Aldhelm Riddle 76: Melarius

ALEXANDRAREIDER

Date: Thu 14 Apr 2022Fausta fuit primo mundi nascentis origo,

Donec prostratus succumberet arte maligni;

Ex me tunc priscae processit causa ruinae,

Dulcia quae rudibus tradebam mala colonis.

En iterum mundo testor remeasse salutem,

Stipite de patulo dum penderet arbiter orbis

Et poenas lueret soboles veneranda Tonantis.

The beginning of the young world was happy at first,

Until the overthrown one succumbed to the deceit of the evil one;

The cause of the ancient ruin then came from me,

Who was giving out sweet apples to the uncultivated inhabitants.

Behold: I attest that well-being returned to the world again,

When the judge of the world was suspended from a stretched-out tree

And the venerable son of the Thundering God atoned for sins.

Notes:

This edition is based on Rudolf Ehwald, ed. Aldhelmi Opera Omnia. Monumenta Germaniae Historica, Auctores Antiquissimi, 15. Berlin: Weidmann, 1919, pages 59-150. Available online here.

Tags: riddles latin Aldhelm

Commentary for Exeter Riddle 77

MEGANCAVELL

Date: Thu 17 May 2018Matching Riddle: Exeter Riddle 77

GOODness gracious me. I’m clearly very out of practice, since this post took a veritable age and a half to write up. This is strange, in a way, since Riddle 77 is one of the least controversial riddles when it comes to solution-hunting: scholars are pretty much agreed that this watery tale of violent captivity, death and consumption concerns an oyster. But, even with this uncharacteristic scholarly agreement, there’s still lots to say about this and other early medieval oysters. Settle in and let us begin.

I should start by saying that – as with all the riddles toward the end of the Exeter Book – there’s some damage from the infamous hot poker here (not a metaphor…apparently, some very bad person put a literal hot poker on this fabulous manuscript, and they shall be forever damned in the eyes of medievalists). It’s strangely and gruesomely appropriate that the riddle ends with a reference to the solution’s uncooked-ness, just as the book itself heats up (sorry). But more on the riddle’s reference to cooking in a moment.

First, let’s think a little bit about the importance of environment. I’m thinking especially of the emphasis on sea and waves, which are represented here as a sundhelm (water-helm) (line 1b). This brilliant compound, when taken together with the reference to the ocean having concealed (wrugon) the oyster, reminds me of another truly fab word: heoloþhelm (helmet of invisibility). That’s right: the early English had a term for this…and not just them, since it exists in continental Old Saxon as well! Too. Good.

Anywho, a heoloþhelm is a particularly diabolic object. The devil sports this particular head-gear in Genesis B (line 444a) and in The Whale:

he him feorgbona

þurh sliþen searo siþþan weorþeð,

wloncum ond heanum, þe his willan her

firenum fremmað, mid þam he færinga,

heoloþhelme biþeaht, helle seceð,

goda geasne, grundleasne wylm

under mistglome, swa se micla hwæl,

se þe bisenceð sæliþende

eorlas ond yðmearas. (lines 41b-9a)

(he then becomes a murderer to them, through savage cunning, to the proud and to the lowly, those who sinfully perform his will here; with those, surrounded by a helmet of invisibility, deprived of virtues, he suddenly seeks out hell, the bottomless surge under the mist-gloom, just like the great whale, which sinks sea-travellers, men and their wave-horses.)

Okay so, there’s a link between helmets and the ocean and concealment and the devil in Old English poetry. Got it. But that’s not really what we’re dealing with here. This sundhelm (water-helm) is a protective and sustaining force for a creature with seemingly little agency when removed from the right environment. I like to imagine this poem being read out by David Attenborough on Blue Planet or similar. “The oyster, cleverly concealed below the depths, thinks it’s safe…until…” Alas, I couldn’t find any relevant clips from a nature doc online, but you may enjoy this somewhat-cheesily-narrated time-lapse video of oysters feeding:

The opening and closing of all those oysters’ shells is what we see in this riddle: Oft ic flode ongean / muð ontynde (Often I, facing the flood, opened my mouth) (lines 3b-4a). Karl Steel says these lines form a loop with the opening half-line: “Then, almost halfway through, with the “muð ontynde,” the opened mouth, it is as if the riddle reaches back to its first line, “sae mec feede,” the sea fed me, closing the loop on the opening to circulate the sea again and again through the oyster’s cavernous body. In the loop we have distinction without antagonism, difference disentangled from the struggle for recognition.” Nicely put, Karl.

The riddler sets up the oyster’s open mouth in opposition to human mouths…or, rather, the riddler shows how the oyster goes from having an open mouth into the mouth of another: Nu wile monna sum / min flæsc fretan (Now a certain person wishes to devour my flesh) (lines 4b-5a). This desire to devour is realised at the end of the (fragmentary) poem when the person iteð unsodene (eats [the oyster] uncooked) (line 8a). Several scholars have commented on the differences between the verbs fretan and etan (iteð is a form of this verb): the first is generally used of animals, and suggests a voracious sort of eating when it’s applied to humans, while etan is generally reserved for human use (Magennis, pages 74-76). Mercedes Salvador-Bello also chimes in here, emphasizing that fretan is often used “in literary passages that, regardless of animal or human context, explicitly or implicitly disapprove of the action that is being described” (pages 402-3). This is the sort of eating we should be judgey about, in other words.

Eating is, of course, one of many activities that invited judgement in the highly religious context of this riddle’s production. Most of the folks who write about this poem link it to another, called The Seasons for Fasting:

sona hie on mergan mæssan syngað

and forþegide, þurste gebæded,

æfter tæppere teoþ geond stræta.

Hwæt! Hi leaslice leogan ongynnað

and þone tæppere tyhtaþ gelome,

secgaþ þæt he synleas syllan mote

ostran to æte and æþele wyn

emb morgentyd, þæs þe me þingeð

þæt hund and wulf healdað þa ilcan

wisan on worulde and ne wigliað

hwæne hie to mose fon, mæða bedæled.

(Dobbie, page 104, lines 213-23)

(immediately in the morning they sing their masses and, consumed, compelled by thirst, go through the streets looking for a tavern-keeper. Behold! They begin to lie deceptively and pressure the tavern-keeper frequently, say that he can give them oysters to eat and good wine without sin at that time of the morning, so it seems to me that the hound and wolf have the same manner in the world and do not know when they may seize food, lacking moderation.)

This poem is especially incensed by the idea that a fasting priest might get away with gluttony because oysters weren’t prohibited during fasts (Salvador-Bello, page 405). Like fish, they could be eaten, but in moderation only. And they certainly shouldn’t be wolfed down, raw or otherwise.

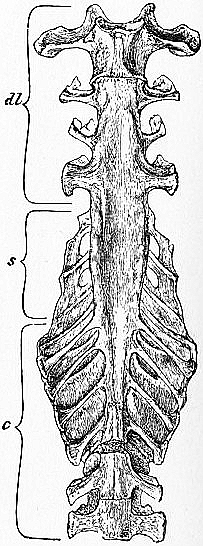

An oyster from the early 12th-century English bestiary in Oxford, Bodleian Library, MS. Laud Misc. 247, fol. 166v. Photo: Bodleian Libraries, University of Oxford, 2018.

We know that oysters were eaten in large quantities in early medieval England, and not just in coastal areas (Hagen, pages 169-70). They were so common, in fact, that monastic sign language (yes, monks had sign language…is this the coolest thing you’ve ever heard?) included a sign for oysters. The 11th-century Old English version of Monasteriales Indicia includes the following description:

Gif þu ostran habban wylle þonne clæm þu þine wynstran hand ðam gemete þe þu ostran on handa hæbbe and do mid sexe oððe mid fingre swylce þu ostran scenan wyll.

(If you want an oyster, then close your left hand, as if you had an oyster in your hand, and make with a knife or with your fingers as if you were going to open the oyster.) (Banham, pages 36-7, no. 72)

Here’s what it looks like in the manuscript:

Rules in monastic communities were particularly firm after the late tenth-century Benedictine reform, and sign language was an important way of keeping things running at times when monks weren’t allowed to speak. Debby Banham notes that the Old English version of Monasteriales Indicia in particular has very few signs for sea creatures: just one for fish in general, and one each for eels and oysters (Food and Drink, page 65). This suggests oysters were very common in the monastic refectory.

But despite their commonness, the oyster in this particular riddle is unique. Did you notice the violence of the oyster-shucking scene? This doesn’t seem to be driven by your run-of-the-mill “don’t be a glutton” rhetoric. And, in fact, the poem’s imagery is really quite strange: Riddle 77’s creature speaks of its fell (skin) and hyd (hide), using terms that are more familiarly associated with mammals. In fact, this riddle is the only case where either term refers to a shell. And there’s another link to a mammal when the oyster describes the seaxes orde (point of a knife) tearing the shell of sidan (from [its] side) (line 6). This reminds me of the end of Riddle 72, when the ox describes his stoic resignation in the face of the ploughman’s goad:

Oft mec isern scod

sare on sidan; ic swigade,

næfre meldade monna ængum

gif me ordstæpe egle wæron. (lines 15b-18)

(Often iron hurt me sorely in the side; I was silent, never accused any man if goad-pricks were painful to me.)

Heide Estes argues that the “foregrounding of violence to the animal as a prelude to human consumption in Riddle 77 […] suggests that the Anglo-Saxons had some sense that avoiding meat consumption was spiritually superior, though from the point of view of human asceticism rather than out of any concern for the animal” (page 122). In other words, monks ate meat rarely, not for ethical reasons, but because discipline and moderation brought them closer to their God. Given that the ox in Riddle 72 receives similarly violent treatment but is removed from the context of eating, I think we can push Heide’s argument further. The riddles show an understanding of and queasy discomfort with the pain that humans inflict upon other animals.

Bit of a depressing way to end a post, I know. Here, enjoy this bizarre infantilization of oysters from Alice and Wonderland by way of compensation:

References and Suggested Reading

Banham, Debby. Food and Drink in Anglo-Saxon England. Stroud: Tempus, 2004.

Banham, Debby, ed. and trans. Monasteriales Indicia: The Anglo-Saxon Sign Language. Middlesex: Anglo-Saxon Books, 1991.

Dobbie, Elliott van Kirk Dobbie, ed. The Anglo-Saxon Minor Poems. New York: Columbia University Press, 1942.

Estes, Heide. Anglo-Saxon Literary Landscapes: Ecotheory and the Environmental Imagination. Amsterdam: University of Amsterdam Press, 2017).

Hagen, Ann. Anglo-Saxon Food and Drink: Production, Processing, Distribution and Consumption. Hockwold cum Wilton: Anglo-Saxon Books, 2006.

Magennis, Hugh. Anglo-Saxon Appetites: Food and Drink and their Consumption in Old English and Related Literature. Dublin: Four Courts, 1999.

Salvador(-Bello), Mercedes. “The Oyster and the Crab: A Riddle Duo (nos. 77 and 78) in the Exeter Book.” Modern Philology, vol. 101, issue 3 (Feb. 2004), pages 400-19.

Steel, Karl. “Exeter Riddle 77: The Oyster.” Medieval Karl, 30 January 2017 https://medievalkarl.com/2017../../../riddles/post/exeter-riddle-77-the-oyster/

Tags: anglo saxon exeter book riddles old english solutions riddle 77

Related Posts:

Commentary for Exeter Riddle 72