Exeter Riddle 42

MEGANCAVELL

Date: Thu 30 Jul 2015Matching Commentaries: Commentary for Exeter Riddle 42

This riddle translation comes to us from Jennifer Neville, Reader in Early Medieval Literature at Royal Holloway University of London. She has published on several of the riddles and is currently working on a book about them. You may remember her from her brilliant translation and commentary of Riddle 9.

Ic seah wyhte wrætlice twa

undearnunga ute plegan

hæmedlaces; hwitloc anfeng

wlanc under wædum, gif þæs weorces speow,

5 fæmne fyllo. Ic on flette mæg

þurh runstafas rincum secgan,

þam þe bec witan, bega ætsomne

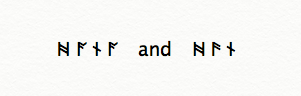

naman þara wihta. Þær sceal Nyd wesan

twega oþer ond se torhta æsc

10 an an linan, Acas twegen,

Hægelas swa some. Hwylc þæs hordgates

cægan cræfte þa clamme onleac

þe þa rædellan wið rynemenn

hygefæste heold heortan bewrigene

15 orþoncbendum? Nu is undyrne

werum æt wine hu þa wihte mid us,

heanmode twa, hatne sindon.

I saw two amazing creatures —

they were playing openly outside

in the sport of sex. The woman,

proud and bright-haired, received her fill under her garments,

5 if the work was successful. Through rune-letters

I can say the names of both creatures together

to those men in the hall

who know books. There must be two needs

and the bright ash —

10 one on the line — two oaks

and as many hails. Who can unlock

the bar of the hoard-gate with the power of the key?

The heart of the riddle was hidden

by cunning bonds, proof against the ingenuity

15 of men who know secrets. But now

for men at wine it is obvious how those two

low-minded creatures are named among us.

Notes:

This riddle appears on folio 112r of The Exeter Book.

The above Old English text is based on this edition: Elliott van Kirk Dobbie and George Philip Krapp, eds, The Exeter Book, Anglo-Saxon Poetic Records 3 (New York: Columbia University Press, 1936), pages 203-4.

Note that this edition numbers the text Riddle 40: Craig Williamson, ed., The Old English Riddles of the Exeter Book (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1977), page 95.

This post, specifically the lineation of the translation, was edited for clarity on 30 November 2020.

Tags: anglo saxon exeter book riddles old english solutions riddle 42 jennifer neville

Related Posts:

Commentary for Exeter Riddle 42

Commentary for Exeter Riddle 77

Exeter Riddle 9

Commentary for Exeter Riddle 41

MEGANCAVELL

Date: Tue 21 Jul 2015Matching Riddle: Exeter Riddle 41

Riddle 41’s commentary, like its translation, comes to us from the fab Helen Price:

Poor Riddle 41, it’s unlikely to ever be named anyone’s favourite Exeter Book riddle. In fact, it has struggled to receive any real attention whatsoever *cue sad violin music*. Most riddle commentators have either glossed over it or attempted to brush it under the carpet in the hope that it’ll go away…it hasn’t. The longest discussion I have been able to find on Riddle 41 is actually arguing that it is a continuation of the previous riddle (see Konick). *Sigh*. However, this absence of discussion is not entirely unjustified, and is mainly due to the fact that the beginning of the riddle appears to be missing, leaving only the final eight and a half lines intact. Apparently, it has proved difficult and unappealing to discuss something when a chunk of it seems to be absent. Well fear not noble readers, because I am about to do just that! Well, not quite, but here’s hoping I can say something to give this plucky half of a riddle a moment in the spotlight.

Somewhat surprisingly for a text from the Exeter Book, the missing first lines of Riddle 41 are not due to damage of the actual folio page of the manuscript, as is the case with folios 117-130 of the Exeter Book – these folios are scarred by a large burn which increases in size the further through the manuscript you go. However, the fact that Riddle 40 seems to end as abruptly as Riddle 41 starts suggests that something has definitely gone awry.

Some scholars have suggested that the incomplete state of both riddles is due to a scribal error. The Exeter Book manuscript appears to have been copied by just one scribal hand. I suppose when you are hand-copying that much text, probably by candle light, a little missed page here and there is forgivable. However, it is impossible to know (unless the missing Exeter Book page somewhat miraculously turns up from behind a dusty shelf somewhere) whether this is a mistake on the part of the scribe or whether a folio just never made it into (or has been removed from) the bound manuscript. But this uncertainty can also give us food for thought. Thoughts such as: how do we read texts which are (excuse the expression) not all there? What can we glean from the bit of Riddle 41 which we do have? And how can literary context help us to make sense of these few disjointed lines?

And so to the text itself… I can’t help but smile every time I start reading Riddle 41. Edniwu (“renewed!”) it chimes, completely out of the blue. I had to resist placing a little exclamation mark after this opening word in my translation (it turns out I couldn’t resist adding it in here). Scribal error or missing folio, it is a wonderful coincidence that the start of this surviving bit of the riddle happens to have landed at this point. “Renewed” from what? By what? As what? Riddles are fond of their internal mysteries and games (as you will no doubt be more than familiar with from the other riddles and fantastic commentaries posted so far on this website), but here it is the manuscript itself which has landed us with these questions to ponder…and ponder I shall.

Aside from those who have argued that Riddle 41 is a continuation of Riddle 40 (see Konick), the solution “water” has almost unanimously been agreed by editors and commentators alike. I am firmly in favour of this solution for a number of reasons, most of which are drawn from evidence outside of the riddle itself.

“Water Droplet” photo (by fir0002 | flagstaffotos.com.au), licensed under GFDL 1.2 via Wikimedia Commons.

The surviving lines offer a reasonable indication of Riddle 41’s solution; a substance which is vital to human beings and which plays a key part in the production of life. But, let’s face it, on the surface of this text there is little to conclusively make water, as opposed to say “air” or “food” or some other important life-sustaining substance, the most viable solution. However, when we read and understand Riddle 41 in the context of both other water riddles and water in early medieval poetic texts more generally, then things start to become a little clearer and more convincing.

One of the stock ways to conceptualise water which circulates in early English poetic contexts is the idea of water as a mother figure. This idea appears in the form of two different motifs across the riddles. Firstly, there is the notion that water is a substance which begets itself in different forms i.e. water becomes ice and ice melts back into water (this was discussed far more competently by Britt Mize in his marvellous commentary post for Riddle 33). Obviously, we can’t see this directly at work in Riddle 41 but, bearing in mind the way that the riddles tend to draw on similar themes and stock descriptions, I would like to muse that perhaps this is the point where we enter the surviving part of Riddle 41. Remember that opening declaration “renewed” which forms the first half line? Well, it might not be too farfetched to suggest that the first part of the riddle has described water in one state (perhaps in the form of ice as in Riddle 33), and when ice melts it is “renewed” in a new form of itself, i.e. liquid water.

This seal agrees with the metaphor. Photo by Megan Cavell.

As you may well already be familiar with from previous posts, the Exeter Book riddles were copied and circulated in an intellectual context of book-learning. As such, the Exeter Book riddles often riff on a theme or way of describing something. Quite often these ideas are drawn from Anglo-Latin riddles from the likes of Aldhelm (7th century) and sometimes the even earlier (5th century) enigmata of Symphosius.

A key example of water as “life-giver to all things” motif can be seen at work in Aldhelm’s fountain enigma.

Per cava telluris clam serpo celerrimus antra

Flexos venarum girans anfractibus orbes;

Cum caream vita sensu quoque funditus expers,

Quis numerus capiat vel quis laterculus aequet,

Vita viventum generem quot milia partu?

His neque per cselum rutilantis sidera sperae

Fluctivagi ponti nec compensantur harenae.

(I creep stealthily and speedily through empty hollows of the earth, winding my twisted route along the curves of its arteries. Although I am devoid of life and utterly lacking in sensation, what number could embrace or what calculation encompass the many thousands of living creatures which I engender through birth? Neither the stars of the glowing firmament in the sky nor the sands of the billowing sea can equal them.) (Lapidge and Rosier, pages 85-6)

Though the title of the enigma is “fountain”, it is the properties of the water which are most prominent in the poem. As you can see, the poem focuses on the life-giving properties of water, specifically characterizing it as engendering all living creatures.

Water is also presented as engendering multitudes of living things elsewhere in the Exeter Book riddles and more widely in Old English poetry. [SPOILER ALERT: reference to a later Exeter Book riddle about to come up!] Riddle 85 which is also usually solved as “water”, shows this idea at work with the lines:

nænig oþrum mæg

wlite wisan wordum gecyþan

hu mislic biþ mægen þara cynna (lines 6-8)

(none to any other can, with wise words, expound its features, how copious is the multitude of its kin.)

Riddle 85 also directly refers to its subject as moddor (mother) a few lines later. I don’t want to spoil the fun of Riddle 85 by giving too much away, so enough said about that for now. But you get the picture – the life-giving/sustaining properties of water are presented by characterising it as mother to all life.

So we can begin to see that when Riddle 41 refers to its subject as þæt is moddor monigra cynna (line 2) (which is the mother of many kins), that there is a literary context which supports the answer specifically as water rather than another life-sustaining object/substance such as food or air. But there are also other clues which support the solution “water” which we can pick up from looking elsewhere in the surviving body of early English poetry.

As you will have surely picked up from this website, the Exeter Book riddles love puns. Water is a substance whose qualities make it ripe for punning – a poet brims with verbs and participles to flood their lines with gushing descriptions, overflowing with watery associations! Raymond Tripp (pages 65-6) talks through one such particular passage in Beowulf (lines 2854-61) where Wiglaf attempts to save Beowulf after the fight with the dragon. Tripp explains that these lines of Beowulf demonstrate how the Christian poet’s worldview is reflected in the poems use of humour by using an “extended concatenation of ‘water’ images […] to show the utter uselessness of pagan ‘baptism’ to save dying men” (Tripp, page 65).

The latter part of Riddle 41 may be read as no exception to this tradition of punning. Lines six and seven of Riddle 41 state:

Ne magon we her in eorþan owiht lifgan,

nymðe we brucen þæs þa bearn doð.

(We cannot, by any means, live here on earth unless we profit as those children do.)

The word brucen can mean either “to profit” or “consume” food or drink – marking the subject as something which is taken into the body. Bearing in mind the use of water puns in poems such as Beowulf, it is also possible that the word brucen is itself nodding to the noun broc (brook). While these two words do not share the same root, the word (ge)brocen is a past participle form of (ge)brucan which has the attested spelling variation of (ge)brocen, suggesting that a lexical connection between brucen (to profit/consume) and the noun broc (a brook) may have made sense to an early medieval reader/listener as a water-based pun.

So, it might be that Riddle 41 is a little bit broken but it definitely still has its charms. Its brokenness forces us to think about Riddle 41’s place in a wider literary context, and highlights the shared motifs which circulate not only in early medieval riddle poems but more broadly across surviving early English poetry. Now, in Riddle 41’s very own words, þæt is to geþencanne þeoda gehwylcum (that is something for people to think about).

Bibliography and Suggested Reading

Dictionary of Old English: A-G Online. Ed. by Antonette diPaolo Healey, Dorothy Haines, Joan Holland, David McDougall, and Ian McDougall, with Pauline Thompson and Nancy Speirs. Web interface by Peter Mielke and Xin Xiang. Toronto: Dictionary of Old English Project, 2007. [with the next roll-out, you’ll be able to access the DOE a set amount of times for free!]

Konick, Marcus. “Exeter Book Riddle 41 as a Continuation of Riddle 40.” Modern Language Notes, vol. 54 (1939), pages 259-62.

Lapidge, Michael and James Rosier. Aldhelm: The Poetic Works. Woodbridge: Brewer, 1985.

Muir, Bernard J., ed. The Exeter Anthology of Old English Poetry. Vol II Commentary. Exeter: Short Run, 2000.

Tripp, Raymond P. “Humour, Word Play, and Semantic Resonance in Beowulf.” In Humour in Anglo-Saxon Literature. Ed. by Jonathan Wilcox. Cambridge: D. S. Brewer, 2000, pages 49-70.

Tags: anglo saxon exeter book riddles old english solutions riddle 41 helen price

Related Posts:

Commentary for Exeter Riddle 33