Exeter Riddles 75 and 76

VICTORIASYMONS

Date: Sun 18 Mar 2018Matching Commentaries: Commentary for Exeter Riddles 75 and 76

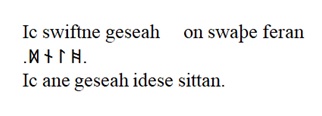

It’s another two-for-one this week! Most editors treat the first two lines as one riddle, and the third as a seperate riddle. Krapp and Dobbie are among them. Others, including Craig Williamson, edit this as a single poem. Also there are runes, so scroll down for a screenshot if you can't see them. Enjoy…

Ic swiftne geseah on swaþe feran

.ᛞ ᚾ ᛚ ᚻ.

[Riddle 76] Ic ane geseah idese sittan.

I saw a swift one travel on the way

.d n l h.

[Riddle 76] I saw a woman sit alone.

Notes:

This riddle appears on folio 127r of The Exeter Book.

The above Old English text is based on this edition: Elliott van Kirk Dobbie and George Philip Krapp, eds, The Exeter Book, Anglo-Saxon Poetic Records 3 (New York: Columbia University Press, 1936), page 234.

Note that this edition numbers the text Riddle 73: Craig Williamson, ed., The Old English Riddles of the Exeter Book (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1977), page 110.

Screen shot for the runes:

Tags: anglo saxon exeter book riddles old english solutions riddle 75 riddle 76

Related Posts:

Commentary for Exeter Riddles 68 and 69

Commentary for Exeter Riddles 75 and 76

Exeter Riddle 19

Commentary for Exeter Riddles 75 and 76

VICTORIASYMONS

Date: Mon 26 Mar 2018Matching Riddle: Exeter Riddles 75 and 76

Here’s a riddle for you: what do a dog, Jesus, and someone taking a pee all have in common? Answer: they’re all possible solutions for this week’s riddle. Or riddles. Yes, there’s quite a bit of mystery about Riddle 75 and/or Riddle 76, and the mystery starts with how many poems it or they actually is. Or are.

For reasons that will become clear below, I’m going to set the runes aside for a moment and focus on the two longer lines of poetry. The way they’re written in the manuscript strongly suggests that they’re two separate texts – each begins with capitalisation and on a new line, and closes with the kind of punctuation flourish normally reserved for endings. This is how a lot of editors, including Krapp and Dobbie, treat them. The problem is… there isn’t much there. These might be the opening lines of two longer riddles, but if so the scribe forgot to include the rest. Other editors have preferred to combine these two lines into a single text. This has the advantage of providing a little more bulk to work with, and nods to the structural similarities between the lines. In fact, there’s a sort of chiasmus – a balancing of two parallel clauses – in the contrast between the subject of the first line moving swiftly and the subject of the second line sitting alone. My feeling is that these two riddles are, in fact, a single text even if that’s not how they’re presented in the manuscript.

However we choose to edit the poem/s, one thing we can be confident about is that the runes are later additions. You see, when we find runes in the Exeter Book riddles they’re usually integrated into the metre, meaning that they (or rather, the words they signify) carry alliteration. The first rune in Riddle 19, for example, is ᛋ (line 1b), whose name sigel picks up the s- alliteration from the preceding half line.

But that’s not what happens here. These runes are just hanging out on the end of the first line, with not the slightest regard for alliteration or metrical stress or any of the things that make Old English poetry poetic. So what are they doing there?

The answer is that these runes have been interpolated – i.e. moved – from the margins into the text proper. This happens when a scribe is copying from one manuscript to another and mistakes a note in the margin for a continuation of the line. We see another of this kind of mistake in Riddle 36, and Andy Orchard argues it’s also the source of Riddle 23’s opening line (page 290). In both cases, these stray words were originally written into the margins of earlier copies of the poems, to provide cryptic clues for the riddles’ solutions.

Now, if you’re the sort of person who gets excited by manuscript-y stuff (aren’t we all?), this is actually pretty cool. Today, all but one of the Old English riddles comes to us from the Exeter Book. Everything we think we know about these riddles – that they were written without solutions, for example – is based on this one manuscript. But what we get here is a glimpse of the earlier manuscript from which th Exeter Book itself was copied. Preserved in this odd mish-mash of a poem is the relic of what that lost manuscript looked like. It’s the manuscript equivalent of finding dino DNA preserved in amber.

Sort of.

Photo credit: Brocken Inaglory, via Wikimedia Commons (licence: GNU Free Documentation Licence).

Once we’ve finished geeking out about palaeography, though, it’s time to get down to the real business: solving this thing. As you can see, there isn’t a great deal to go on. Taking only the poetic lines, we have either two riddles describing one thing moving quickly, and one thing sitting alone. Or we have one riddle describing both those things in tandem. No wonder someone thought it might be a good idea to include a little runic hint to help us along. What wise clue did our medieval runester grace us with?

Dnlh.

No, that’s not an Old English sneeze. That’s what the runes say. Dnlh.

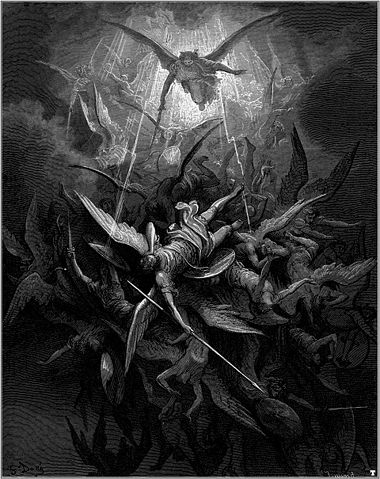

It may come as no surprise that “dnlh” isn’t a word, not in Old English nor in modern. But there are a couple of ways it might become a word, with some creative thinking and a loose approach to spelling. Reverse the letter order and add in some much-needed vowels and we might get hælend (lord). This solution was originally proposed by W. S. Mackie, who argued that the first line is a standalone riddle depicting Christ “as a hunter in pursuit of sin” (page 77). Playing around with letter order and vowels are two fairly common gambits in medieval cryptography – they’re used in Riddle 19 and Riddle 23 (reversed letters), or Riddle 36 (changed vowels). That’s solution one.

Solution one. Image from Wikimedia Commons (Public Domain).

But there’s actually a way of finding some vowels without adding anything to the runes at all. When written in manuscripts, runic ᛚ (l) often ends up looking similar to runic ᚢ (u). And if there’s one thing we can say for sure about the Exeter Book scribe, it’s that he or she isn’t particularly good at writing runes consistently. Changing the “l” for a “u” and reversing the letter order gives us hund (hound). So the riddle may be as simple as that: a poem about a dog running really fast, to which someone’s helpfully added the word dog so that we know it’s definitely about a dog. This is solution two, and it’s a popular one (Bitterli, pages 105-10).

Solution two.

Image credit: Sheila Sund via Wikimedia Commons (licence: Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic).

Solution three comes courtesy of Craig Williamson, who opines that “the pursuit of sin has no place in this riddle” (page 353), and that the word signified by our runic quartet is actually hland (urine). Williamson’s reading supports combining the two lines into one poem; the contrast between them speaks to the contrast between male and female peeing… postures.

Solution three: not pictured. I’ll leave it to your imagination. Image credit: Tuxyso via Wikimedia Commons (licence: Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0).

Which one is the correct solution? It’s honestly impossible to know. We don’t even know for sure that the runes have anything to do with conveying a solution. But that ambiguity is pretty fun. In fact, I’d argue one of the best things about this poem (or these poems) is how evocative it is. These two little lines may represent the shortest of the Exeter Book riddles, but they’ve provoked page upon page of critical commentary encompassing a truly eclectic range of solutions and creative readings. And thus we get from Jesus Christ to peeing postures, via one happy hound!

References and Suggested Reading

Bitterli, Dieter. Say What I am Called: The Old English Riddles of the Exeter Book and the Anglo-Latin Riddle Tradition. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2009.

Mackie, W. S. “Notes on the Text of the Exeter Book.” Modern Language Review, vol. 28 (1933), pages 75-78.

Orchard, Andy. “Enigma Variations: The Anglo-Saxon Riddle-tradition.” In Latin Learning and English Lore: Studies in Anglo-Saxon Literature for Michael Lapidge. Edited by Katherine O’Brien O’Keeffe and Andy Orchard (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2005), pages 284-304.

Williamson, Craig, ed. The Old English Riddles of The Exeter Book. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1977.

Tags: anglo saxon exeter book riddles old english solutions riddle 75 riddle 76

Related Posts:

Commentary for Exeter Riddle 19

Commentary for Exeter Riddle 23

Commentary for Exeter Riddle 36