Date: Thu 13 Jul 2017

Matching Commentaries:

Commentary for Exeter Riddle 64

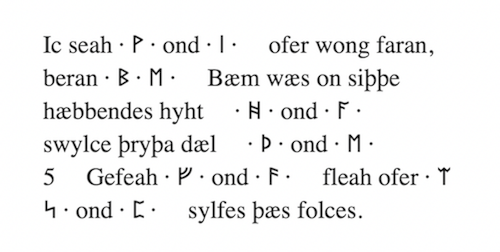

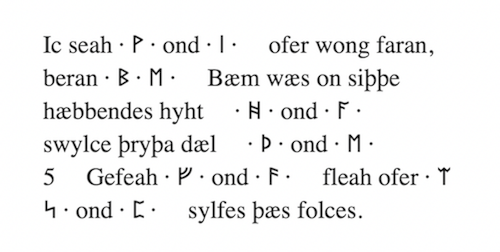

More runes, folks! If you can’t see the runes in the Old English riddle below, scroll down to the bottom of this post where you'll find a screenshot.

Original text:Ic seah · ᚹ · ond · ᛁ · ofer wong faran,

beran · ᛒ · ᛖ · Bæm wæs on siþþe

hæbbendes hyht · ᚻ · ond · ᚪ ·

swylce þryþa dæl · ᚦ · ond · ᛖ ·

5 Gefeah · ᚠ · ond · ᚫ · fleah ofer · ᛠ

ᛋ · ond · ᛈ · sylfes þæs folces.

Translation:I saw w and i travel over the plain,

carrying b . e . With both on that journey there was

the keeper’s joy: h and a,

also a share of the power: þ and e.

5 F and æ rejoiced, flew over the ea

s and p of the same people.

w and i = wicg (horse)

b and e = beorn (man)

h and a = hafoc (hawk)

þ and e = þegn (man)

f and æ = fælca (falcon)

ea and s and p = easpor? (water-track)

Click to show riddle solution?

man on horseback; falconry; ship; scribe; writing

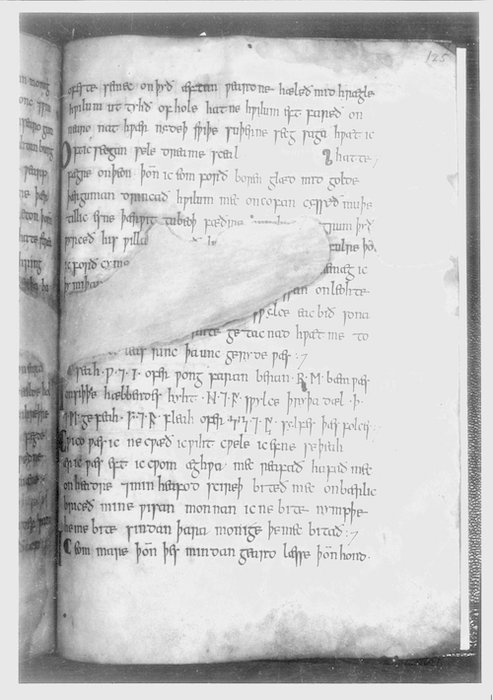

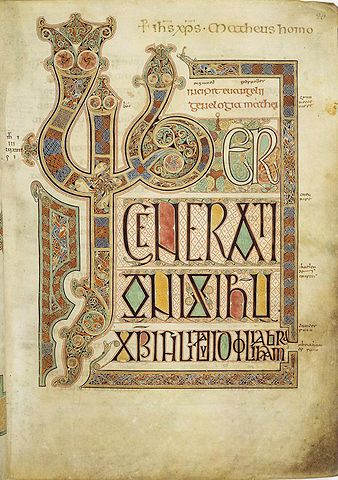

Notes: This riddle appears on folio 125r of The Exeter Book.

The above Old English text is based on this edition: Elliott van Kirk Dobbie and George Philip Krapp, eds, The Exeter Book, Anglo-Saxon Poetic Records 3 (New York: Columbia University Press, 1936), page 230.

Note that this edition numbers the text Riddle 62: Craig Williamson, ed., The Old English Riddles of the Exeter Book (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1977), page 105.

Screen shot for the runes:

Tags:

anglo saxon

exeter book

riddles

old english

solutions

riddle 64

Related Posts:

Exeter Riddle 19

Exeter Riddle 26

Exeter Riddle 7

Commentary for Exeter Riddle 61

MEGANCAVELL

Date: Mon 24 Apr 2017Matching Riddle: Exeter Riddle 61

Do you find early medieval men’s fashions particularly risqué? Well, whoever composed Riddle 61 sure seems to have done! That’s right, folks: it’s another riddle that’s chock-a-block full of double entendre.

The solution to Riddle 61 hasn’t proved as problematic as some of the other Exeter Book poems. Scholars have decided that it’s either a helmet (OE helm) or a shirt – though kirtle/tunic (OE cyrtel/tunece) are less anachronistic and more in line with early medieval style. You can see this sort of get-up in the following snippet from the Bayeux Tapestry:

And here’s a nice helmet for good measure:

It’s totally up to you whether you prefer a garment or helmet; I don’t have any strong opinions on this one. The long and the short of it is: whatever we’re talking about has to be an item with an opening that a man can put his head into or through. It has to come to rest on something hairy – could be his head, could be his chest. And it’s got to be small enough to store in a box, and not so heavy that the lady of the house couldn’t remove it by herself. I’m NOT saying that early medieval women couldn’t be strong and/or badass (have you ever tried setting up a loom? that’s some strenuous labour right there), but some of that later medieval plate armour looks cumbersome at best. But this isn’t what we’re talking about – I seem to have gone off topic already!

Anywho, it also sounds like the object in question is a tad on the valuable side, since it’s kept locked away and it claims to be frætwedne (adorned). This very brief reference to adornment is what reminds us we’re dealing with a constructed object instead of a sexual encounter. This was before vajazzling, after all. Though Sarah Higley suggests the text may be hinting at contraceptive items (and reminds us that we don’t know an awful lot about such things in early medieval England (pages 48-50)), I think it’s safe to say that it would be pretty impractical to adorn whatever sorts of things were used.

But enough about ancient prophylactics! (is a sentence I never thought I’d write) “Are there any other references to domestic scenes of husbands and wives and handing out garments in Old English?,” I hear you asking. Good question. There are indeed. There are indeed. The obvious passage is from the wisdom poem Maxims I (full translation here), which refers to a Frisian woman washing her husband’s clothes, giving him new ones and perhaps a little more than that (wink wink, nudge nudge). Why she has to be Frisian is beyond me (maybe just because it alliterates with flota (ship)?).

Here’s the passage I’m talking about:

leof wilcuma

Frysan wife, þonne flota stondeð;

biþ his ceol cumen ond hyre ceorl to ham,

agen ætgeofa, ond heo hine in laðaþ,

wæsceð his warig hrægl ond him syleþ wæde niwe,

liþ him on londe þæs his lufu bædeð. (lines 94b-9b)

(the dear one [is] welcome to his Frisian wife, when the ship stands; his boat has come home and her man, her own food-giver, and she calls him in, washes his dirty clothing and gives him new garments, gives him on land what his love requires.)

All I can think about when I read this poem is that this guy must smell horrible if he’s just coming back from a sea-voyage with little-to-no spare clothing. No wonder his wife is keen to get him into clean kit before the marital reunion commences.

But notice the similarities between this poem and Riddle 61 too: the husband-wife relationship, sexual implications, garment-giving. I wonder if his clothes are kept in a box too?

Speaking of which, the chest that holds the garment or helmet in Riddle 61 is also interesting because, as Edith Whitehurst Williams reminds us, it’s pretty impossible to apply it in a literal way to the bawdy reading of the poem (page 141). She reckons it’s “a metaphoric statement for the lady’s great modesty which is set aside only in the proper circumstance – when her lord commands” (page 141).

At this point you, like me, may be a bit annoyed with the unequal gender relations of this riddle. What’s all this commanding and bidding nonsense? I mean, of course we don’t want to impose an anachronistic view of women’s agency onto this very-very-very old poem, but still. If you do happen to find this aspect problematic, then I would suggest taking a look-see at Melanie Heyworth’s fascinating and insightful interpretation of this riddle. Hers is a nice and balanced, and fully contextualised reading of the poem (pages 179-80). Importantly, she points out that the woman gives/entrusts (the verb is sellan) her sexuality to her partner only gif (if) his ellen (strength/courage) is dohte (suitable/worthy). Now, I had translated line 7 as a reference to sexual potency – a crass sort of “if he can get it up and keep it going” sort of thing – but I quite like Heyworth’s version, since it suggests that both partners in this relationship are bringing something to the table. She’ll have sex with him only if he’s worthy, in other words. Admittedly, this comes across as a deeply conservative, heteronormative view of the world, but it was a very different world, so let’s try to keep our morals and theirs separate. Again, as Heyworth points out, Riddle 61 shows us an idealised marriage (page 180). In fact, she says its aim is to prescribe behaviour: “to urge its audience to similar conduct to that of the riddle-wife and her husband” (page 180).

Did everyone listen? Well, no, of course they didn’t. Would you need to prescribe behaviour if everyone was already on board?

We can find a great example of a woman who reputedly did NOT lock her sexuality away and entrust it only to her husband on the Bayeux Tapestry once again:

You may be confused about what’s going on in this picture. They’re fully clothed, so what’s all the bother about? Look closer. And look down and to the left. Behold the tiny naked man squatting at the bottom of this high-status textile! Most likely embroidered by English women during the transition from English to Norman rule, the Bayeux Tapestry depicts all manner of political and martial escapades relating to the famous conquest of 1066.

Now we don’t know the full story of this picture, partly because there’s no verb to tell us what’s going on: the Latin title just says Ubi unus clericus et Ælfgyva (Where a certain cleric and Ælfgifu). We also don’t know for certain who this panel depicts because the Old English name Ælfgifu, meaning “Elf-Gift,” was pretty common (for a good guess, check out J. L. Laynesmith’s article and podcast below). But even without that knowledge, we can say is that the picture seems to refer to some sort of scandal. That cleric probably shouldn’t be reaching through the archway to touch Ælfgifu’s face (is he caressing her? hitting her?). And the fact that the little naked man is mirroring the cleric, at least in his upper body and arms, strongly implies that the two are connected.

So, to tie this discussion up, I’d like to point out that it wasn’t just riddlers and scribes who revelled in double entendre. Early medieval women – in this case embroiderers – were also known to author some rather saucy stories. Intriguing ones too.

Bet you’ll never look at the Bayeux Tapestry with a straight face again.

References and Suggested Reading:

Heyworth, Melanie. “Perceptions of Marriage in Exeter Book Riddles 20 and 61.” Studia Neophilologica, vol. 79 (2007), pages 171-84.

Higley, Sarah L. “The Wanton Hand: Reading and Reaching into Grammars and Bodies in Old English Riddle 12.” In Naked Before God: Uncovering the Body in Anglo-Saxon England. Edited by Benjamin C. Withers and Jonathan Wilcox. Morgantown: West Virginia University Press, 2003, pages 29-59. Available online via Higley’s academia.edu page.

Laynesmith, J. L. “The Bayeux Tapestry: A Canterbury Tale.” History Today, vol. 62, issue 10 (Oct. 2012). http://www.historytoday.com/jl-laynesmith/bayeux-tapestry-canterbury-tale (podcast freely available here)

Whitehurst Williams, Edith. “What’s So New about the Sexual Revolution? Some Comments on Anglo-Saxon Attitudes toward Sexuality in Women Based on Four Exeter Book Riddles.” In New Readings on Women in Old English Literature. Edited by Helen Damico and Alexandra Hennessey Olsen. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1990, pages 137-45.

Tags: anglo saxon exeter book riddles old english solutions riddle 61

Related Posts:

Commentary for Exeter Riddle 43

Commentary for Exeter Riddle 77

Commentary for Exeter Riddle 82