Date: Tue 09 Sep 2014

Matching Commentaries:

Commentary for Exeter Riddle 28

Original text:Biþ foldan dæl fægre gegierwed

mid þy heardestan ond mid þy scearpestan

ond mid þy grymmestan gumena gestreona,

corfen, sworfen, cyrred, þyrred,

5 bunden, wunden, blæced, wæced,

frætwed, geatwed, feorran læded

to durum dryhta. Dream bið in innan

cwicra wihta, clengeð, lengeð,

þara þe ær lifgende longe hwile

10 wilna bruceð ond no wið spriceð,

ond þonne æfter deaþe deman onginneð,

meldan mislice. Micel is to hycganne

wisfæstum menn, hwæt seo wiht sy.

Translation:A portion of the earth is garnished beautifully

with the hardest and sharpest

and fiercest of treasures of men,

cut, filed, turned, dried,

5 bound, wound, bleached, weakened,

adorned, equipped, led far

to the doors of men. The joy of living beings

is within it, it remains, it lasts,

that which, while alive, enjoys itself

10 for a long time and does not speak against their wishes,

and then, after death, it begins to praise,

to declare in various ways. Great is it to think,

for wisdom-fast men, [to say] what the creature is.

Click to show riddle solution?

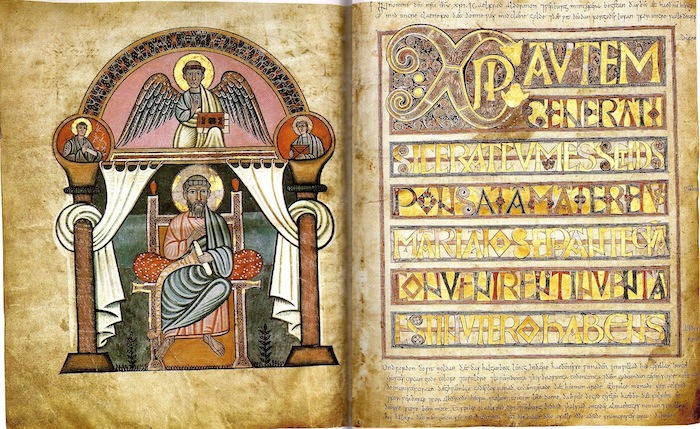

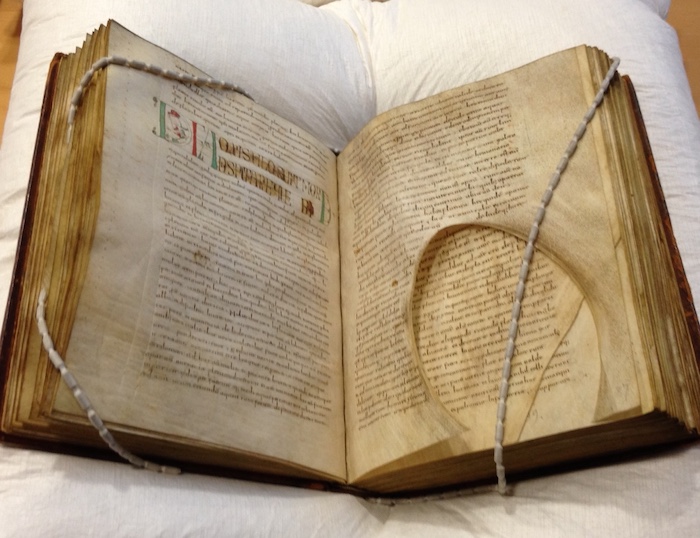

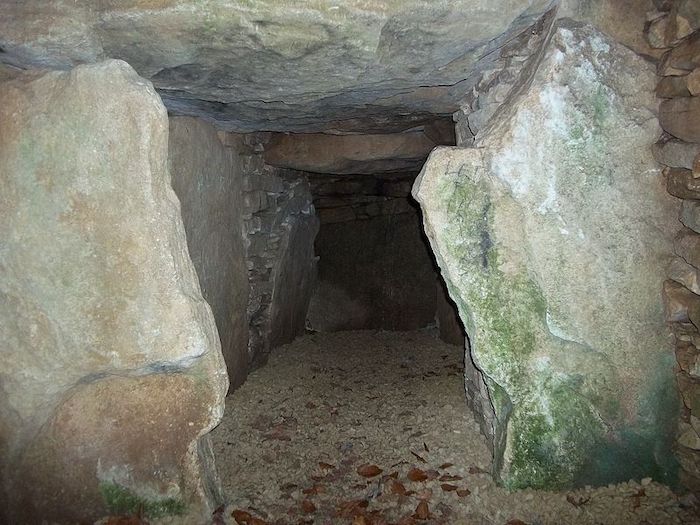

John Barleycorn, Wine cask, Beer, Ale, Mead, Harp, Stringed instrument, Tortoise lyre, Yew horn, Barrow, Trial of soul, Pattern-welded sword, Parchment, Biblical codex

Notes: This riddle appears on folio 107v of The Exeter Book.

The above Old English text is based on this edition: Elliott van Kirk Dobbie and George Philip Krapp, eds, The Exeter Book, Anglo-Saxon Poetic Records 3 (New York: Columbia University Press, 1936), pages 194-5.

Note that this edition numbers the text Riddle 26: Craig Williamson, ed., The Old English Riddles of the Exeter Book (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1977), page 84.

Tags:

anglo saxon

exeter book

riddles

old english

solutions

riddle 28

Related Posts:

Exeter Riddle 13

Exeter Riddle 26

Exeter Riddle 39

Commentary for Exeter Riddle 25

MEGANCAVELL

Date: Thu 03 Jul 2014Matching Riddle: Exeter Riddle 25

Just a little content warning to begin with. If you’ve already read Riddle 25’s translation, you’re probably aware that there’s some pretty obvious body humour going on in this poem. So prepare yourself to read the word “phallus” more times in one post than perhaps you would prefer.

Phallus.

(I did warn you)

So, Riddle 25, eh? What might the solution be? According to Donald K. Fry’s list of riddle solutions, this poem has been interpreted as: Hemp, Leek, Onion, Rosehip, Mustard and Phallus (p. 23). Onion, the Old English for which is cipe or cipeleac, has the most supporters.

This is what an onion looks like, for those of you who don’t know. Photo (author: Stephen Ausmus) from Wikimedia Commons.

The onion plant’s shape explains the riddle’s reference to a steapheah (literally, “steep-high”) staþol (foundation/base). I’m not entirely certain how you can have a “steep” foundation, although I’ve gone with editors Krapp and Dobbie here. This line would perhaps make a little more sense if we emend to stapol (pillar/shaft), as suggested by Andy Orchard (among others) in his forthcoming riddle edition for the Dumbarton Oaks Medieval Library. He notes that line 927a of Beowulf similarly reads staþole in the manuscript, where stapole would make more sense. So, yeah: a really steep…erect, even…shaft would make this poem’s clear phallic undertones (overtones?) even more pronounced. The verses immediately following this possible emendation refer to standing in a bed (bed of hair? bed of veggies? bed of sexcapades? or all of the above?) and to a lower roughness or shagginess that similarly signifies both the onion’s roots and hair in the nether regions. “Nether regions”: a term that is simultaneously hilarious and kind of gross. Alright, poet, we get it: vegetables are a bit rude (Blackadder, much?). So rude, in fact, that years ago one of my housemates taped a print-out of suggestively-shaped vegetables to her bedroom door in order to irritate her next-door neighbour. It worked.

Of course, all of the above descriptions could equally refer to other veggies. The leek is also a contender:

Leeks look a bit like green onions or shallots, but don’t taste as delicious. Fact. Photo (author: Björn König) from Wikimedia Commons.

But do leeks make you cry? (this is an honest question…I don’t really cook…ever…so I don’t know) Because the final half-line’s Wæt bið þæt eage (Wet will be that eye) seems to be playing with similarities between sex-related and non-sex-related wetness. According to the onion-reading, we’re dealing with actual eyes tearing up whilst chopping particularly aggressive vegetables (this is where the eye-wateringly strong mustard-interpretation comes in too). According to the phallus-reading…well (how to put this delicately?), we’re dealing with semen. I hope you can figure out precisely how that works for yourself.

This riddle also offers us a great deal to talk about beyond all the double entendre. For example, anyone who’s interested in gender and sexuality has a lot to sort through here. Yes, the suggestive, phallic solution relates to man parts, but the poem also hands us a pretty interesting picture of a sexually assertive woman. LOTS of people have written on this topic (see Davis, Hermann, Kim, Shaw and Whitehurst Williams, for example), so of course there’s disagreement about whether or not the poem judges the woman’s assertiveness – perhaps even aggressiveness, given how grabby those hands seem to be. It has been noted that she’s a ceorles dohtor (daughter of a churl/freeman), and so her aggressive approach may be linked to class prejudices (see Tanke).

I’ve also already spent some time thinking about the interesting hair-compound wundenlocc that the poem uses to describe the woman in the final line. I have a note on this, which you can access here (scroll down to my name). To sum that essay up: past scholarship can’t seem to agree on whether or not wundenlocc means “curly” or “braided” hair. A minor point, perhaps, but contentious enough to cause all sorts of divergent readings. However, given that Riddle 40 translates a Latin poem that describes the use of a curling iron with references to (ge)wundne loccas, I think “curly” hair is a better reading. I do note in that essay (p. 124, fn. 15) that Patrick Murphy (pp. 230-3) points out interesting parallels in the much later oral riddles collected by Archer Taylor (p. 196). Some of these riddles involve veggies with braided hair. Because of this and because of the grammatical ambiguity of these lines, Murphy argues that the wif wundenlocc is not just the grabby-handed woman, but also the onion itself. Now there’s some food for thought.

But who cares about hair? I’m sure some of you are thinking that. I mean, does it really matter? Well, yes, I think. Hair is culturally significant. In fact, Philip Shaw’s discussion of verbal parallels between Riddle 25 and Judith (a versification of the famous apocryphal story about a woman who decapitated the leader of an invading army) is concerned with precisely this. According to Shaw, hair is situated “within a rich intertextual matrix of ideas about Christianity versus heathenism” (p. 350). And such issues of religious identity are, of course, one of the big concerns of Old English literature. This puts hair (and onions, I guess) at the forefront of the entire field of study. Okay, that might be a slight exaggeration, but I do hope that it makes you think twice next time you see the smirking face of an actor whipping her/his hair about in a Pantene commercial. Cultural significance, people.

Phallus.

References and Suggested Reading:

If you want to know more about Anglo-Saxon approaches to sex, you should check out Christopher Monk’s work here.

Cavell, Megan. “Old English ‘Wundenlocc’ Hair in Context.” Medium Ævum, vol. 82 (2013), pages 119-25.

Davis, Glenn. “The Exeter Book Riddles and the Place of Sexual Idiom.” In Medieval Obscenities. Edited by Nicola McDonald. York: York Medieval Press, 2006, pages 39-54.

Fry, Donald K. “Exeter Book Riddle Solutions.” Old English Newsletter, vol. 15, issue 1 (1981), pages 22-33.

Hermann, John P. Allegories of War: Language and Violence in Old English Poetry. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1989 (page 191 onward).

Kim, Susan. “Bloody Signs: Circumcision and Pregnancy in the Old English Judith.” Exemplaria, vol. 11, issue 2 (Fall 1999), pages 285-307.

Murphy, Patrick J. Unriddling the Exeter Riddles. University Park, PA: Penn State University Press, 2011, pages 203, 222, and 230-3.

Shaw, Philip. “Hair and Heathens: Picturing Pagans and the Carolingian Connection in the Exeter Book and Beowulf-Manuscript.” In Texts and Identities in the Early Middle Ages. Edited by Richard Corradini, Rob Meens, Christina Pössel and Philip Shaw. Forschungen zur Geschichte des Mittelalters, vol. 12 (Vienna: Österreichischen Akademie der Wissenschaften, 2006), pages 345-57.

Tanke, John W. “Wonfeax wale: Ideology and Figuration in the Sexual Riddles of the Exeter Book.” In Class and Gender in Early English Literature: Intersections. Edited by Britton J. Harwood and Gillian R. Overing. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1994, pages 21-42.

Taylor, Archer. English Riddles from Oral Tradition. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1951.

Whitehurst Williams, Edith. “What’s so New about the Sexual Revolution? Some Comments on Anglo-Saxon Attitudes toward Sexuality in Women based on Four Exeter Book Riddles.” Texas Quarterly, vol. 18, issue 2 (1975), pages 46–55 (reprinted in New Readings on Women in Old English Literature, edited by Helen Damico and Alexandra Hennessey Olsen. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1990, pages 137-45).

Tags: anglo saxon exeter book riddles old english solutions riddle 25

Related Posts:

Commentary for Exeter Riddle 43

Commentary for Exeter Riddle 61

Commentary for Exeter Riddle 32