Commentary for Bern Riddle 42: De glacie

NEVILLEMOGFORD

Date: Mon 01 Mar 2021Matching Riddle: Bern Riddle 42: De glacie

I like to think that the Bern Riddles are twice as ice as other riddle collections—because they have not one, but two riddles about the frozen stuff! (That is, if Riddle 38 is actually about ice at all!)

“Ice and water. Photograph (by Sharon Mollerus) from Wikimedia Commons (licence: CC BY 2.0)”

Our riddle starts off by employing the softness/hardness trope that found in so many of the Bern Riddles, from the sexy pottery in Riddle 1 all the way to the chaste rose in Riddle 53. I am not sure exactly how to explain the “many” (multos) in line 2, but the idea of a thing that cannot be hardened and “makes many soft” sounds like a kind of sexual inuendo-in-reverse. The Early Middle Ages are often depicted in popular culture as a time of solemn religiosity and stern authority, but playful texts like these remind us that they had a lighter (and sexier) side too. I really do think that parts of these riddles are an early medieval version of “that’s what she said.”

Line 3 combines two common riddle tropes (“solving” and kissing) in a single line. The intention is to connect the act of reading riddles with the melting of ice—just as learned readers rejoice when a riddle has been “solved” (soluta), so the ice is “praised with dear kisses” when it has “dissolved” (soluta) into water. The “kisses” (oscula) are the human mouths that drink the water, presumably from Riddle 6’s cup (which also describes drinking as kissing). Line 4 then employs two more common riddling tropes, binding and touching, to describe how the ice can be unpleasantly cold to touch.

“Ice melting. Photograph (by Dingske) from Wikimedia Commons (licence: CC BY-SA 2.0)”

Lines 5 and 6 are very curious, and I am not entirely sure what they mean. They probably refer to the transition between states of liquidity and solidity, and the “stern creator” (rigidus auctor) could be describing the winter’s cold. However, the references to “beautiful” (pulchra) and “ugly” (turpis) forms are more cryptic. Ice can be terrifyingly ugly for travellers climbing through mountain passes or sailors steering through icebergs. It can also be beautiful in the way that it shimmers and reflects light. Likewise, water can be terrifyingly ugly during a sea storm or a flash flood, and it can be beautiful in its tranquillity. Incidentally, the beautiful/ugly motif also appears in one of my favourite riddles, No. 61, where it describes the stars in a similarly cryptic way.

For me at least, this riddle is a very cool mix of the familiar and the strange. It uses a patchwork of common tropes and motifs, but its workings are quite obscure at times. And that is exactly what you would expect from such a slippery riddle!

References and Suggested Reading:

Winterfeld, Paul. “Observationes criticalae.” Philologus vol. 53 (1899). Pages 289-95.

Tags: latin Bern Riddles

Related Posts:

Bern Riddle 39: De hedera

Bern Riddle 61: De umbra

Commentary for Bern Riddle 41: De vento

NEVILLEMOGFORD

Date: Mon 01 Mar 2021Matching Riddle: Bern Riddle 41: De vento

What kind of a riddle-creature is fast and strong, bites without a mouth, raises up the weak, and is more powerful than Hercules? The answer, my friend, is blowin' in the wind.

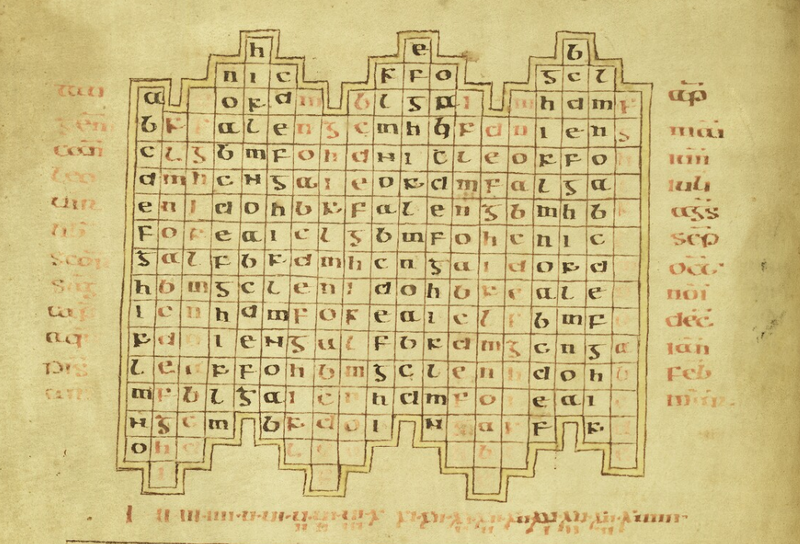

The wind was a popular topic in early medieval scientific works such as Isidore of Seville’s early 7th century De natura rerum and Bede’s early 8th century De natura rerum, both of which drew on a wide range of classical and late antique learning. These texts were often accompanied by diagrams of the twelve winds, such as the one below. The wind was also a popular subject for early medieval riddlers. Aldhelm of Malmesbury wrote a wind riddle (Aldhelm Riddle 2), which begins “no one can see me” (cernere me nulli possunt), before describing how it blows all around the countryside, shattering oaks. And the Exeter Book contains three back-to-back riddles (or one, depending on your perspective) about different kinds of wind—you can read Megan’s commentary on them here.

Our riddle stresses the wind’s awesome power using several common Bern themes and motifs. Line 1 employs the birth motif to frame the idea that the wind is fast and strong. And Line 2 describes the wind’s power to push down heavy things and lift things up in terms of raising up the weak and humbling the strong. This makes the riddle creature sound rather Christ-like, just as we found with the resurrected cup and grain in Riddles 6 and 12, as well as Riddle 22’s humble sheep. Finally, Lines 4 and 5 recall the multiple mouths of the previous riddle on the mousetrap, and the mention of biting recalls several earlier riddles (see my discussion of this trope in the commentary to Bern Riddle 37).

Line 6 explains that the wind is invisible but more powerful than any human, including some of the strongest men in history, such as “the Macedonian” (i.e. Alexander the Great), Liber (the Roman god of fertility and wine, often used interchangeably with Dionysius), and Hercules. The author cited these three based on a longstanding classical and medieval tradition of attributing a series of conquests of India to them. (Alexander did invade the Indus Valley basin in 326-5 BCE, but the others are entirely mythical.) For example, Pliny the Elder wrote in the 1st century CE that:

Haec est Macedonia, terrarum imperio potita quondam…haec etiam Indiae victrix per vestigia Liberi Patris atque Herculis vagata…

Such is Macedonia, which once won a world-wide, empire… and even roamed in the tracks of Father Liber and of Hercules and conquered India…

—Pliny, Natural History. Book 4, pages 146-7.

Similar associations can be found in a wide range of sources, from classical works by Ovid (The Metamorphoses, pages 180-1) and Seneca (Oedipus, pages 54-5) to the medieval travel works, The Letter of Alexander to Aristotle (Orchard, pages 240-1) and the Liber Monstrorum (Orchard, pages 290-3), that feature in the Nowell codex alongside Beowulf.

Like many other Bern Riddles, there is a lot of stuff going on in six short lines—they go far beyond the obvious statements about the wind being powerful yet invisible. Perhaps this riddle doesn’t exactly blow me away in the same way that some of the most creative riddles do, but I’m definitely still a big fan.

References and Suggested Reading:

“Liber Monstrorum” and “The Old English Letter from Alexander to Aristotle.” In Andy Orchard, Pride and Prodigies: Studies in the Monsters of the Beowulf-Manuscript. Woodbridge: D. S. Brewer, 1995. Pages 224-317.

Cesario, Marilina. “Knowledge of the weather in the Middle Ages: Libellus de disposicione totius anni futuri.” In Marilina Cesario and Hugh Magennis (eds.), Aspects of Knowledge. Preserving and Reinventing Traditions of Learning in the Middle Ages. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2018. Pages 53-78.

Ovid, Metamorphoses, Books 1-8. Translated by Frank Justus Miller. Revised by G. P. Goold. Loeb Classical Library 42. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1916.

Pliny the Elder. Natural History, Books 3-7. Edited and translated by H. Rackham. Loeb Classical Library 352. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1942.

Seneca the Younger. Oedipus. In Tragedies, Volume II: Oedipus. Agamemnon. Thyestes. Hercules on Oeta. Octavia. Edited and translated by John G. Fitch. Loeb Classical Library 78. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2018.

Winterfeld, Paul. “Observationes criticalae.” Philologus vol. 53 (1899). Pages 289-95.

Tags: latin Bern Riddles

Related Posts:

Commentary for Exeter Riddles 1-3

Bern Riddle 6: De calice

Bern Riddle 12: De grano

Bern Riddle 22: De ove

Bern Riddle 37: De pipere

Bern Riddle 40: De muscipula