Date: Thu 31 May 2018

Matching Commentaries:

Commentary for Exeter Riddle 84

Riddle 84 is translated by Beth Whalley, a PhD candidate at King’s College London. She works on (SOLUTION SPOILER ALERT!) water and waterways in early medieval culture and the contemporary arts.

Note that this riddle is another of the heavily damaged poems in the Exeter Book (so there are going to be A LOT of the ellipses below):

Original text:An wiht is on eorþan wundrum acenned,

hreoh ond reþe, hafað ryne strongne,

grimme grymetað ond be grunde fareð.

Modor is monigra mærra wihta.

5 Fæger ferende fundað æfre;

neol is nearograp. Nænig oþrum mæg

wlite ond wisan wordum gecyþan,

hu mislic biþ mægen þara cynna,

fyrn forðgesceaft; fæder ealle bewat

10 or ond ende, swylce an sunu,

mære meotudes bearn, þurh [……….]ed,

ond þæt hyhste mæge[…..]es gæ[….

………………] dyre cræft [.

………………………

15 .]onne hy aweorp[…………………….

..]þe ænig þara [……………………

……]fter ne mæg […………………

……..] oþer cynn eorþan […….

…………..] þon ær wæs

20 wlitig ond wynsum, [………..]

Biþ sio moddor mægene eacen,

wundrum bewreþed, wistum gehladen,

hordum gehroden, hæleþum dyre.

Mægen bið gemiclad, meaht gesweotlad,

25 wlite biþ geweorþad wuldornyttingum,

wynsum wuldorgimm wloncum getenge,

clængeorn bið ond cystig, cræfte eacen;

hio biþ eadgum leof, earmum getæse,

freolic, sellic; fromast ond swiþost,

30 gifrost ond grædgost grundbedd trideþ,

þæs þe under lyfte aloden wurde

ond ælda bearn eagum sawe,

swa þæt wuldor wifeð, worldbearna mægen,

þeah þe ferþum gleaw * * *(1)

35 mon mode snottor mengo wundra.

Hrusan bið heardra, hæleþum frodra,

geofum bið gearora, gimmum deorra;

worulde wlitigað, wæstmum tydreð,

firene dwæsceð,

40 oft utan beweorpeð anre þecene,

wundrum gewlitegad, geond werþeode,

þæt wafiað weras ofer eorþan,

þæt magon micle [………..]sceafte.

Biþ stanum bestreþed, stormum [……….

45 …………]len [………]timbred weall,

þrym[………………………..]ed,

hrusan hrineð, h[……………

………………]etenge,

oft searwum biþ [……………

50 ……………] deaðe ne feleð,

þeah þe […………………….

……]du hreren, hrif wundigen,

[……………………]risse.

Hordword onhlid, hæleþum ge[….

55 ……..]wreoh, wordum geopena,

hu mislic sy mægen þara cy[…]

Translation:On earth there is a creature born from wonders,

turbulent and fierce, she has a strong course.

She roars cruelly and proceeds across the depths.

She is mother to many great creatures,

5 the fair one travelling, she always hastens;

deep down is her tight grasp. No one may

with wise words make known her countenance

or the diversity of her kin,

the ancient creation. The father watches over all,

10 beginning and end, as the son,

glorious child of God through …

and that highest …

… secret skill …

…

15 … they cast away …

… any of them …

… may not after …

… other kindred … earth …

… which earlier was

20 beautiful and joyous, …

This mother is pregnant with virtue,

buoyed with wonders, laden with food,

bedecked with treasures, beloved by heroes.

Her strength is magnified, her might is revealed,

25 her form made worthy by her glorious uses.

This joyous glory-gem hastens to the bold.

She is eager for purity, bountiful, skill-swollen;

she is dear to the prosperous, helpful to the poor,

noble, extraordinary; boldest and strongest,

30 most covetous and greediest, she tramples on the foundation

of everything grown under the heavens

that men of old have seen.

So that she weaves glory, the power of earth’s children

as she is wise of mind * * *

35 a man more prudent of mind, a multitude of wonders.

She is harder than earth, older than heroes,

is more giving than gifts, more beloved than jewels;

she beautifies the world, produces plants,

extinguishes sin,

40 often from outside she casts a roof,

wondrously beautiful, throughout the nations,

that amazes men over the earth,

they are able greatly …

It is heaped up with stones, with storms

45 … timbered wall,

glory …

touches the earth, …

… near,

often is skillfully …

50 … nor feels death,

although …

… shaken, belly wounded

…

Un-close the word-hoard, for heroes …

55 …cover, open with words,

how diverse is power of those …

Click to show riddle solution?

Water

Notes: This riddle appears on folios 127v-128v of The Exeter Book.

The above Old English text is based on this edition: Elliott van Kirk Dobbie and George Philip Krapp, eds, The Exeter Book, Anglo-Saxon Poetic Records 3 (New York: Columbia University Press, 1936), pages 236-8.

Note that this edition numbers the text Riddle 80: Craig Williamson, ed., The Old English Riddles of the Exeter Book (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1977), pages 113-15.

Textual Note:

(1) Although there’s no problem with the manuscript at this point, the sense suggests that something is missing from the text here.

Tags:

anglo saxon

exeter book

riddles

old english

solutions

riddle 84

Related Posts:

Commentary for Exeter Riddle 84

Exeter Riddle 55

Exeter Riddle 56

Commentary for Exeter Riddle 82

VICTORIASYMONS

Date: Tue 30 Oct 2018Matching Riddle: Exeter Riddle 82

Where to start with Riddle 82? Barely 13 words survive of the original poem’s presumably 6 lines and yet, you may or may not be surprised to hear, we actually have a couple of competing solutions, both with suggestive evidence in their favour. Never let a lack of actual poem get in the way of a good theory.

Our first solution, courtesy of Holthausen, is “crab.” While there’s no direct reference to the sea in what’s left of our riddle, the greot (“grit,” line 2b) that the creature swallows could well refer to sand, as it does on the 8th-century Franks Casket.

The Franks Casket’s description of a whale stranding: “The [whale] grew sad where it swam on the grit.” Solid joke.

Photo (by Michel wal) from Wikimedia Commons (licence: CC BY-SA 3.0).

Crabs are, of course, notable for their many feet (line 4b).

Many feet. Photo of a land crab (by gailhampshire) from Wikimedia Commons (licence: CC BY 2.0)

Most significant, in support of this theory, is the line fell ne flæsc (“[neither] hide nor flesh,” line 4a). Crabs, of course, don’t have skin and they’re not “fleshy” in the same way as a mammal or fish.

“Cuddle?” Photo of a land crab (by gailhampshire) from Wikimedia Commons (licence: CC BY 2.0)

However. They may not be squishy on the outside, but crabs do have flesh and, as Craig Williamson points out (page 365), it was a bit of an early medieval delicacy. So that clue might not clinch the crab argument quite as convincingly as we could hope. Rather, Williamson suggests, the line is meant as a hint that our wiht is not a living creature at all. We’re back in the realm of the implement riddles, and the implement Williamson argues for is a harrow (pages 365-66).

Like this, only more medieval looking. Photo of a cultivator-harrow (by Rasbak) from Wikimedia Commons (licence: CC BY-SA 3.0)

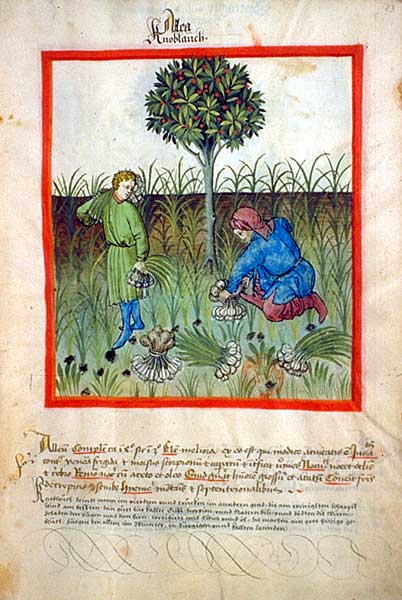

A harrow, for those not in the know, is a farming tool that’s dragged over a freshly-ploughed field to break up the smaller clods of earth in preparation for sowing. The earliest European depiction of a harrow is in the lower margins of the Bayeux Tapestry, and it’s an implement that may have been considered somewhat cutting-edge technology (ha!) in the period surrounding the Norman Conquest.

Back to our riddle. The swallowed grit in line 2 comes to the fore here – greot could be sand, but it can also mean regular old dirt. The multiple fotum that carry the creature suggest a larger tool such as a harrow (which would have been pulled by oxen or draught horses) rather than a smaller, hand-held rake.

“Ox or horse, you say?”. Image from the German Federal Archive via Wikimedia Commons (licence: CC BY-SA 3.0 de)

What seems to be an emphasis on the movement of the creature (gongende and gong[…], lines 2a and 4b) would fit with a tool whose primary function is to move up and down a field. There’s also, possibly, a parallel emphasis on the tool’s mouth (this is entirely my own speculation now!). I’ve translated mæl as “time”: mæla gehwæm (“each time,” line 6a) could refer either to the annually recurring season for ploughing, or to the more immediate repetition of the tool’s laps back and forth across a field.

Both kinds of repetition depicted rather neatly in this lovely scene from the Très Riches Heures du Duc de Berry (c. 1412-16). Image via Wikimedia Commons (licence: public domain)

But in other Old English texts, mæl can refer specifically to meal-time, or simply to meals. In Maxims I (also in the Exeter Book; full translation here), we have the sage observation:

Muþa gehwylc mete þearf, mæl sceoldon tidum gongan (Maxims I, line 110)

Every mouth needs meat, meals must come in time.

So, in our riddle, mæla gehwam might refer both to the movement of the harrow across the field and to the meal it makes of the ground as it goes. And it’s not hard to see how the design of the harrow could be suggestive of a gaping mouth, teeth and all, gobbling up the earth as it passes.

That is… probably all I have to say about Riddle 82. You’ll be glad to hear that next week’s riddle is substantially more fleshed out. Unlike Holthausen’s crab.

Photo of a land crab (by gailhampshire) from Wikimedia Commons (licence: CC BY 2.0)

References and Suggested Reading

Holthausen, Ferdinand. “Zu den altenglischen Ratseln.” Anglia Beiblatt 30 (1919), pages 50-55.

Williamson, Craig, ed. The Old English Riddles of the Exeter Book. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1977.

Tags: anglo saxon exeter book riddles old english solutions riddle 82

Related Posts:

Commentary for Exeter Riddle 88

Commentary for Exeter Riddle 77

Commentary for Exeter Riddle 81