Date: Sun 19 Feb 2017

Matching Commentaries:

Commentary for Exeter Riddle 59

The following translation post is by Brett Roscoe, Assistant Professor at The King’s University in Alberta, and researcher of medieval wisdom literature. Take it away, Brett!

Original text:Ic seah in healle hring gyldenne

men sceawian, modum gleawe,

ferþþum frode. Friþospede bæd

god nergende gæste sinum

5 se þe wende wriþan; word æfter cwæð

hring on hyrede, hælend nemde

tillfremmendra. Him torhte in gemynd

his dryhtnes naman dumba brohte

ond in eagna gesihð, gif þæs æþelan

10 goldes tacen ongietan cuþe

ond dryhtnes dolg, don swa þæs beages

benne cwædon. Ne mæg þære bene

æniges monnes ungefullodre

godes ealdorburg gæst gesecan,

15 rodera ceastre. Ræde, se þe wille,

hu ðæs wrætlican wunda cwæden

hringes to hæleþum, þa he in healle wæs

wylted ond wended wloncra folmum.

Translation:I saw in the hall men behold

a golden ring, prudent in mind,

wise in spirit. He who turned the ring

asked for abundant peace for his spirit

5 from God the Saviour.(1) Then it spoke a word,

the ring in the gathering. It named the Healer

of those who do good. Clearly into memory

and into the sight of their eyes it brought, without words,

the Lord’s name, if one could perceive

10 the meaning of that noble, golden sign

and the wounds of the Lord, and do as the wounds

of the ring said. The prayer

of any man being unfulfilled,(2)

his soul cannot reach God’s royal city,

15 the fortress of the heavens. Let him who wishes explain

how the wounds of that curious ring

spoke to men, when, in the hall,

it was rolled and turned in the hands of the bold ones.

Click to show riddle solution?

Chalice

Notes: This riddle appears on folios 114v-115r of The Exeter Book.

The above Old English text is based on this edition: Elliott van Kirk Dobbie and George Philip Krapp, eds, The Exeter Book, Anglo-Saxon Poetic Records 3 (New York: Columbia University Press, 1936), pages 209-10.

Note that this edition numbers the text Riddle 57: Craig Williamson, ed., The Old English Riddles of the Exeter Book (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1977), pages 102-3.

Translation Notes:

(1) Here I follow Craig Williamson in translating god nergende as the object of the clause. Given the meaning of biddan (to pray, entreat, ask), I don’t think it likely that God is the subject. After all, who would God pray to?

(2) P. J. Cosijn suggests changing the manuscript ungefullodre to ungefullodra, translating it “of the unbaptized” (“Anglosaxonica. IV,” Beitrage, vol. 23 (1898), pages 109-30, at 130), the sense then being that the prayer of the unbaptized will not get them to heaven. The translation given here adopts the suggestion made by Frederick Tupper, Jr., The Riddles of the Exeter Book (Boston: Ginn, 1910), page 198.

Tags:

anglo saxon

exeter book

riddles

old english

solutions

riddle 59

Related Posts:

Exeter Riddle 42

Exeter Riddle 60

Exeter Riddle 67

Commentary for Exeter Riddle 56

MEGANCAVELL

Date: Fri 14 Oct 2016Matching Riddle: Exeter Riddle 56

I love Riddle 56 for many, many, many, many, many, many reasons, and I’ve been working on it on and off for about eight years, so BE PREPARED for me to unleash my inner geek. Disclaimer: this inner geek is possibly not quite as well hidden as I sometimes believe it to be. At least I’m self-aware.

So. Riddle 56. Why do I love it so much? Well, one of the reasons is that it’s very hard to solve without knowledge of early medieval material culture and craft. And the harder to solve ones are always more fun, non? The reason we need a bit of insight into early medieval craft is because the two most convincing solutions are Loom and Lathe.

“Tell us more, Megan,” I hear you cry! And I will. Oooooooh, I will.

Let’s start with Loom. One of the main types of weaving looms that early medieval folks used is called the warp-weighted loom (sounds ominous!). Here’s what it would’ve looked like.

Drawing of a loom from Montelius’s Civilisation of Sweden in Heathen Times, p. 160, via Roth’s Ancient Egyptian and Greek Looms, p. 34

Reconstructed loom on display at a Viking craft fair in York, 2010

This sort of loom would’ve stood upright and likely leaned against a wall. It had a large number of vertical threads – together referred to as the “warp” – dangling down to where they were tied in bunches. These threads would be tied not just to each other, but also to clay weights, which kept tension in the threads. Why so tense? Well, the weaver would be hard at work rapidly pulling and pushing the threads forward and backward by means of a horizontal bar partway down the front of the loom (known as a “heddle rod”). When one group of threads was pulled forward, the weaver would insert the horizontal (weft) threads. Then she’d push that lot back and insert the weft thread through a second batch of warp-threads. The tension stops the threads from getting all stuck together and ensures some easy peasy weaving (weavy?). The weights, by the way, often looked like doughnuts. I’m not even joking. Behold some doughnut-like weights!:

Photo of early medieval loom weights at Bedford Museum from Wikimedia Commons (public domain).

Doughnutty loom-weights aside, how does this sort of loom map onto the action of Riddle 56? Let’s start with the struggling creature: that appears to be the cloth mid-production. Its swinging and fixed feet seem to be the two separate groups of warp-threads (i.e. the ones pulled back and forth, and the ones that stay hanging at the back). The turning wood is probably a bar holding the finished fabric, which could be rotated to allow for weaving a longer piece of cloth than the actual size of the loom would normally allow.

There’s plenty of room to interpret this set-up as a bit torture-y, and John D. Niles has argued for this very assessment when analysing Old English descriptions of devices for hanging and stretching criminals (pages 61-84). And, of course, all those references to darts and bound wood that together inflict heaþoglemma (battle-wounds) and deopra dolga (deep gashes) in lines 3-4 of the riddle point quite clearly to a context of physical pain and punishment. This is helped along by the fact that the weaver would use a wooden or sometimes iron sword-shaped beater (or batten) to thwack the woven threads up and into place, as well as small picks to straighten out the occasional stubborn patch. Several surviving beaters were actually fashioned out of blunt swords or spear-heads (Walton Rogers, pages 33-4). So, there are definitely some violent undertones to textile-making.

Photo of a 9th-century sword beater from the Portable Antiquities Scheme (license CC BY 2.0).

In the Old Norse tradition, this violence is very noticeable. The poem Darraðarljóð (which can be found in Njáls saga) describes in great and gruesome detail a group of Valkyries weaving on a loom made from human body-parts. Likewise, Jómsvíkinga saga involves a dream sequence of the same sort. Their loom weights aren’t delicious doughnuts at all, but severed heads. Which is obviously gross.

All this means that violence is part and parcel of at least some northern medieval textile traditions. The question is, then, am I just a warped individual (get the pun? get it? get it?) or do I have a more nuanced reason for being attracted to Riddle 56, this most violent of riddles?

Well, I like to believe the latter is true. I personally think the combination of creative construction and violent destruction makes this riddle absolutely fascinating. Even if we don’t take the thing-being-made as a textile (some people have problems with that tree at the end of the poem, though it’s also been explained as a distaff standing near the loom, like in the drawing above), we’re certainly dealing with a riddle that describes a craft. And imagining a skilled craftsperson as a violent tormentor is, frankly, solid gold to anyone interested in ecocriticism (i.e. approaching literary texts by focusing on their representation of the natural world). Whether this is wool or flax twisted into a new shape – or whether it’s a completely different, wooden object – the raw material would once have been a part of the early medieval environment.

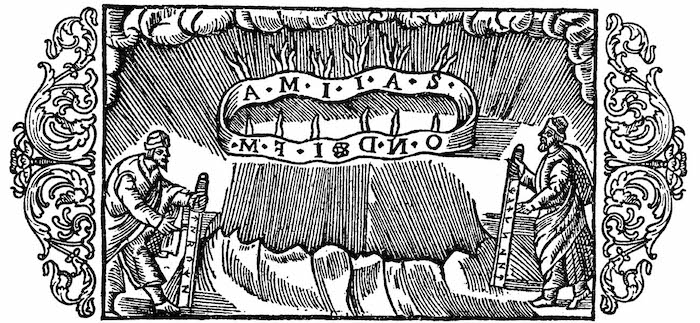

Which leads me to the second option for the riddle’s solution: Lathe. This is one that I become more and more convinced by each time I read the riddle. I know I’ve spent years talking about the poem in the light of textiles research, but a little part of me thinks that maybe, just maybe, the lathe reading works…even better. Here’s a video of a reconstructed pole lathe in process:

So, what we have here is a very clear case of one foot being fixed (i.e. the bit of the wooden pole stuck into the ground) and one swinging (i.e. the bit of the wooden pole that’s pulled and released by the foot treadle). Riddle 56’s reference to turning wood is especially apt, since a lathe is used to rotate wood while the operator shaves and grinds it into a particular shape (this is what’s going on behind the group of onlookers). A metal blade is also an essential part of the process, which explains all those battle-wounds. What do we make of that leafy tree in line 9, though? Well, this could potentially refer to the use of a fresh, green tree, which would be necessary for the lathe to keep its springiness.

And, finally, the creature that’s brought into the hall – well in this case it would be a bowl, cup or another dish made from wood. In the case of the loom, it would be a high-status textile, perhaps an item of clothing or a wall-hanging for decking out the hall. Either would be appropriate in the context of a feast for warriors. But, of course, a cup would add to the drinking party atmosphere in a pretty obvious way.

Unfortunately, I haven’t read many interpretations of this riddle that accept Lathe as the solution. Drawing on the passing suggestion of early riddle-scholars, Hans Pinsker and Waltraud Ziegler solve it this way in their German edition of the riddles, but they don’t go into a great detail (pages 277-8). This is too bad, because I think someone out there could make a real go of this. Maybe it could be you? If so, be sure to get in touch, eh?

References and Suggested Reading:

Cavell, Megan. “Looming Danger and Dangerous Looms: Violence and Weaving in Exeter Book Riddle 56.” Leeds Studies in English, vol. 42 (2011), pages 29-42. Online here.

Cavell, Megan. Weaving Words and Binding Bodies: The Poetics of Human Experience in Old English Literature. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2016.

Clegg Hyer, Maren. “Riddles of Anglo-Saxon England.” In Encyclopedia of Medieval Dress and Textiles of the British Isles, c. 450–1450. Edited by Gale R. Owen-Crocker, Elizabeth Coatsworth and Maria Hayward. Leiden: Brill, 2012.

Erhardt-Siebold, Erika von. “The Old English Loom Riddles.” In Philologica: The Malone Anniversary Studies. Edited by Thomas A. Kirkby and Henry Bosley Woolf. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins Press, 1949, pages 9-17.

Montelius, Oscar. Civilisation of Sweden in Heathen Times. Translated by Rev. F.H. Woods. 2nd ed. London: Macmillan, 1888.

Niles, John D. Old English Enigmatic Poems and the Play of the Texts. Turnhout: Brepols, 2006.

Pinsker, Hans, and Waltraud Ziegler, eds. Die altenglischen Rätsel des Exeterbuchs. Heidelberg: Winter, 1985.

Roth, H. Ling. Ancient Egyptian and Greek Looms. Halifax: Bankfield Museum, 1913. Online at Project Gutenberg.

Walton Rogers, Penelope. Cloth and Clothing in Early Anglo-Saxon England: AD 450–700. York: Council for British Archaeology, 2006.

More:

You may also enjoy this conversation with Sharif Adams about Riddle 56 and pole lathes/wood turning on our Youtube channel! Available here.

Tags: anglo saxon exeter book riddles old english solutions riddle 56

Related Posts:

Exeter Riddle 90

Commentary for Exeter Riddle 90