Exeter Riddle 1 in Spanish / en Español

MEGANCAVELL

Date: Tue 22 Jun 2021Dr. José Antonio Alonso Navarro holds a PhD in English Philology from the Coruña University (Spain) and a BA in English Philology from the Complutense University of Madrid (Spain). Currently, Alonso Navarro is a Full Professor of History of the English Language at the National University of Asuncion (Paraguay). His main interest revolves around the translation of Middle English texts into Spanish. Needless to say, he is also very enthusiastic about Old English riddles.

El Dr. José Antonio Alonso Navarro es Doctor en Filología Inglesa por la Universidad de La Coruña (España) y Licenciado en Filología Inglesa por la Universidad Complutense de Madrid (España). Actualmente, Alonso Navarro es Catedrático de Historia de la Lengua Inglesa en la Universidad Nacional de Asunción (Paraguay). Su principal interés gira en torno a la traducción de textos del inglés medio al español. No hace falta decir que también está muy entusiasmado con los acertijos en inglés antiguo.

Hwylc is hæleþa þæs horsc ond þæs hygecræftig

þæt þæt mæge asecgan, hwa mec on sið wræce,

þonne ic astige strong, stundum reþe,

þrymful þunie, þragum wræce

5 fere geond foldan, folcsalo bærne,

ræced reafige? Recas stigað,

haswe ofer hrofum. Hlin bið on eorþan,

wælcwealm wera, þonne ic wudu hrere,

bearwas bledhwate, beamas fylle,

10 holme gehrefed, heahum meahtum

wrecen on waþe, wide sended;

hæbbe me on hrycge þæt ær hadas wreah

foldbuendra, flæsc ond gæstas,

somod on sunde. Saga hwa mec þecce,

15 oþþe hu ic hatte, þe þa hlæst bere.

¿Quién hay de entre los hombres sabios y prudentes que puedan contar quién me impulsa a viajar, cuándo yo me elevo poderosamente, a veces de manera salvaje y retumbando con fuerza, y cuándo en ocasiones yo mismo me impulso a viajar a través de la tierra, quemando casas y saqueando palacios? El humo gris asciende hasta los tejados. Hay un estruendo sobre la tierra, la muerte violenta de hombres cuando agito bosques y arboledas que crecen con rapidez, cuando derribo árboles, protegido por el océano, obligado a viajar por los poderes en las alturas, (y) forzado a moverme a lo largo y ancho; sostengo en la espalda aquello que antes había cubierto el rango de los habitantes de la tierra, carne y hueso, nadando juntos. Decid qué es lo que me cubre o cómo se me llama, (y) quién sostiene la carga.Tags: anglo saxon exeter book old english riddle 1 José Antonio Alonso Navarro

Related Posts:

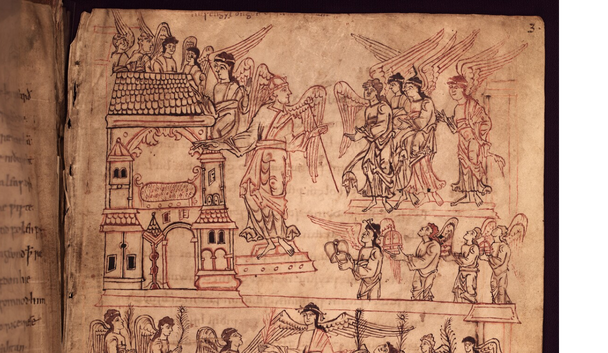

Exeter Riddle 1

Commentary for Lorsch Riddle 1

NEVILLEMOGFORD

Date: Mon 07 Jun 2021Matching Riddle: Lorsch Riddle 1

This is my first commentary on the Lorsch Riddles. And it is fair to say that it is about time!

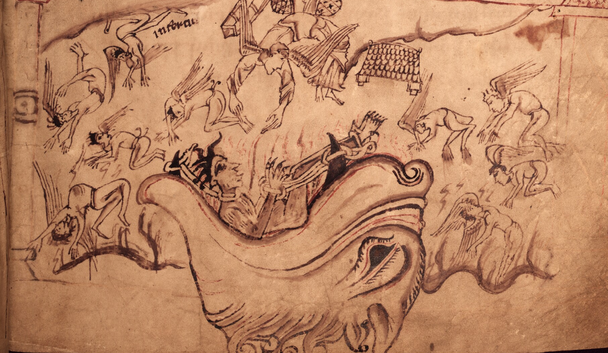

No—what I mean is that the riddle is about time! The speaker and the likely solution are “humankind.” But the real focus is Christian world-time. It begins with Adam and Eve on the sixth day of Creation (line 2), and then turns to human life on earth (lines 3-6) and in the grave (lines 7-9), before moving to the Final Judgement (lines 10-11) and ending with the soul in eternal bliss or damnation (line 12). If I had to sum this riddle up in a song lyric, it would be The Bangles’ “Time, time, time.”

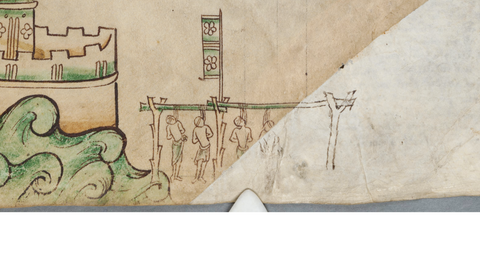

Meditations on the nature of humankind’s place in Christian time are extremely common in the early medieval period. You can find them in all kinds of forms and genres, from letters and poems to prayers and homilies, and from theological and hagiographical texts to charters and legal texts. Such meditations typically contrast the mutable and unpredictable times of now with the fixity and stability of the future world to come in heaven.

A good example of a meditation on time appears in one of my favourite medieval Latin poems, The Destruction of Lindisfarne, written by the eighth century Northumbrian churchman and scholar, Alcuin of York.

Quid iam plura canam? Marcescit tota iuventus,

Iam perit atque cadit corporis omne decus…

Hic variat tempus, nil non mutabile cernis:

Illic una dies semper erit, quod erit.

[What more shall I now write? All youth withers,

all material beauty fades and falls…

Over here, time changes and everything you see is changeable.

Over there, one day is always what it will be.]

–Alcuin. The Destruction of Lindisfarne, lines 111-2, 121-2.

These kinds of sentiments usually have a moralistic and didactic purpose. You may already know about memento mori, the motif in medieval and modern art where the reader, viewer, or listener is reminded of their own death, with the intention that they should correct their sins before it is too late. For example, the following extract from the Old English poem, The Seafarer, reminds the reader that they should put their wealth to good use when still living, because gold will not save one’s soul at the Last Judgement.

Ne mæg þære sawle þe biþ synna ful

gold to geoce for godes egsan,

þonne he hit ær hydeð þenden he her leofað.

[If they have already hidden it whilst they live here, gold cannot help the soul full of sin in the face of the terrible might of God.]

–The Seafarer, lines 100-102.

I get a very similar vibe from today’s riddle. It is a moralistic work, with lots of terror and dread, warning the reader that their time on earth is short. Of course, some might dispute that it is a riddle at all! However, as I hope to show you, it still has some playful and riddle-like aspects to it.

The riddle—if we can all agree to call it that—begins with the explanation that the speaker’s “fates” (fata) are changeable. This doesn’t mean that each individual will have a different fate, but rather that humankind as a whole passes through different “fates”—from the start to the end of the world and beyond. #LatinGrammar fans will notice that this is described using the dative of possession (mihi), which is also used widely in the Bern Riddles.

Riddles often talk about family relations—they give us an ostensibly extraordinary example of parentage and then challenge us to explain it. In this tradition, line 2 tells us about a “pater supremus” (supreme father), who created his child without a mother. As you may have already realised, this father is God, who created Adam from the earth’s soil on the sixth day of Creation.

The next two lines jump forward to the world after the Fall of Adam and Eve, when human mothers and fathers are creating more and more children! The riddle describes this as if it were a single instance of childbirth. Of course, the riddle is really about a whole host of births throughout the generations, viewed across the whole panorama of human time. This is a very nice example of synecdoche (pronounce it “se neck dockie”)—the use of a part to describe a whole. Intriguingly, Patrizia Lendinara has suggested (page 80) that the reference to semen (“seed”) in line 3 is a bilingual pun on the Old English word sæd (“seed”) and the name of one of Adam’s sons, Seth. However, I’m not sure that I am entirely convinced!

Line 4 includes a word that crops up in several other medieval riddle collections—venter (“belly, womb, bowels”). In other riddles, this word can refer figuratively to all kinds of things, such as the heat of a spark (Aldhelm Riddle 93) or the holes of a sponge (Bern Riddle 32). However, the Lorsch riddle uses this in an entirely conventional way to describe a human womb. You could even say that this conventional use is itself unconventional in riddling terms. Karl Mist, who rendered this riddle into German in the Corpus Christianorum Series Latina edition of the riddles, translated this section in terms of an extended metaphor about a plant, but in fact there is very little metaphorical language used here—it is all quite literal.

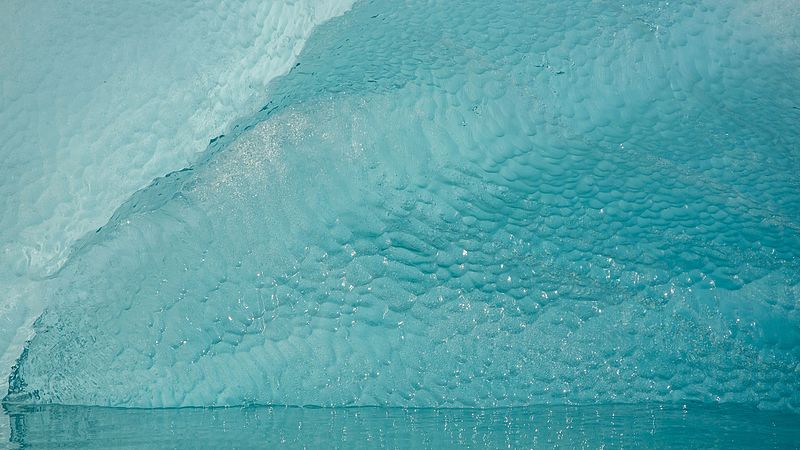

Lines 5 and 6 describe the perils of the human age: today’s living humans are superstites (“ancestors, survivors”), who live in a turbulent world of fear and dread. The riddle describes how they “bristle at” or “stiffen in” (rigescere) “ice-cold death” (gelida sub morte). This phrase may refer to the corpse in rigor mortis, or alternatively to the paralysing fear in the horrifying face of death. Whatever it means, it is very memento mori!

Lines 8, 9 and 10 describe the body lying in the grave, hidden and waiting to be resurrected at the end of the world. Line 8 invites us to guess the identity of the mother who embraces the corpse. I am pretty sure that she is the earth, from whose soil the first man and woman are created in Genesis 2:7—the Latin terra (“earth”) is a feminine noun.

The final lines look towards the last Judgement, the time in the future when Christians believe God will resurrect and then judge the dead. Here, the riddle comes full circle as the father “recreates” (recreare) his children, before sending them off to everlasting bliss or annihilation. This cyclical motif is somewhat different to the usual, linear way of thinking about Christian world, i.e., as a long line from one point (“the creation of the world”) to another (“the end of the world”).

So, there we have it—a miniature panorama of Christian world-time in 12 lines! It isn’t the most cryptic of riddles, but it rather nicely grafts the cyclic motif of birth onto linear Christian time.

References and Suggested Reading:

“Aenigma Laureshamensia [Lorsch Riddle] 1” in Tatuini Opera Omnia. Edited by Fr. Glorie. Translated by Karl Minst. Corpus Christianorum Series Latina 133. Turnholt: Brepols, 1958. Page 347.

“The Seafarer.” In George Philip Krapp, & Elliott Van Kirk Dobbie (eds.), The Exeter Book, The Anglo-Saxon Poetic Records: A Collective Edition. Volume 3. New York: Columbia UP, 1936.

Alcuin of York. “The Destruction of Lindisfarne.” In Peter Godman (ed. & trans.), Poetry of the Carolingian Renaissance. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1985. Pages 126–39 (133).

Lendinara, Patrizia. “Gli “Aenigmata Laureshamensia.”” Pan, Studie dell’Istuto di Filogia Latina, Volume 7 (1981). Pages 73-90.

Tags: latin