Date: Mon 13 Oct 2014

Matching Commentaries:

Commentary for Exeter Riddles 30a and b

We have all sorts of treats for you today, so I hope you’re glued to your seats and screens. Not literally…that would be more than a little weird. First of all, we have a double riddle. That sounds amazing, I know, but it also requires explanation. Up until now, the riddles have all appeared one after another in the Exeter Book, but there are two versions of Riddle 30 — one here, and one later in the manuscript, following Homiletic Fragment II (absolutely scintillating name…). We’ve decided to do both versions of Riddle 30 at the same time, and for these we have a guest translator. Pirkko Koppinen completed her PhD at Royal Holloway, University of London, where she is currently a visiting lecturer. She also brings to us an expertise in museum and heritage studies, as well as Finnish. Pirkko has generously offered us not only English translations of both Riddle 30a and b, but also Finnish ones. Surely this can be described as nothing short of a cornucopia of riddle-fun. Take it away, Pirkko!

Original text:Riddle 30a

Ic eom legbysig, lace mid winde,

bewunden mid wuldre, wedre gesomnad,

fus forðweges, fyre gebysgad,

bearu blowende, byrnende gled.

5 Ful oft mec gesiþas sendað æfter hondum,

þæt mec weras ond wif wlonce cyssað.

Þonne ic mec onhæbbe, ond hi onhnigaþ to me

monige mid miltse, þær ic monnum sceal

ycan upcyme eadignesse.

Riddle 30b

Ic eom ligbysig, lace mid winde,

w[……………..]dre gesomnad,

fus forðweges, fyre gemylted,

b[ . ] blowende, byrnende gled.

5 Ful oft mec gesiþas sendað æfter hondum,

þær mec weras ond wif wlonce gecyssað.

Þonne ic mec onhæbbe, hi onhnigað to me,

modge miltsum, swa ic mongum sceal

ycan upcyme eadignesse.

Translation:Riddle 30a

I am busy with fire, fight with the wind,

wound around with glory, united with storm,

eager for the journey, agitated by fire;

[I am] a blooming grove, a burning ember.

5 Very often companions send me from hand to hand

so that proud men and women kiss me.

When I exalt myself and they bow to me,

many with humility, there I shall

bring increasing happiness to humans.

A free rendering of Riddle 30a into Finnish:

Minä ahkeroin tulen kanssa, leikin tuulella. [Minä olen] kietoutunut kunniaan, yhdistetty myrskyyn. [Olen] innokas lähtemään, liekillä kiihotettu. [Olen] kukoistava lehto, hehkuva hiillos. Kumppanit kierrättävät minua usein kädestä käteen siellä, missä korskeat miehet ja naiset suutelevat minua. Kun ylistän itseäni ja he, monet, nöyränä kumartavat minua, siellä minä tuon karttuvaa riemua ihmisille.

Riddle 30b

I am busy with fire, fight with the wind,

[…] united […],

eager for the journey, consumed by fire;

[I am] a blooming […], a burning ember.

5 Very often companions send me from hand to hand

where proud men and women kiss me.

When I exalt myself, high-spirited [ones]

bow to me with humility, in this way I shall

bring increasing happiness to many.

A free rendering of Riddle 30b into Finnish:

Minä ahkeroin tulen kanssa. Leikin tuulella. […] on kiedottu […]. [Olen] innokas lähtemään, tulessa tuhottu. [Olen] kukoistava […], hehkuva hiillos. Useasti kumppanit kierrättävät minua kädestä käteen siellä, missä korskeat miehet ja naiset suutelevat minua. Kun ylistän itseäni, ja he, ylväät, nöyränä kumartavat minua. Täten minä tuon karttuvaa riemua monille.

Click to show riddle solution?

Beam, Cross, Wood, Tree, Snowflake

Notes: This riddle appears on folios 108r and 122v of The Exeter Book.

The above Old English text is based on this edition: Elliott van Kirk Dobbie and George Philip Krapp, eds, The Exeter Book, Anglo-Saxon Poetic Records 3 (New York: Columbia University Press, 1936), pages 195-6 and 224-5.

Note that this edition numbers the text Riddle 28a and b: Craig Williamson, ed., The Old English Riddles of the Exeter Book (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1977), pages 85-6.

Textual Notes

The damaged words in Riddle 30b are marked with square brackets. I have highlighted the differences in the two texts in bold and translated accordingly. Line 7b in Riddle 30a reads on hin gað (which is a nonsensical form) in the manuscript and is emended to onhnigað by using the text of Riddle 30b (line 7b); see Krapp and Dobbie, page 338.

Tags:

anglo saxon

exeter book

riddles

old english

solutions

riddle 30

Related Posts:

A Brief Introduction to Riddles

Commentary for Exeter Riddle 43

Commentary for Exeter Riddle 86

Commentary for Exeter Riddle 29

MEGANCAVELL

Date: Tue 07 Oct 2014Matching Riddle: Exeter Riddle 29

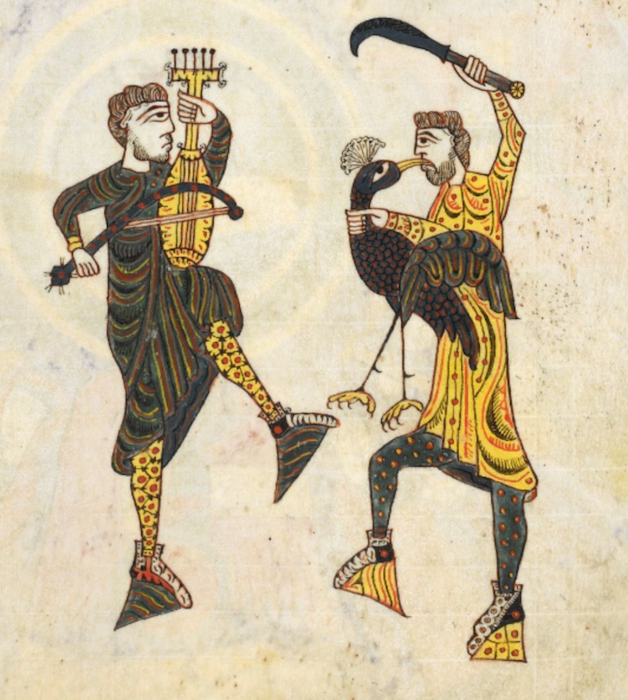

Did you get this one without looking at the solution? It’s usually seen as one of the more obvious Riddles: the sun and the moon. And because it is so obvious, people haven’t really found very much else to say about it. But let’s run through it quickly: The “creature” carrying the booty “between its horns” is the waxing moon – the image below nicely shows the “horns” and the space “between” them that gets filled up with light as the moon grows fuller. Then the sun comes over the horizon (if that’s what we think “over the roof/top of the wall” means) and slowly “takes back” its light, until the waning moon disappears into the new moon – nobody knows where it went, as in the final two lines. That’s it, then – done, dusted, let’s head off to the pub, shall we (maybe not this one though)?

Photo (by Christine Matthews) from the Wikimedia Commons (licence: CC BY-SA 2.0).

But I know you’ve got used to much more in-depth analysis here at The Riddle Ages, so let’s see what we can do, shall we? Sticking for the moment with the natural phenomena, what are we to make of the dew and dust in the final few lines of the poem? There was a medieval belief that the moon produced dew, so let’s run with that. But how can there be dew and dust at the same time? Wouldn’t you have to have some sort of muddy grit? Well, yes – nobody has really found a good explanation for this yet but maybe we shouldn’t take the riddle quite so literally here and just enjoy the nice balance between the rising dust and the falling dew.

However, as you may have come to expect by now, the riddle can also be read on an allegorical level: some scholars have argued that it also describes the Harrowing of Hell, where Christ overcomes Satan to rescue or liberate (ahreddan) condemned souls from hell and lead them into heaven. The sun is often a symbol for Christ in early medieval writings (and think back for example to Riddle 6). Occasionally we find the moon standing in for Satan (but not because of the horns!) and so the struggle described in the riddle can be seen as a battle between those two. The story of Satan’s uprising against God and his downfall was very popular in early medieval England and the language used in the riddle may give us a further hint here: like the moon in the riddle, Satan tries to build a home for himself in heaven, with the help of ill-gotten gains, and is eventually driven out into exile by God. There’s a nice play on the ham here: the moon is trying to establish a ham (in line 4) but is driven out of there into a different ham (line 9): his real home, the exile outside of heaven.

So even in riddles where everyone agrees on the solution, there’s usually still a lot more to be said if you get into it. That’s why the riddles are brilliant!

References and Suggested Reading:

Joyce, John H. “Natural Process in Exeter Book Riddle #29.” Annuale Mediaevale, vol. 14 (1974), pages 5-13.

Murphy, Patrick J. Unriddling the Exeter Riddles. University Park, PA: Penn State University Press, 2011, pages 123-39.

Whitman, Frank H. “The Christian Background to Two Riddle Motifs.” Studia Neophilologica, vol. 41 (1969), pages 93-8.

Tags: anglo saxon exeter book riddles old english solutions riddle 29

Related Posts:

Commentary for Exeter Riddle 6