Date: Mon 21 Apr 2014

Matching Commentaries:

Commentary for Exeter Riddle 22

Original text:Ætsomne cwom LX monna

to wægstæþe wicgum ridan;

hæfdon XI eoredmæcgas

fridhengestas, IIII sceamas.

5 Ne meahton magorincas ofer mere feolan,

swa hi fundedon, ac wæs flod to deop,

atol yþa geþræc, ofras hea,

streamas stronge. Ongunnon stigan þa

on wægn weras ond hyra wicg somod

10 hlodan under hrunge; þa þa hors oðbær

eh ond eorlas, æscum dealle,

ofer wætres byht wægn to lande,

swa hine oxa ne teah ne esna mægen

ne fæthengest, ne on flode swom,

15 ne be grunde wod gestum under,

ne lagu drefde, ne on lyfte fleag,

ne under bæc cyrde; brohte hwæþre

beornas ofer burnan ond hyra bloncan mid

from stæðe heaum, þæt hy stopan up

20 on oþerne, ellenrofe,

weras of wæge, ond hyra wicg gesund.

Translation:Together 60 men came

riding to the bank on horses;

11 horsemen had

noble steeds, 4 had white ones.

5 The warriors could not pass over the water,

as they intended, but the sea was too deep,

the terrible tumult of the waves, the banks too high,

the streams too strong. Then the men began

to climb up on the wagon together with their horses,

10 to load under the pole; then the wagon carried the horses,

mounts and men, proud in spears,

to land across the bay of the water,

in such a way that no ox pulled it, nor the strength of slaves,

nor a draught horse, nor did it swim on the water,

15 nor did it wade along the ground under its guests,

nor did it disturb the waters, nor fly in the air,

nor turned back; nevertheless it brought

the warriors over the stream, and their horses with them

from the high bank, so that they stepped up

20 onto the other, strong in courage,

the men from the waves, and also their horses, unharmed.

Click to show riddle solution?

Ursa Major, (days of the) month, bridge, New Year, stars

Notes: This riddle appears on folios 106r-106v of The Exeter Book.

The above Old English text is based on this edition: Elliott van Kirk Dobbie and George Philip Krapp, eds, The Exeter Book, Anglo-Saxon Poetic Records 3 (New York: Columbia University Press, 1936), pages 191-2.

Note that this edition numbers the text Riddle 20: Craig Williamson, ed., The Old English Riddles of the Exeter Book (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1977), pages 80-1.

Tags:

anglo saxon

exeter book

riddles

old english

solutions

riddle 22

Related Posts:

Exeter Riddle 3

Exeter Riddle 26

Exeter Riddle 49

Commentary for Exeter Riddle 21

MEGANCAVELL

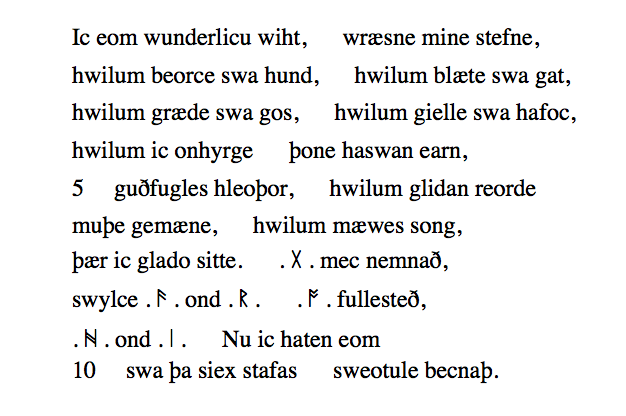

Date: Sun 06 Apr 2014Matching Riddle: Exeter Riddle 21

Boy, we sure are plowing through these riddles, aren’t we? Get it? Get it? If not, you must have forgotten the solution to Riddle 21: plough or plow (depending on how you prefer to spell)! If you prefer to spell like someone from early medieval England, then you’d be spelling it sulh. There isn’t a great deal of debate over this riddle’s solution, which – I have to say – is kind of obvious. So instead of scholarly debate, I’m going to impress you with pictures. And also details and such-like.

Here is a reproduction of a plough drawing in an eleventh-century calendar now housed in the British Library (Cotton MS Tiberius B V/1, folio 3r):

From The New Gresham Encyclopedia, available free online at Project Gutenberg. The original, in all its colourful glory, is digitized here.

The (quite lumpy-looking, though nonetheless smiley) team of oxen is nicely visible here, as are the various parts of the plough. These include the share (the bit that breaks up the earth) and the coulter (the bit that makes a groove for sowing seeds), which may be represented in the poem as the creature’s neb (nose), as well as the weapon that pierces the plough’s head (similar to the orþoncpil (skillful spear) driven through its back). Here’s a picture of an early medieval iron coulter from North Lincolnshire Museum:

Image from the Portable Antiquities Scheme (licence: CC BY-SA).

In addition to the specifics of actual ploughing (i.e. the description of the object laying horizontally and being pushed along, the sowing of seeds, the churning up of earth to make a path and the elements that pierce the object’s body), this poem provides useful information on an important aspect of the early medieval world: slavery. Whether born into it, taken in warfare or punished for criminal activity, slaves were common in this period. Despite the widespread nature of slavery at this time, few slaves are given voice in Old English literature, which is one of the reasons Riddle 21 is such an important text.

“Why the plough?” you might ask. “Surely there are all sorts of objects and animals that could have been chosen to represent an enslaved person in early medieval England.” That’s true, of course, and there are other riddles that give evidence of slavery. However, the fact that ploughing was a common role for slaves (according to the Domesday Book) goes some way to explaining the riddler’s choice. The unhappy conditions of slavery are also expounded in the Colloquy that Ælfric of Eynsham wrote in order to help his students learn Latin. It introduces a variety of figures who are quizzed about their roles and responsibilities. In a particularly empathetic passage, the enslaved ploughman cries: O! O! magnus labor. etiam, magnus labor est, quia non sum liber in Latin, or Hig! Hig! micel gedeorf ys hyt. / Geleof, micel gedeorf hit ys, forþam ic neom freoh (34-5) (Oh! Oh! The labour is great. Yes, the labour is great, because I am not free) in Old English (at page 21, lines 34-5). This is a rare example of a slave having a voice at all, let alone one that demands empathy.

Dexter cattle at Bede’s World in Jarrow. Photo courtesy of C.J.W. Brown.

Riddle 21 is another example of a metaphorical slave describing her/his condition. In fact, this riddle provides us with information about the type of slave the poem depicts: this slave has been brought from the forest, bound and borne into the settlement (brungen of bearwe, bunden cræfte, / wegen on wægne). The implication of the half-line har holtes feond (the old foe of the forest) is that the ploughman or ox responsible for clearing the land takes slaves during battle, an idea driven home by the weapon-imagery toward the end of the poem.

This context of slavery makes the poem’s innuendo pretty disturbing, if you ask me (Murphy talks about this innuendo at pages 175-6 of his book, cited below). All the riddle’s references to the prone speaker being aggressively pushed by its master (class/status implications are also clear when the poem refers to the plough’s hlaford (lord) twice) who sows seed are brought to a head by the final lines’ description of being served from behind. It doesn’t take an especially pervy imagination to see how this could be read sexually, particularly given the connotations of “plowing” in Modern English. Of course, the reference to the speaker’s steort (tail) and tearing teeth (ic toþum tere) may introduce a bestial element that only makes things worse.

All in all, Riddle 21 presents us with a creature forced to perform hard labour for its captor. I’d like to think that this image is a sympathetic one, but the introduction of innuendo may imply that the enslaved victim is the butt of the joke. Or maybe the fact that we’re dealing with an object rather than a person can ease our discomfort. I haven’t decided yet.

References and Suggested Reading:

Ælfric of Eynsham. Ælfric’s Colloquy. Edited by G. N. Garmonsway. London: Methuen, 1939.

Bintley, Michael D. J. “Brungen of Bearwe: Ploughing Common Furrows in Riddle 21, The Dream of the Rood, and the Æcerbot Charm.” In Trees and Timber in the Anglo-Saxon World. Edited by Michael D. J. Bintley and Michael G. Shapland. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013, pages 144-57.

Cochran, Shannon Ferri. “The Plough’s the Thing: A New Solution to Old English Riddle 4 of the Exeter Book.” Journal of English and Germanic Philology, vol. 108, (2009), pages 301-9. (although this article deals with a different riddle, its discussion of the plough is relevant here)

Colgrave, Bertram. “Some Notes on Riddle 21.” Modern Language Review, vol. 32 (1937), pages 281-3.

Murphy, Patrick J. Unriddling the Exeter Riddles. University Park, PA: Pennsylvania State University Press, 2011.

Neville, Jennifer. “The Exeter Book Riddles’ Precarious Insights into Wooden Artefacts.” In Trees and Timber in the Anglo-Saxon World. Edited by Michael D. J. Bintley and Michael G. Shapland. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013, pages 122-38.

Williams, Edith Whitehurst. “Annals of the Poor: Folk Life in Old English Riddles.” Medieval Perspectives, vol. 3 (1988), pages 67-82.

Editorial Note:

The image of a different plough coulter was replaced and some text edited on 14 January 2021.

Tags: anglo saxon exeter book riddles old english solutions riddle 21

Related Posts:

Exeter Riddle 21