ðone hie begeaton welan ond us læfdon. Her mon mæg giet gesion hiora swæð, ac we him ne cunnon æfterspyrigean. Ond forðæm we habbað nu ægðer forlæten ge ðone welan ge ðone wisdom, forðæmðe we noldon to ðæm spore mid ure mode onlutan. (Sweet, vol. 1, page 5)

(Our predecessors . . . loved wisdom, and through it they gained prosperity and left it to us. One can still see their track here, but we do not know how to follow after them. And for that reason we have now lost both the prosperity and the wisdom: because we would not bend down to the track with our mind.)

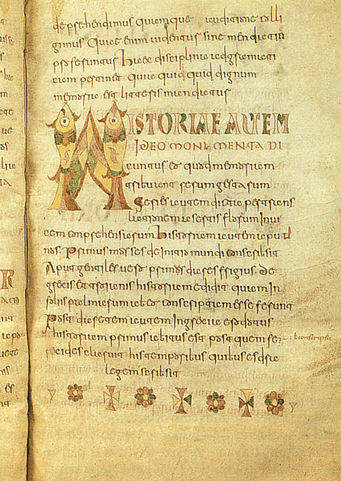

King Alfred’s West Saxon Version of Gregory the Great’s Pastoral Care in MS Hatton 20 (fol. 001r) from the Bodleian Library, University of Oxford

A modern poet, the Welsh priest R. S. Thomas (1913–2000), also returned more than once to the image of writing on a page as a track or path that something left behind its movement. In his 1961 poem “The Maker,” Thomas describes a poet preparing to create. After taking “blank paper,” the poet

drilled his thoughts to the slow beat

Of the blood’s drum; and there it formed

On the white surface and went marching

Onward through time, while the spent cities

And dry hearts smoked in its wake.

(Thomas, page 42)

The path here is one of military destruction, and it’s all too legible. In a later poem, “The Word” (1975), Thomas comes back again to the metaphor of writing as a track, this time in a way somewhat more similar to Riddle 51:

A pen appeared, and the god said:

“Write what it is to be

man.” And my hand hovered

long over the bare page,

until there, like footprints

of the lost traveller, letters

took shape on the page’s

blankness, and I spelled out

the word “lonely.” And my hand moved

to erase it; but the voices

of all those waiting at life’s

window cried out loud: “It is true.”

(Thomas, page 86)

R. S. Thomas’s “footprints of the lost traveller” resonate sympathetically with the disorientation lamented by the writer of the Pastoral Care preface. But there is still an important difference, and it’s one of perspective, which brings us back to the game that the riddles so often play.

For writers in the Old English tradition, the message of a text doesn’t just sit, as “content,” inside the block of writing that is present before the reader like a container, the way we tend to think of it. Instead, the message moves along the writing, or out in front of it (imagine a cursor on a computer screen that keeps going steadily forward), such that the inattentive or uncommitted reader is in danger of being left behind. This has to do with the fact that a thousand years ago writing was normally read aloud to listeners: receiving a text’s meaning was usually a time-bound, unidirectional event, like watching a movie is for us, that made it hard for audiences to go back and re-process the language as we can so easily do now when we privately read books or other textual media that we can freely manipulate. This condition of reception made for a different concept of “where” meaning is, in relation to its written manifestation, and what one must do to access it.

The important point here is that in an early English cultural context, writing suggests a message, a target of pursuit, that is always receding from the reader, a follower who must search for its signs and grasp at it. It must be actively kept up with.

This sense of distance and active pursuit is inherent in following an organic track along the ground. It can be seen, too, in language like that used in Beowulf, when Grendel’s severed arm, torn off at Heorot, is said to last weardian “guard his trail” (line 971b). The phrase simply indicates, in poetic language, that the limb is left behind when Grendel flees; but it does so by invoking the trail extending forward from the arm, a sort of dotted line connecting that dismembered body part with the target of pursuit, Grendel himself. Such a trail may be followed successfully, or may get lost in the faintness or unintelligibility of its signs. The realistic difficulty of tracking one’s prey or one’s fore-goer is captured well by the image, and we need to apply this sense to the metaphor of written language as a track, too.

In his poems cited above, R. S. Thomas always assumes of written tracks that observers can read them, if they wish. In “The Word,” they represent knowledge based on common experience, available to all and lost only if the many voices that affirm it are stifled; in “The Maker,” the written “wake” signals only a poem’s continuing ability to threaten its present readers like an army on a scorched-earth campaign. In both of Thomas’s poems the meaning, the “where” of the message, moves toward readers who may or may not wish to know it.

In contrast, the written traces that interested Old English writers are signs left behind by a message, by wisdom, that elusively moves away from readers and must be followed with great effort. The writer of the Pastoral Care’s preface worries that the trail is cold, that the learned predecessors are too far out of range to follow anymore.

It seems likely to me that the same implicit danger underlies Riddle 51’s controlling metaphor. The holy book whose copying this little Old English poem describes is a materially precious object, adorned with gold leaf. But in order for its value to transcend its material splendor, it must be read—and reading isn’t easy, least of all in Latin in 9th- or 10th-century Britain. Does Riddle 51’s (mock-)heroic tone, its sense of the monk-copyist’s triumphant skill, constitute a challenge to its readers or hearers not to let the wisdom of books get away? That challenging posture would certainly be appropriate to the genre of the riddle. So would a hint that the wisdom of books, like the solutions to riddles, must be sought with diligence, alertness to all possibilities, and readiness to see things from a new, unfamiliar perspective.

References:

Fulk, R. D., Robert E. Bjork, and John D. Niles, eds. Klaeber’s Beowulf and The Fight at Finnsburh. 4th edition. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2008.

Sweet, Henry, ed. King Alfred’s West-Saxon Version of Gregory’s Pastoral Care. 2 vols, Early English Text Society, old series 45 and 50. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1871; reprint, Millwood, NY: Kraus, 1978.

Thomas, R. S. The Poems of R. S. Thomas. Fayetteville: University of Arkansas Press, 1985.

Tags: anglo saxon exeter book riddles old english solutions riddle 51 britt mize

Related Posts:

Commentary for Exeter Riddle 43

Commentary for Exeter Riddle 57

Exeter Riddle 51