Date: Wed 17 Feb 2021

Matching Commentaries:

Commentary for Exeter Riddle 95

Riddle 95’s translation is by Brett Roscoe of The King’s University, Alberta. Thanks for taking on the very last Exeter riddle, Brett!

Original text:

Ic eom indryhten ond eorlum cuð,

ond reste oft; ricum ond heanum,

folcum gefræge fere (1) wide,

ond me fremdes (2) ær freondum stondeð (3)

5 hiþendra hyht, gif ic habban sceal

blæd in burgum oþþe beorhtne god. (4)

Nu snottre men swiþast lufiaþ

midwist mine; ic monigum sceal

wisdom cyþan; no þær word sprecað

10 ænig ofer eorðan. Þeah nu ælda bearn

londbuendra lastas mine

swiþe secað, ic swaþe hwilum

mine bemiþe monna gehwylcum.

Translation:

I am noble and known to men of rank,

and I rest often; to rich and poor,

to people far and wide I am known,

and to me, formerly estranged from friends, remains

5 the hope of plunderers, if I should have

honour in the cities or bright wealth.

Now wise men above all cherish

my company; to many I must

tell of wisdom, where they speak not a word,

10 nothing throughout the earth. Though now the sons of men,

sons of land-dwellers, eagerly seek

my tracks, I sometimes hide

my trail from all of them.

Click to show riddle solution?

Book, Quill Pen, Riddle (Book), Wandering Singer, Prostitute, Moon

Notes: This riddle appears on folio 130v of The Exeter Book.

The above Old English text is based on this edition: Elliott van Kirk Dobbie and George Philip Krapp, eds, The Exeter Book, Anglo-Saxon Poetic Records 3 (New York: Columbia University Press, 1936), page 243.

Note that this edition numbers the text Riddle 91: Craig Williamson, ed., The Old English Riddles of the Exeter Book (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1977), pages 120-1.

Translation Notes:

- (1) The manuscript reads fereð. Williamson takes hiþendra hyht as the subject of fereð wide, translating, “The plunderers’ joy (gold) travels far, and, once estranged from friends, stands on me (shines from me?), if I should have glory in the cities or bright wealth” (pp. 398-99). Murphy translates, “The plunderer’s joy travels widely and stands as a friend to me, who was a stranger’s before, if I am to have success in the cities or possess the bright Lord.” See Patrick J. Murphy’s Unriddling the Exeter Riddles (University Park, PA: Pennsylvania State University Press, 2011), page 87.

- (2) The manuscript fremdes does not make sense because there is no genitive noun in the sentence. I follow Williamson’s suggestion in reading this as fremde (pages 399-400).

- (3) Stondeð literally means “stands,” so a literal translation would be “stands on me.” But the meaning may be understood as “remains (to me)” or “falls to my lot” (Williamson, page 400).

- (4) Here I have followed the suggestion of numerous editors in assuming that beorthne should be beorhte, an adjective describing god, which here means “goods” or “wealth.” See Williamson, page 401.

Tags:

anglo saxon

exeter book

riddles

old english

solutions

brett roscoe

riddle 95

Related Posts:

Exeter Riddle 26

Exeter Riddle 29

Exeter Riddle 83

Commentary for Exeter Riddle 92

MEGANCAVELL

Date: Thu 03 Dec 2020Matching Riddle: Exeter Riddle 92

Judy Kendall, Reader in English and Creative Writing at Salford University, has provided Riddle 92’s commentary, including a new solution to the riddle. Take it away, Judy!

There have been various solutions to this riddle. While a number keep to the theme of beech (“beech,” “beech-wood shield,” “beech battering ram”), we also have “book,” and Ferdinand Holthausen’s initial suggestion of “ash.” Craig Williamson records that A. J. Wyatt read it as the Old English bōc, “beech with its several uses, and book,” and the tendency since then has been for riddle solvers to select “beech” rather than another kind of tree, linking it to “book” as Wyatt does (page 391). This is largely because of the record of pigs enjoying beechmast in line 107 of Riddle 40 where a boar is observed “rooting away” in a beech-wood. So, the argument goes, in line 1 of Riddle 92, “brown” or “red-brown” must indicate pig while “boast” clearly alludes to the beechmast that it is snuffling up.

However, there are other brown or red animals that also feast on forest tree produce. Red squirrels come to mind. Here’s a really nice picture of one:

Photo (by 4028mdk09) from Wikimedia Commons (licence CC BY-SA-3.0).

Squirrels also eat hazelnuts and acorns. In fact the Old English for squirrel is ācweorna, not that dissimilar to áccærn or áccorn, the word for nuts or “mast” of both beech and oak (ac), so there could perhaps be an intentional allusion to a squirrel gorging on a feast of nuts. After all ácweorran means "to guzzle or glut," and here is a red squirrel about to guzzle an acorn (not that we need proof that they love nuts!).

Photo (by Klearchos Kapoutsis) from Wikimedia Commons (licence CC BY 2.0).

Still, we shouldn’t forget the pigs. So here is an 1894 painting of pigs rooting for beechmast:

From William Sharp’s Fair Women in Painting and Poetry (1894, page 181), via Wikimedia Commons (no known copyright restrictions).

And an excellent little film of a whole row of pigs cracking and eating hazelnuts – spot the red-brown ones:

So boast or beot could refer to the red coat of a squirrel or the brown skin of a pig. However, it could also allude to a red-brown carpet of beechnuts, or indeed, acorns. See the glorious russet colours they create here:

Wet beech bark: Trees alongside the Gloucestershire Way in the Forest of Dean. Photo (by Jonathan Billinger) from Wikimedia Commons (licence CC BY-SA 2.0).

Who wouldn’t want to boast of that? Here’s an acorn carpet too:

White oak (Quercus alba) acorns - one prolific tree can nearly cover the ground in a good year. Duke Forest Korstian Division, Durham North Carolina. Photo (by Dcrjsr) from Wikimedia Commons (licence CC BY 3.0). (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0)

When Williamson dissects Wyatt’s argument for "beech," he stresses the way the riddle seems to turn on the homonymic uses of the word bōc – that is, as referring to both “book” and “beech” (page 391). Strictly speaking, the etymological connection between the two may be in doubt, but it is feasible that Old English speakers would have seen and heard them as linked, and, as Williamson argues, beech is also connected to books in the form of writing on beech-bark.

However, should we be content with beech? We have already mentioned the nuts of both the hazel and the oak, and certainly, the oak’s magnificent broad crown and reddish-brown or golden autumn leaves fit the celebratory description of many of the lines, while the hazel, too, similarly glorious in autumn, would also provide a possible match. So I would like to suggest "oak" as a new solution to this riddle, as well as urging you to consider the possibility of "hazel" too.

To this end, I will now work through the riddle as if the answer was “beech” and then recast it with an oak in tow, plus a few references to hazel thrown in along the way. Let's see where we get to.

One strong impression I had when approaching this riddle as a poet-translator is its continuous untiring celebration of a tree’s transformative journey in every line. Right from the word “go,” even down in the mud as pig or squirrel fodder, we have beot or “boast.” We have already noted how this could fit the description of an oak or hazel in autumn, and indeed it does also fit the image of a large handsome beech, resplendent in glorious gleaming yellow or orange autumn foliage, surrounded by a carpet of rich russet-coloured beechnuts. Perhaps this riddle is less of a beech teaser and more of a beech feaster:

Watercolour painting by Myles Birket Foster from Wikimedia Commons (Public Domain).

More celebratory references occur in the next line which describes other, wider forms of fine or noble nourishment. A sense of exultation gleams through line 3’s focus on forms of pleasure, possibly in book, or beech-bark, form, and we can see why such a bark might be chosen and celebrated in this picture of beautiful grey smooth beech:

Photo of beech bark (by Jonathan Billinger) from Wikimedia Commons (licence CC BY-SA 2.0).

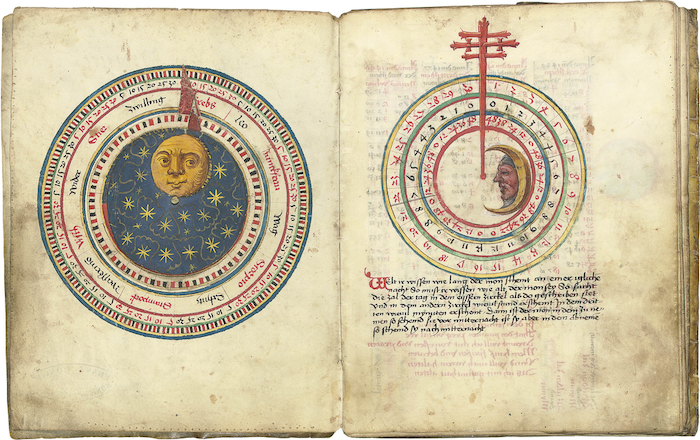

Note, however, that the tree’s transformation into book occurs halfway through the riddle. It is therefore just a stage on the tree’s journey, not its final destination. This throws doubt on the suggestion that “book” constitutes the answer to the riddle. Instead, it would seem that “book” is just a part of the process, as the tree, and riddle, works towards its solution.

Indeed, does an assessment of which tree is intended really help us solve the riddle? My first thought when looking at this riddle was that it is far too obviously about a tree to be actually referring, in a riddle-like way, to a tree. We riddle, surely, to confuse. If the solution is a kind of the tree, then the usual translation of the second half of line 1 as “tree in the forest” seems a bit much. Surely that kind of obvious hint should be saved till later – till the last line perhaps (a line of course to which we no longer have much access).

Observations like these are partly why I have allowed myself to translate beam as “a bough” rather than “tree,” making it more riddle-like, as well of course as facilitating alliteration.

Frederick Tupper, Jr. describes this riddle a series of kennings, compound descriptions that transform into each other on the way to a final manifestation of the original tree, whatever kind of tree that may be (page xciv).

However, for the moment, on with the beech! For me, the reference to gold in line 4 could evoke a chest of treasure, or the warming gold of flames of a beech-log fire. It could be the gilded decorations on a book, perhaps a book valued like gold. I even see the glinting gold of the beech leaves in the last chilly days of autumn:

Photo of golden beech leaves (by Jonathan Billinger) from Wikimedia Commons (licence CC BY-SA 2.0).

But let us place such imaginings against the reference Tupper picks out in line 8 of Riddle 20, with its very similar gold ofer geardas referring to the making of a sword. Perhaps, in our current riddle, the tree is at this point being turned into the exultant battle-weapon that, after the hiatus of the middle of this line, both closes the end of this line and opens the next. In that next line, we have moved on to a heightened moment, as we are presented with the heroic warrior’s joyful battle-weapon. This, whether it be battering ram or shield, could be the final transformation of the tree and therefore the solution to the riddle, particularly since byreð (bears) and oþrum (to another) – the words still visible in the largely obliterated last lines – could be references to carrying, defending or attacking in battle.

But is it a beech battering ram, a beechwood shield, or another kind of wood? Let’s consider oak. As noted earlier, like the beech, the oak too can be glorious:

Photo of oak tree near the Teign (by Derek Harper) from Wikimedia Commons (licence CC BY-SA 2.0).

So of course can the hazel tree, and both oak and hazel produce catkins and nuts - sources of protein for squirrels and birds – “flourishing life-givers” indeed. And here I am going to give the hazel tree a little look-in as I think this photograph really suggests that life-giving element well:

Photo of Common Hazel fruits (by H. Zell) from Wikimedia Commons (licence CC BY-SA 3.0).

However, oak is more prized for its strength and density, and therefore stands up better in terms of the references to nourishment, stability and power in lines 2 and 3. As for the wifes sond (woman’s love missive), here oak for me also trumps beech: oak galls were used as the main ingredient in writing ink at this time and oak bark was also used by tanners to tan the leather that formed the vellum of manuscripts. I more easily imagine “gold at the hearth” as an allusion to a strong oaken chest of treasure than a chest made of beech. It could of course also allude to the decoration of a manuscript; oak, like beech, makes great gold flaming firewood; and oak, perhaps more than beech, could at this point be in the process of being fashioned into a weapon. Battering rams were typically made of oak, ash or fir, although I am not sure if they would have included gold, as perhaps a shield might. However, while a shield is used in defence, what more celebratory, joyful or “exultant” weapon can there be than the thrusting battering ram?

Well, in the end, there’s no clear answer – because of course we have, to this riddle, no end. Whether it refers to beech, oak, hazel or book, what seems clear is that this riddle is tracking, and celebrating, a tree’s metamorphosis through a series of kenning-like phrases – and that perhaps (given the last lines, which presumably hold the essential clue, are practically obliterated), it is only appropriate that we do not know for sure what the tree’s final transformation is. Indeed, if this is a good riddle, such an uncertainty in our knowledge and our guessing would seem fitting. Otherwise those last invisible words become redundant...and no poet worth the name wants redundancy.

References and Suggested Reading:

Crossley-Holland, Kevin, trans. The Exeter Book Riddles. London: Enitharmon, 2008.

Porter, John. Anglo-Saxon Riddles. Hockwold-cum-Wilton: Anglo-Saxon Books, 1995 and 2013.

Tupper, Frederick, Jr. Riddles of the Exeter Book. Boston, Ginn, 1910.

Williamson, Craig, trans. The Complete Old English Poems. Penn State University Press, 2017.

Williamson, Craig. The Old English Riddles of the Exeter Book. Chapel Hill: University of North Caroline Press, 1977.

Tags: anglo saxon exeter book riddles old english solutions judy kendall riddle 92

Related Posts:

Commentary for Exeter Riddle 20

Exeter Riddle 20