Exeter Riddle 43

MEGANCAVELL

Date: Tue 11 Aug 2015Matching Commentaries: Commentary for Exeter Riddle 43

This riddle comes to us from James Paz, Lecturer in early medieval English literature at the University of Manchester. He’s especially interested in ‘thing theory’ and medieval science. Take it away, James!

Ic wat indryhtne æþelum deorne

giest in geardum, þam se grimma ne mæg

hungor sceððan ne se hata þurst,

yldo ne adle. Gif him arlice

5 esne þenað, se þe agan sceal

on þam siðfate, hy gesunde æt ham

findað witode him wiste ond blisse,

cnosles unrim, care, gif se esne

his hlaforde hyreð yfle,

10 frean on fore. Ne wile forht wesan

broþor oþrum; him þæt bam sceðeð,

þonne hy from bearme begen hweorfað

anre magan ellorfuse,

moddor ond sweostor. Mon, se þe wille,

15 cyþe cynewordum hu se cuma hatte,

eðþa se esne, þe ic her ymb sprice.

I know a worthy one, treasured for nobility,

a guest in dwellings, whom grim hunger

cannot harm, nor hot thirst,

nor age, nor illness. If the servant

5 serves him honourably, he who must possess him

on the journey, they, safe at home,

will find afforded to them well-being and bliss;

an unspeakable progeny of sorrows shall be theirs,

if the servant obeys his lord and master

10 evilly on the way, if one brother will not fear

the other; that will harm them both,

when they turn away, eager to flee

from the breast of their only kinswoman,

mother and sister. Let he who holds the willpower

15 make known in fitting words what the guest is called,

or the servant I speak about here.

Notes:

This riddle appears on folios 112r-112v of The Exeter Book.

The above Old English text is based on this edition: Elliott van Kirk Dobbie and George Philip Krapp, eds, The Exeter Book, Anglo-Saxon Poetic Records 3 (New York: Columbia University Press, 1936), page 204.

Note that this edition numbers the text Riddle 41: Craig Williamson, ed., The Old English Riddles of the Exeter Book (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1977), page 96.

Tags: anglo saxon exeter book riddles old english solutions riddle 43

Related Posts:

Commentary for Exeter Riddle 43

Exeter Riddle 20

Exeter Riddle 49

>

>

Commentary for Exeter Riddle 42

MEGANCAVELL

Date: Thu 24 Sep 2015Matching Riddle: Exeter Riddle 42

We’re stepping back in time this week to revisit a riddle translation from last year! The fabulous Jennifer Neville (from Royal Holloway, University of London) shares some thoughts on early medieval chickens, sex and hall-life:

Riddle 42 is often classified as one of the double entendre riddles, but actually this is a single entendre riddle: when the text tells us, in its very first sentence, that it’s about sex (hæmedlac), it isn’t lying and it isn’t being metaphorical (although it does resort to metaphor a couple lines later). Unlike any other Old English text, this one does not cloak its depiction of sex in either euphemism or double-meaning. Everything is up front and open (undearnunga), public and outside (ute): if the man is up to the job, the lady will get her fill. This openness would make Riddle 42 even less prudish than most modern media, if it were about people, but, of course, it’s not. It’s about chickens.

Photo of a cock and hen (by Andrei Niemimäki) from Wikimedia Commons (license: CC BY-SA 2.0).

Chickens are interesting, and there are some things we could note here about early medieval husbandry. For example, the chickens are apparently running loose outside, not contained in a pen. The hen, at least, is not boring brown but proudly blonde (wlanc, hwitloc); perhaps some early medieval farmer has been practising selective breeding for colour. But the text doesn’t invite us to linger on those things. Rather, it wants us to think about sex.

We are used to hearing how negative early medieval writers were about sex, but here we see something different. Depending on how you look at them, the heanmode chickens are either "high-spirited" (frisky?) or "low-minded" (having their minds focused on worldly things?); regardless, their activity is not characterised as sinful. We are also familiar with the idea that sex should be only for the purposes of reproduction, but here there is no reference to offspring. Instead, the activity seems to take place purely for its own sake, and it is not a slothful leisure activity: the metaphor used to sum it up is weorc "work." Interestingly enough, most of the other twelve Old English riddles with (apparently) sexual content (Riddles 12, 20, 25, 37, 44, 45, 54, 61, 62, 63, 80, and 91) also use the idea of work to indicate the sexual act. Is this how the early English really felt about sex? Was it simply hard "work"? If so, they share the idea with us in the 21st century: the 2015 song by Fifth Harmony, "Work from Home", for example, explores the metaphor in great detail.

But the always fascinating topic of sex takes us only as far as line 5. At this point, we have to change gears and move into the world of the hall: the social centre of early English noble society, the place where kings presented gifts to their followers, where social drinking occurred, and where the speaker of this text offers to reveal the names of the sexy couple to the men drinking wine in the hall.[1] Again, this statement is tantalising: did the early English exchange riddles with each other in the hall, just as Symphosius did, centuries earlier, at his Saturnalian feast?[2] Before it was written down in the Exeter Book, was Riddle 42 part of an evening’s entertainment, an alternative to playing board games, singing a song in turn (as Caedmon refused to do), or listening to a professional singer?

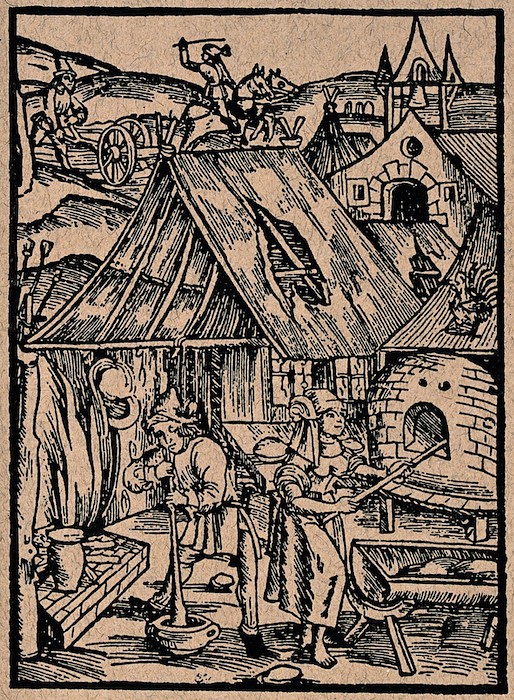

The hall at the place formerly known as Bede’s World. Photo courtesy of C.J.W. Brown.

Perhaps. But the only people who could solve this riddle would be those who could assemble and unscramble the letters named in the text, and most early medieval laymen were not literate. A normal gathering in the meadhall would have very few of those þe bec witan "who know books" (line 7a). Literacy was a technology reserved—for the most part—for the clergy. Once again, then, we need to change gears and move into another world, the world of the monastery and the scriptorium.

In the world of the scriptorium, there were plenty of people who could read ordinary letters, but in this text even that education wouldn’t be enough. The successful solver of the riddle would have to recognise the names of the run-stafas "runic letters" that have been woven into the metre and alliteration of this poem (Nyd, Æsc, Ac, and Hægl), assemble the collection of letters (some of which have to appear twice), and then rearrange them into not one but two words, hana "cock" and hæn "hen." The runic letters themselves don’t appear in the manuscript: a reader (or listener) would have to know that the words "need," "ash," "oak," and "hail" represent letters in order to understand what the text was asking him or her to do next.

This is what the runes would’ve looked like if they had been included (and rearranged to spell hana and hæn).

It’s thus unsurprising that the text taunts us: who here is smart enough to unlock the orþonc-bendas [3] "cunning bonds" that conceal the solution of this text? Not me: I’m very glad that Dietrich managed to work it out back in 1859. Otherwise, there would be no way to see the chickens. We could probably guess that they weren’t human beings having sex out in public, but, without the letters, their identity would most definitely not be undyrne "manifest, revealed, discovered."

Another puzzle remains, however: why are well-educated monks talking about fornicating fowls? And how did they get away with writing it down? The fact that we can’t answer those questions tells us that we still don’t know as much about the early English as we might have thought.

Notes:

[1] Or on the floor: flet literally means "floor," but it can be metonymy for the whole building.

[2] There’s a recent edition by T. J. Leary, or you can read Symphosius’ riddles (in Latin and in two published translations) on the LacusCurtius site.

[3] Tolkien uses this word, Orþonc, as the name of Saruman’s tower, which is unassailable by human or entish hands.

References and Suggested Reading:

Banham, Debby, and Rosamond Faith. Anglo-Saxon Farms and Farming. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2014.

Dewa, Roberta. “The Runic Riddles of the Exeter Book: Language Games and Anglo-Saxon Scholarship.” Nottingham Medieval Studies, vol. 39 (1995), pages 26-36.

Dietrich, F. “Die Rätsel des Exeterbuchs: Würdigung, Lösung und Herstellung.” Zeitschrift für deutsches Altertum, vol. 11 (1859), pages 448-490.

Lerer, Seth. “The Riddle and the Book: Exeter Book Riddle 42 in its Contexts.” Papers on Language and Literature, vol. 25 (1989), pages 3-18.

Nolan, Barbara, and Morton W. Bloomfield. “Beotword, Gilpcwidas, and the Gilphlæden Scop of Beowulf.” Journal of English and Germanic Philology, vol. 79 (1980), pages 499-516.

O’Donnell, Daniel Paul. Cædmon’s Hymn: A Multi-media Study, Edition and Archive. SEENET 8. Cambridge: Boydell & Brewer, 2006.

Salvador-Bello, Mercedes. “The Key to the Body: Unlocking Riddles 42-46.” In Naked Before God: Uncovering the Body in Anglo-Saxon England. Edited by Benjamin C. Withers and Jonathan Wilcox. Morgantown: West Virginia University Press, 2003, pages 60-96.

Smith, D. K. “Humor in Hiding: Laughter Between the Sheets in the Exeter Book Riddles.” In Humour in Anglo-Saxon England. Edited by Jonathan Wilcox. Cambridge: D. S. Brewer, 2000, pages 79-98.

Symons, Victoria. Runes and Roman Letters in Anglo-Saxon Manuscripts. Berlin: De Gruyter, 2016.

Tags: anglo saxon exeter book riddles old english solutions riddle 42 jennifer neville

Related Posts:

Commentary for Exeter Riddle 12

Commentary for Exeter Riddle 20

Commentary for Exeter Riddle 25

Commentary for Exeter Riddle 37

Commentary for Exeter Riddle 45

Commentary for Exeter Riddle 44

Commentary for Exeter Riddle 54

Commentary for Exeter Riddle 61

Commentary for Exeter Riddle 62

Commentary for Exeter Riddle 63

Commentary for Exeter Riddles 79 and 80

Commentary for Exeter Riddle 91