Aldhelm Riddle 47: Hirundo

ALEXANDRAREIDER

Date: Tue 15 Mar 2022Absque cibo plures degebam marcida menses,

Sed sopor et somnus ieiunia longa tulerunt;

Pallida purpureo dum glescunt gramine rura,

Garrula mox crepitat rubicundum carmina guttur.

Post teneros fetus et prolem gentis adultam

Sponte mea fugiens umbrosas quaero latebras;

Si vero quisquam pullorum lumina laedat,

Affero compertum medicans cataplasma salutis

Quaerens campestrem proprio de nomine florem.

I was living without food for several months, wasting away,

But slumber and sleep supported the long fasts;

When the pale countryside blazes with radiant plants,

My ruddy throat immediately twitters away in chattering songs.

After my young offspring and my kind’s offspring are grown,

I flee of my own will and seek shady refuges;

But if indeed someone should injure my chicks’ eyes,

I, as the doctor, provide a proven poultice for health,

Seeking a flower of the field of my own name.

Notes:

This edition is based on Rudolf Ehwald, ed. Aldhelmi Opera Omnia. Monumenta Germaniae Historica, Auctores Antiquissimi, 15. Berlin: Weidmann, 1919, pages 59-150. Available online here.

Tags: riddles latin Aldhelm

Commentary for Bern Riddle 47: De cochlea

NEVILLEMOGFORD

Date: Mon 01 Mar 2021Matching Riddle: Bern Riddle 47: De cochlea

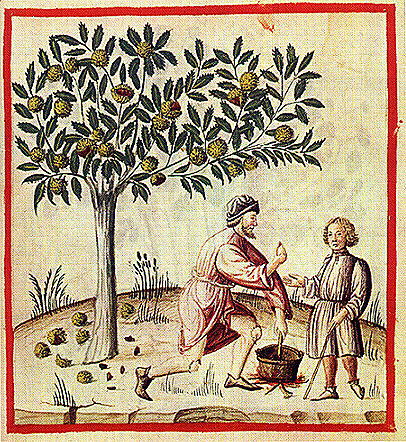

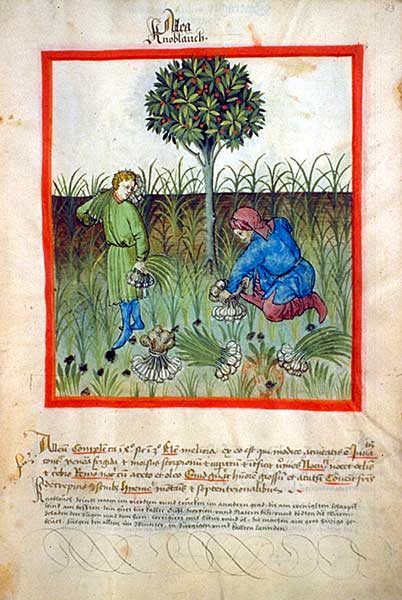

Although this riddle appears in manuscripts with the title De castanea (“About the chestnut”), it is probably more of a chestnot. In his 1968 edition of the riddles, Glorie amends it to De cochlea (“About the snail”), with some justification. For what it is worth, I agree with him—I think that it has been confused with Riddle 48, which really is about a chestnut (well, probably, anyway!). However, there are issues with both solutions. Don’t think that the Exeter Book Riddles are the only medieval riddles that need solving!

Line 1 tells us that the riddle creature is “born with hard skin” (aspera produci, Line 1), which can be applied to both snails and chestnuts, at least to a certain degree. But the reference to a “soft cloak” (lenis amictus) is a bit more problematic. The body of a snail is soft, but the noun amictus, which can mean cloak or clothing more generally, suggests an outer layer. At a push, the spiky, protective cupule of a chestnut could also be called soft. However, neither solution seems to fit particularly well.

The sonitus magnus (“great noise”) produced “from the belly” (de ventre) in Lines 3 and 4 is jokingly intended to sound like a rumbling tummy or flatulence, but it also provides the most evidence for the snail solution. Snails themselves do not make any great noise. (Although gastropods can produce tiny squeaks, grunts, and munching sounds, these are barely audible to the human ear.) The more likely explanation is that the author was referring to the shell of a marine snail, also known as a conch. Various kinds of shell can be modified to create a conch trumpet. When intacta (“intact”), the shell can be blown just like a horn; when corrupta (“damaged”), it cannot be played. This reminds me somewhat of the horn of Exeter Riddle 14, which calls warriors to hilde (“to battle”) and to wine (“to their wine”). Alternatively, the “great noise” could refer to the resonance of the shell when placed against the ear, which gives rise to the myth that one can hear the sea when doing so. I should also point out that Thomas Klein has taken Riddle 47 as evidence of southern European origin (Klein, page 404). There are plenty of marine gastropods in British waters, and whelk shells can grow to a moderate size. I don’t know if they are large enough for conch-blowing, but if you listen, you just might be able to hear the sea in them.

The final two lines could apply to either the chestnut or the snail—the idea seems to be that the riddle creature is enjoyed by humans when its outer layer is removed, presumably to be eaten. They also have sexual connotations—you cannot really call it innuendo, since innuendo is usually oblique, whereas the riddle is very explicit that this creature cannot truly be loved unless it is naked (nuda) and unclothed. In doing so, it recalls the table of Riddle 5 and the parchment of Riddle 24, both of which are also stripped of clothing.

If this riddle is about snails, as I believe it is, then it certainly manages to avoid all the clichés—it compares favourably with the 5th century riddle-writer, Symphosius’ riddle on the same subject, which begins with the hackneyed lines, Porto domum mecum (I carry my own home…”). You could say that Bern Riddle 47 is pretty spe-shell!

References and Suggested Reading:

Klein, Thomas. “Pater Occultus: The Latin Bern Riddles and Their Place in Early Medieval Riddling.” Neophilologus 103 (2019), 339-417, page 415.

Tags: latin Bern Riddles

Related Posts:

Exeter Riddle 14

Bern Riddle 5: De mensa

Bern Riddle 24: De membrana

Bern Riddle 48: De castanea