Exeter Riddle 63

MEGANCAVELL

Date: Mon 29 May 2017Matching Commentaries: Commentary for Exeter Riddle 63

FYI, the manuscript is pretty damaged here, so the last few lines are impossible to reconstruct. Try to enjoy nonetheless!

Oft ic secga seledreame sceal

fægre onþeon, þonne ic eom forð boren

glæd mid golde, þær guman drincað.

Hwilum mec on cofan cysseð muþe

5 tillic esne, þær wit tu beoþ,

fæðme on folm[. . . . .]grum þyð,

wyrceð his willa[. . . . . .]ð l[. . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . .] fulre, þonne ic forð cyme

[. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .]

10 Ne mæg ic þy miþan, [. . . . . . . . . . .

. . . . . . . . . . . . . .]an on leohte

[. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .]

swylce eac bið sona

. .]r[.]te getacnad, hwæt me to [. . . .

15 . . . .]leas rinc, þa unc geryde wæs.

Often I must prosper fairly among the hall-joy

of men, when I am carried forth

shining with gold, where men drink.

Sometimes a capable servant kisses me on the mouth

5 in a chamber where we two are,

my bosom in his hand, presses me with fingers,

works his will . . .

. . . full, when I come forth

. . .

10 Nor can I conceal that . . .

. . . in the light

. . .

so too is it immediately . . .

indicated, what from me . . .

. . . less warrior, when it was pleasant for us two.

Notes:

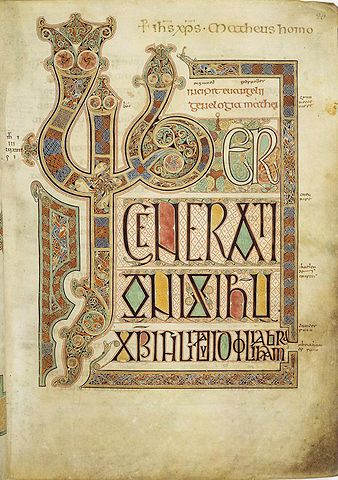

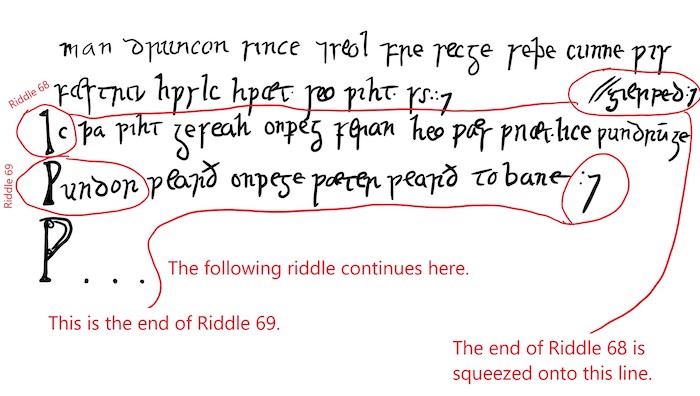

This riddle appears on folio 125r of The Exeter Book.

The above Old English text is based on this edition: Elliott van Kirk Dobbie and George Philip Krapp, eds, The Exeter Book, Anglo-Saxon Poetic Records 3 (New York: Columbia University Press, 1936), pages 229-30.

Note that this edition numbers the text Riddle 61: Craig Williamson, ed., The Old English Riddles of the Exeter Book (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1977), pages 104-5.

Tags: anglo saxon exeter book riddles old english solutions riddle 63

Related Posts:

Exeter Riddle 3

Exeter Riddle 23

Exeter Riddle 73

Commentary for Exeter Riddle 63

MEGANCAVELL

Date: Wed 07 Jun 2017Matching Riddle: Exeter Riddle 63

If Riddle 63 has anything to teach us, it’s that people with hot pokers SHOULD NOT BE ALLOWED NEAR MANUSCRIPTS! Sorry…got a bit shouty there. All those years of pent-up scholarly rage have to take their toll at some point. I’m fine now.

Ahem.

So, Riddle 63. This is the first of many very damaged riddles that we’re going to be working through from this point on. They’re damaged because – as you might have guessed – there’s a long, diagonal burn from where someone put a hot poker or fiery brand on the back of the Exeter Book.

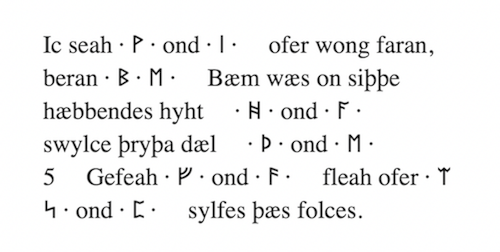

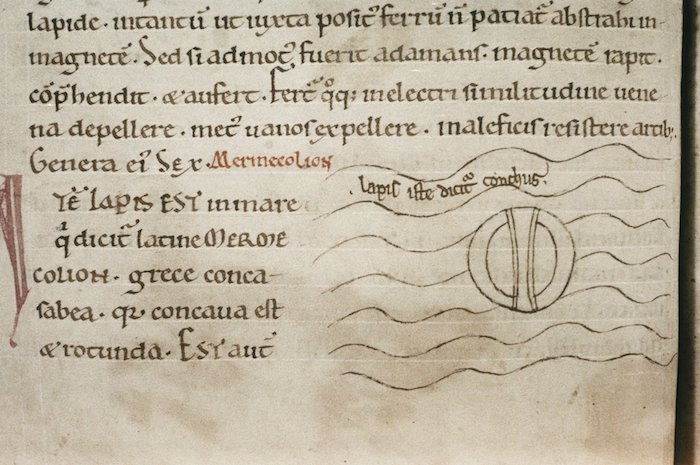

A photo of the damage to this page of the manuscript (folio 125r). I am *very* grateful to the manuscripts and archives team for providing this Exeter Cathedral Library photo (reproduced by courtesy of the Dean and Chapter of Exeter)

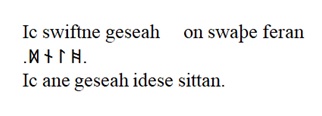

Even with the damage, we can still have a conversation about Riddle 63 because – thankfully – several of its opening lines are intact, and intriguing hints survive further on in the poem. We have enough information, for example, to have a convincing stab at the solution, which seems to be a glass beaker or perhaps glæs-fæt in Old English (though early solvers also suggested “flute” and “flask”).

Glass beakers are a fairly common find in early medieval graves, and there’s pretty good evidence for solving the riddle this way. Some of this evidence comes from within the poem: the references to a servant handling and kissing the object from line 4 onward suggest that it’s a drinking vessel. And the object’s statement Ne mæg ic þy miþan (Nor can I conceal that) in line 10a implies that it’s transparent.

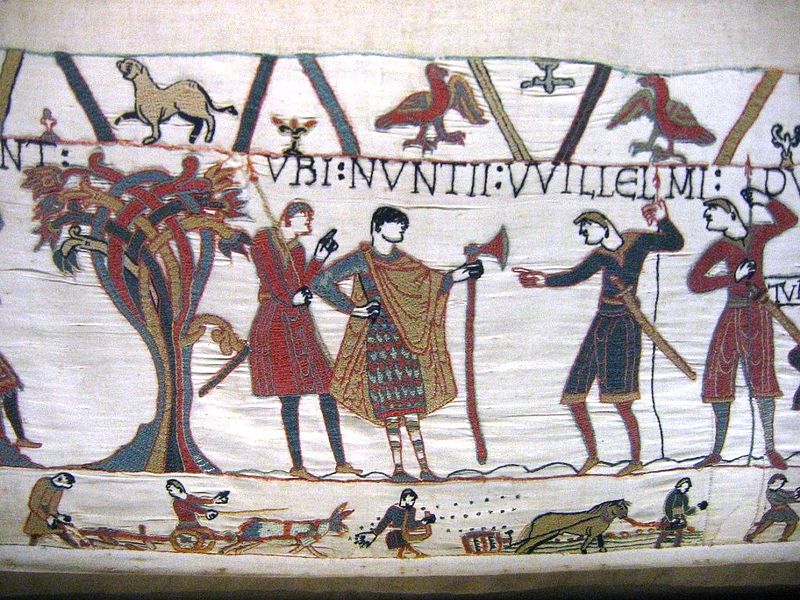

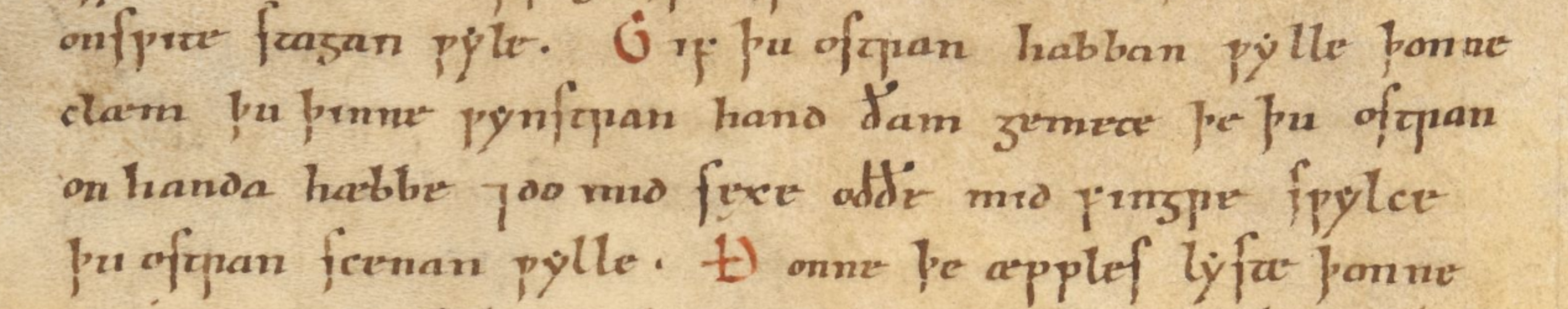

A claw beaker from Ringlemere Farm, Kent, via Wikimedia Commons (public domain). You can find out more about it here.

I suppose you could argue that the holes in flutes would make concealing anything difficult too, and of course kissing and pressing with fingers are entirely relevant for a musical instrument of that kind. But we also have evidence for reading Riddle 63 as glass beaker that comes from outside of the poem. There’s a really, really, really useful parallel in one of the Anglo-Latin riddles written by the 7th/8th-century abbot and bishop Aldhelm. His Enigma 80, Calix Vitreus (Glass Chalice) has a similar reference to grasping with fingers and kissing, you see:

Nempe uolunt plures collum constringere dextra

Et pulchre digitis lubricum comprendere corpus;

Sed mentes muto, dum labris oscula trado

Dulcia compressis impendens basia buccis,

Atque pedum gressus titubantes sterno ruina.

(Glorie, vol. 133, page 496, lines 5-9)

(Truly, many wish to squeeze my neck with their right hand and seize my beautifully sinuous body with their fingers; but I change their minds, while I deliver kisses to their lips, dispensing sweet kisses to puckered mouths, and yet I throw off the faltering steps of their feet in a fall.)

This is a deeply disturbing vision of a sexual encounter loaded with complicated and competing power dynamics. There’s a lot of kissing here, sure, but there’s also a hint of violence in that term constringere, which can mean “to embrace,” but also “to bind/constrict” (hence I’ve gone for “squeeze”). Fifty Shades of Græg, amirite?

And while it’s the drinkers who initially want to inflict this violence on the drinking vessel, the vessel ends up turning the tables, so to speak, when the drinkers become so intoxicated that they fall over. This leads Mercedes Salvador-Bello to discuss Aldhelm’s Latin riddle in the light of early medieval views on prostitution: she argues convincingly that the riddle imagines a prostitute bringing about the downfall of a man through a combination of sexual charms and excessive wine (page 371). She also suggests the poem might be alluding to the apocalyptic Whore of Babylon from the biblical Book of Revelation (see also Magennis, page 519). Heavy stuff.

I also think there’s a possible pun here in the verb muto (I change), which could easily be confused for the terribly rude noun muto (penis). I mean, it doesn’t work grammatically, but it might have caused an embarrassed titter nonetheless.

And this leads us back again to Riddle 63, which is equally euphemistic but with a very different tone (at least as far as we can tell!). There are certainly similarities between the Latin and Old English riddles – both involve what my mum used to call “kissy face, pressy bod” (otherwise known as “sex”). Riddle 63’s reference to the human in the riddle who wyrceð his willa (works his will) in line 7a should look familiar from Riddle 54 (line 6a). And þyð (presses) also appears in sexual contexts in Riddle 12 (line 8b), Riddle 21 (line 5b) and Riddle 62 (5a).

But what I quite like about this riddle is that the sexual act is clearly a mutually enjoyable one: þa unc geryde wæs (when it was pleasant for us two) (line 15b). Look at that glorious dual pronoun! Unc! “Us two”! This glass beaker is properly into it.

Still, there are some issues with class that muddy the waters a bit. Patrick Murphy reminds us that this riddle – like so many others – confuses the matter of who is serving whom; this speaker is “habitually compelled to serve men but also itself attended at times by a tillic esne ‘useful servant’” (page 205). While the one handling the glass beaker is imagined as a person from a lower status background, the beaker itself is glæd mid golde (shining with gold). This level of bling makes me wonder if Riddle 63’s glass beaker is – rather than a prostitute, like in Aldhelm’s Latin riddle – imagined as a high-status person having a fling with a servant in a private chamber. On a literal level, this gold could be metal ornamentation around the glass beaker (Salvador-Bello, page 372), but figuratively it might point to all those wondrous arm- and neck-rings that bedeck elite lords, ladies and retainers in heroic poetry.

I want to point to one final comparison before I close up shop for the day. A few weeks ago at a fascinating lecture about fear, Alice Jorgensen from Trinity College Dublin reminded me about a funny little reference in Blickling Homily 10, Þisses Middangeardes Ende Neah Is. This late 10th-century homily says that the dead will be forced to reveal their sins on Judgement Day:

biþ þonne se flæschoma ascyred swa glæs, ne mæg ðæs unrihtes beon awiht bedigled (Morris, pages 109/11)

(then the flesh will be as clear as glass, nor may its wrongs be at all concealed).

Isn’t this too perfect? The glassy flesh of sinners will no longer be able to conceal sins when the end of the world comes! Just like the glass of a beaker reveals what’s in it. Those sins – whether consensual sex between people of different social ranks, or the prostitute and drunken patron’s power struggle – are all going to be on display. A sobering note to end on, I know. (get it?)

References and Suggested Reading:

Glorie, F., ed. Variae Collectiones Aenigmatum Merovingicae Aetatis. Corpus Christianorum Series Latina, vol. 133-133A. Turnhout: Brepols, 1968.

Leahy, Kevin. Anglo-Saxon Crafts. Stroud: Tempus, 2003, esp. pages 106-7.

Magennis, Hugh. “The Cup as Symbol and Metaphor in Old English Literature.” Speculum, vol. 60 (1985), pages 517-36.

Morris, Richard, ed. The Blickling Homilies. Early English Text Society o.s. (original series) 58, 63, 73. London: Oxford University Press, 1874-80.

Murphy, Patrick J. Unriddling the Exeter Riddles. University Park, PA: Pennsylvania State University Press, 2011, pages 204-6.

Salvador-Bello, Mercedes. “The Sexual Riddle Type in Aldhelm’s Enigmata, the Exeter Book, and Early Medieval Latin.” Philological Quarterly, vol. 90 (2012), pages 357-85, esp. 371-2.

Stephens, Win. “The Bright Cup: Early Medieval Vessel Glass.” In The Material Culture of Daily Living in the Anglo-Saxon World. Edited by Maren Clegg Hyer and Gale R. Owen-Crocker. Exeter: University of Exeter Press, 2011 (repr. 2013 by Liverpool University Press), pages 275-92.

Tags: anglo saxon exeter book riddles old english solutions riddle 63 bibliography latin

Related Posts:

Commentary for Exeter Riddle 12

Commentary for Exeter Riddle 21

Commentary for Exeter Riddle 54

Commentary for Exeter Riddle 62