Date: Mon 24 Feb 2014

Matching Commentaries:

Commentary for Exeter Riddle 19

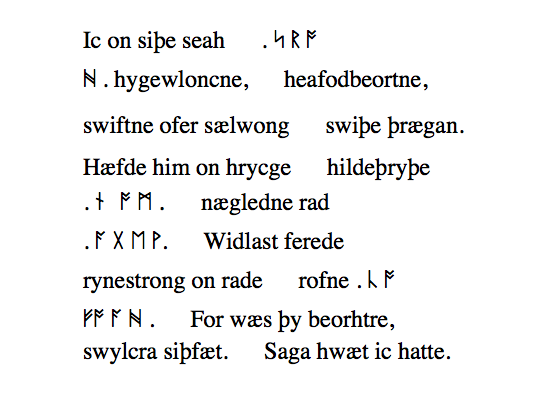

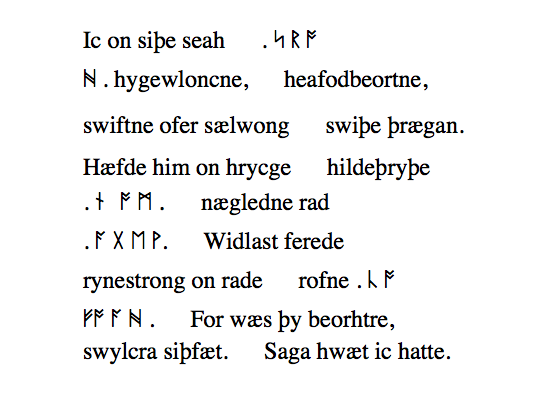

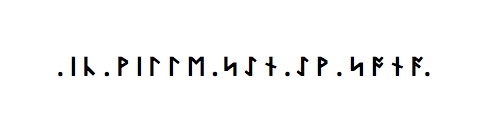

We have a slight complication this week, folks: RUNES! Runes are great, but they can be a bit of a technological nightmare, so bear with me. If you can’t see the runes in the Old English riddle below, scroll down to the bottom of this post where you'll find a screenshot. Not ideal, I know, but this way everyone should get to revel in the glory of runes. Aaaaaaaaand, go!

Original text:Ic on siþe seah . ᛋ ᚱ ᚩ

ᚻ . hygewloncne, heafodbeortne,

swiftne ofer sælwong swiþe þrægan.

Hæfde him on hrycge hildeþryþe

5 . ᚾ ᚩ ᛗ . nægledne rad

. ᚪ ᚷ ᛖ ᚹ. Widlast ferede

rynestrong on rade rofne . ᚳ ᚩ

ᚠᚩ ᚪ ᚻ . For wæs þy beorhtre,

swylcra siþfæt. Saga hwæt ic hatte.

Translation:I saw on a journey a mind-proud,

bright-headed S R O H,

the swift one running quickly over the prosperous plain.

It had on its back a battle-power,

5 the N O M rode the nailed one

A G E W. The far-stretching track conveyed,

strong in movement on the road, a valiant C O

F O A H. The journey was all the brighter,

the expedition of such ones. Say what I am called.

Click to show riddle solution?

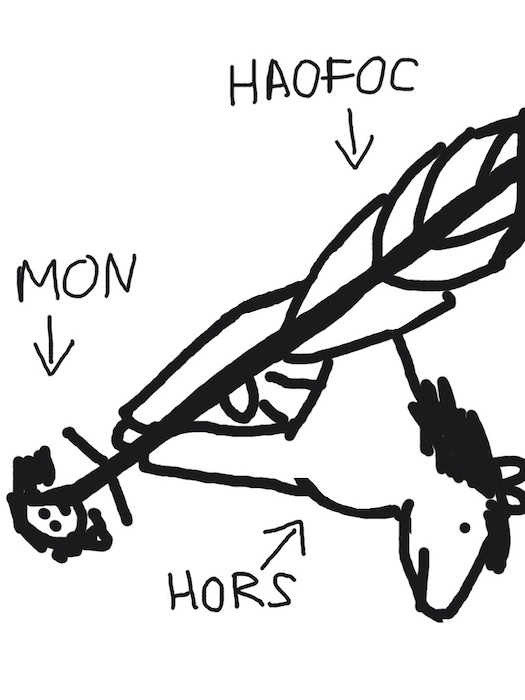

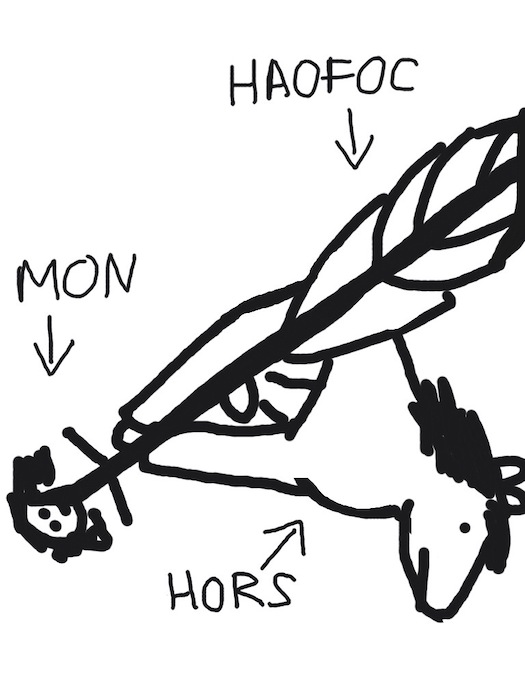

Ship, Falconry/Horseman and hawk [sometimes with wagon/servant] and Writing

Notes: This riddle appears on folio 105r of The Exeter Book.

The above Old English text is based on this edition: Elliott van Kirk Dobbie and George Philip Krapp, eds, The Exeter Book, Anglo-Saxon Poetic Records 3 (New York: Columbia University Press, 1936), pages 189-90.

Note that this edition numbers the text Riddle 17: Craig Williamson, ed., The Old English Riddles of the Exeter Book (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1977), page 78.

Screen shot for the runes:

Tags:

anglo saxon

exeter book

riddles

old english

solutions

riddle 19

Related Posts:

Commentary for Exeter Riddle 19

Exeter Riddle 24

Exeter Riddle 58

Commentary for Exeter Riddle 17

MEGANCAVELL

Date: Tue 24 Dec 2013Matching Riddle: Exeter Riddle 17

This post once again comes from Wendy Hennequin:

Translation is a tricky business at its best. Lines 4b-5a, for instance, has a grammatical structure that we rarely use in Modern English, and its first word, sped, has multiple and varied meanings. Which one of these meanings should I choose? How should I render that grammatical structure? Riddles add another layer to the problems, as riddles often play on multiple meanings, sounds, and puns. The word fylle, “fullness,” in line 5a, may be a pun on fiell, also spelled fyll, “destruction, death, fall.” How do I translate a pun which doesn’t exist anymore?

To make matters more difficult for myself, I like to render my Modern English translations into the correct Old English poetic form, as much as is possible without losing meaning. Meaning must be the ultimate priority, since a translation is useless if it doesn’t tell the reader, as far as is possible, what a text says.

But it is also good to preserve the poetry, to give the reader an idea of the sound and feel of the original text. I therefore try to put the text into the correct Old English meter and adhere to the rules of Old English alliteration. I use Sievers’ types for the meter (Sievers’ types, named for the scholar who codified them, are the five patterns of stress in Old English half-lines. You can read about them here), though I don’t try to match the meter of the original half-line with the meter of the translation. It is often impossible to match the original metrical type and preserve the meaning, though sometimes it does happen.

Sometimes, it is not possible to translate meaning and render proper meter and alliteration. In those cases, I preserve meaning but relax the poetry. Generally, it is possible to keep the meter if I let the alliteration go. But in some cases, I am able to rescue both meter and alliteration by using the Old English poetic technique of variation. Line 1b in Riddle 17, when translated literally into Modern English, doesn’t have enough syllables to make a half-line: “I am protector of my flock.” In cases like these, I often use an alternate meaning for a word already in the line: mundbora, “protector,” is literally “hand-ruler.” By putting both meanings in the line—in other words, repeating mundbora as a variation of itself—I can render the poetry without adding or losing meaning, though it does regrettably add emphasis.

Even in the best of times, my Modern English translations are not as poetic as the originals. Modern English grammar sometimes makes for clumsy Old English poetry, as it does in lines 4a and 9a of my translation. And Modern English syntax often necessitates moving words from one line to another, and even moving entire half-lines, in order to make grammatical sense.

Perhaps my translations are not the best or most accurate, nor even the most poetic. But I hope to preserve the meaning of the poem and give at least a good idea of what Old English poetry sounds like.

References and Suggested Reading:

Clark Hall, J. R. A Concise Anglo-Saxon Dictionary. 4th ed. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1960.

Osborn, Marijane. “‘Skep’ (Beinenkorb, *beoleap) as a Culture-Specific Solution to Exeter Book Riddle 17.” ANQ, vol. 18 (2005), pages 7-18.

Sorrell, Paul. “A Bee in My Bonnet: Solving Riddle 17 of the Exeter Book.” In New Windows on a Woman’s World: Essays for Jocelyn Harris. Edited by Colin Gibson and Lisa Marr. Dunedin, NZ: University of Otago Press, 2005, pages 544-53.

Wilcox, Jonathan. “New Solutions to Old English Riddles: Riddles 17 and 53.” Philological Quarterly, vol. 69 (1990): pages 393-408.

Note that this post and the related translation were edited and restructured for clarity on 15 January 2021.

Tags: anglo saxon exeter book riddles old english riddle 17 translation style wendy hennequin

Related Posts:

Exeter Riddle 17