Date: Mon 13 Oct 2014

Matching Commentaries:

Commentary for Exeter Riddles 30a and b

We have all sorts of treats for you today, so I hope you’re glued to your seats and screens. Not literally…that would be more than a little weird. First of all, we have a double riddle. That sounds amazing, I know, but it also requires explanation. Up until now, the riddles have all appeared one after another in the Exeter Book, but there are two versions of Riddle 30 — one here, and one later in the manuscript, following Homiletic Fragment II (absolutely scintillating name…). We’ve decided to do both versions of Riddle 30 at the same time, and for these we have a guest translator. Pirkko Koppinen completed her PhD at Royal Holloway, University of London, where she is currently a visiting lecturer. She also brings to us an expertise in museum and heritage studies, as well as Finnish. Pirkko has generously offered us not only English translations of both Riddle 30a and b, but also Finnish ones. Surely this can be described as nothing short of a cornucopia of riddle-fun. Take it away, Pirkko!

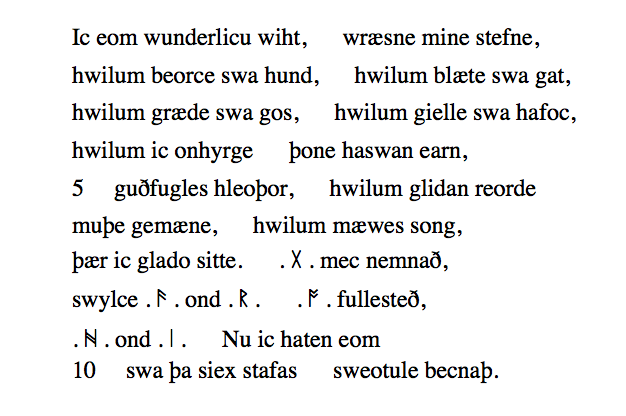

Original text:Riddle 30a

Ic eom legbysig, lace mid winde,

bewunden mid wuldre, wedre gesomnad,

fus forðweges, fyre gebysgad,

bearu blowende, byrnende gled.

5 Ful oft mec gesiþas sendað æfter hondum,

þæt mec weras ond wif wlonce cyssað.

Þonne ic mec onhæbbe, ond hi onhnigaþ to me

monige mid miltse, þær ic monnum sceal

ycan upcyme eadignesse.

Riddle 30b

Ic eom ligbysig, lace mid winde,

w[……………..]dre gesomnad,

fus forðweges, fyre gemylted,

b[ . ] blowende, byrnende gled.

5 Ful oft mec gesiþas sendað æfter hondum,

þær mec weras ond wif wlonce gecyssað.

Þonne ic mec onhæbbe, hi onhnigað to me,

modge miltsum, swa ic mongum sceal

ycan upcyme eadignesse.

Translation:Riddle 30a

I am busy with fire, fight with the wind,

wound around with glory, united with storm,

eager for the journey, agitated by fire;

[I am] a blooming grove, a burning ember.

5 Very often companions send me from hand to hand

so that proud men and women kiss me.

When I exalt myself and they bow to me,

many with humility, there I shall

bring increasing happiness to humans.

A free rendering of Riddle 30a into Finnish:

Minä ahkeroin tulen kanssa, leikin tuulella. [Minä olen] kietoutunut kunniaan, yhdistetty myrskyyn. [Olen] innokas lähtemään, liekillä kiihotettu. [Olen] kukoistava lehto, hehkuva hiillos. Kumppanit kierrättävät minua usein kädestä käteen siellä, missä korskeat miehet ja naiset suutelevat minua. Kun ylistän itseäni ja he, monet, nöyränä kumartavat minua, siellä minä tuon karttuvaa riemua ihmisille.

Riddle 30b

I am busy with fire, fight with the wind,

[…] united […],

eager for the journey, consumed by fire;

[I am] a blooming […], a burning ember.

5 Very often companions send me from hand to hand

where proud men and women kiss me.

When I exalt myself, high-spirited [ones]

bow to me with humility, in this way I shall

bring increasing happiness to many.

A free rendering of Riddle 30b into Finnish:

Minä ahkeroin tulen kanssa. Leikin tuulella. […] on kiedottu […]. [Olen] innokas lähtemään, tulessa tuhottu. [Olen] kukoistava […], hehkuva hiillos. Useasti kumppanit kierrättävät minua kädestä käteen siellä, missä korskeat miehet ja naiset suutelevat minua. Kun ylistän itseäni, ja he, ylväät, nöyränä kumartavat minua. Täten minä tuon karttuvaa riemua monille.

Click to show riddle solution?

Beam, Cross, Wood, Tree, Snowflake

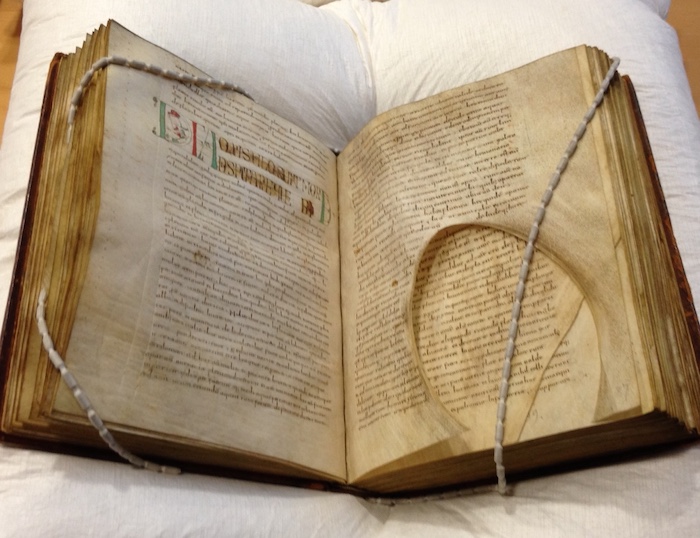

Notes: This riddle appears on folios 108r and 122v of The Exeter Book.

The above Old English text is based on this edition: Elliott van Kirk Dobbie and George Philip Krapp, eds, The Exeter Book, Anglo-Saxon Poetic Records 3 (New York: Columbia University Press, 1936), pages 195-6 and 224-5.

Note that this edition numbers the text Riddle 28a and b: Craig Williamson, ed., The Old English Riddles of the Exeter Book (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1977), pages 85-6.

Textual Notes

The damaged words in Riddle 30b are marked with square brackets. I have highlighted the differences in the two texts in bold and translated accordingly. Line 7b in Riddle 30a reads on hin gað (which is a nonsensical form) in the manuscript and is emended to onhnigað by using the text of Riddle 30b (line 7b); see Krapp and Dobbie, page 338.

Tags:

anglo saxon

exeter book

riddles

old english

solutions

riddle 30

Related Posts:

A Brief Introduction to Riddles

Commentary for Exeter Riddle 43

Commentary for Exeter Riddle 86

Commentary for Exeter Riddle 21

MEGANCAVELL

Date: Sun 06 Apr 2014Matching Riddle: Exeter Riddle 21

Boy, we sure are plowing through these riddles, aren’t we? Get it? Get it? If not, you must have forgotten the solution to Riddle 21: plough or plow (depending on how you prefer to spell)! If you prefer to spell like someone from early medieval England, then you’d be spelling it sulh. There isn’t a great deal of debate over this riddle’s solution, which – I have to say – is kind of obvious. So instead of scholarly debate, I’m going to impress you with pictures. And also details and such-like.

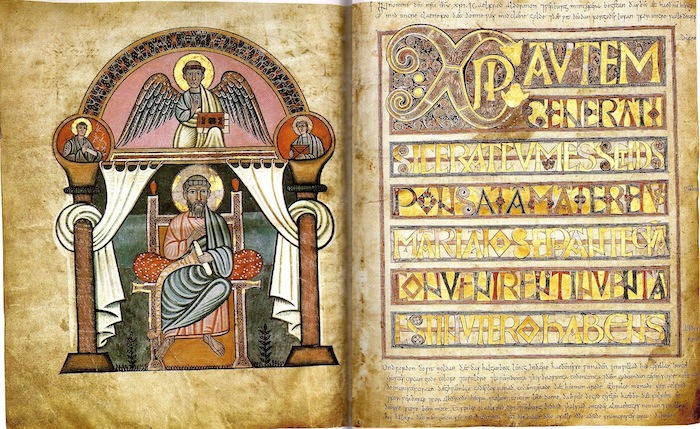

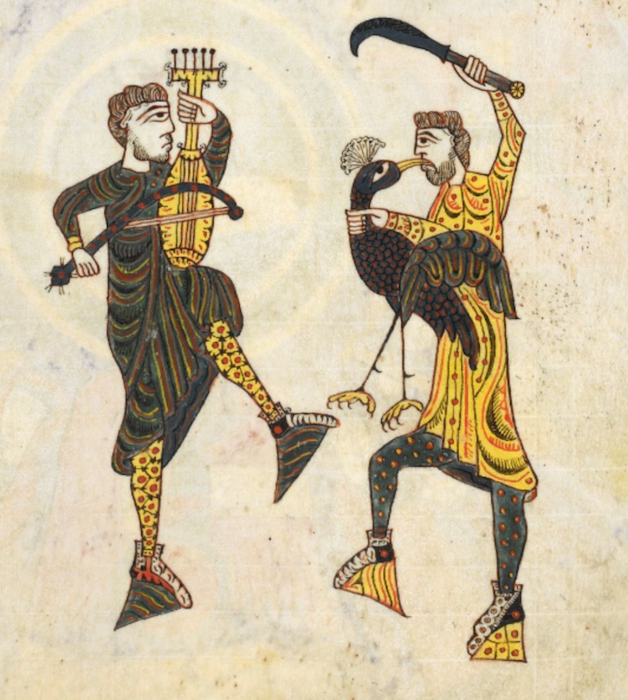

Here is a reproduction of a plough drawing in an eleventh-century calendar now housed in the British Library (Cotton MS Tiberius B V/1, folio 3r):

From The New Gresham Encyclopedia, available free online at Project Gutenberg. The original, in all its colourful glory, is digitized here.

The (quite lumpy-looking, though nonetheless smiley) team of oxen is nicely visible here, as are the various parts of the plough. These include the share (the bit that breaks up the earth) and the coulter (the bit that makes a groove for sowing seeds), which may be represented in the poem as the creature’s neb (nose), as well as the weapon that pierces the plough’s head (similar to the orþoncpil (skillful spear) driven through its back). Here’s a picture of an early medieval iron coulter from North Lincolnshire Museum:

Image from the Portable Antiquities Scheme (licence: CC BY-SA).

In addition to the specifics of actual ploughing (i.e. the description of the object laying horizontally and being pushed along, the sowing of seeds, the churning up of earth to make a path and the elements that pierce the object’s body), this poem provides useful information on an important aspect of the early medieval world: slavery. Whether born into it, taken in warfare or punished for criminal activity, slaves were common in this period. Despite the widespread nature of slavery at this time, few slaves are given voice in Old English literature, which is one of the reasons Riddle 21 is such an important text.

“Why the plough?” you might ask. “Surely there are all sorts of objects and animals that could have been chosen to represent an enslaved person in early medieval England.” That’s true, of course, and there are other riddles that give evidence of slavery. However, the fact that ploughing was a common role for slaves (according to the Domesday Book) goes some way to explaining the riddler’s choice. The unhappy conditions of slavery are also expounded in the Colloquy that Ælfric of Eynsham wrote in order to help his students learn Latin. It introduces a variety of figures who are quizzed about their roles and responsibilities. In a particularly empathetic passage, the enslaved ploughman cries: O! O! magnus labor. etiam, magnus labor est, quia non sum liber in Latin, or Hig! Hig! micel gedeorf ys hyt. / Geleof, micel gedeorf hit ys, forþam ic neom freoh (34-5) (Oh! Oh! The labour is great. Yes, the labour is great, because I am not free) in Old English (at page 21, lines 34-5). This is a rare example of a slave having a voice at all, let alone one that demands empathy.

Dexter cattle at Bede’s World in Jarrow. Photo courtesy of C.J.W. Brown.

Riddle 21 is another example of a metaphorical slave describing her/his condition. In fact, this riddle provides us with information about the type of slave the poem depicts: this slave has been brought from the forest, bound and borne into the settlement (brungen of bearwe, bunden cræfte, / wegen on wægne). The implication of the half-line har holtes feond (the old foe of the forest) is that the ploughman or ox responsible for clearing the land takes slaves during battle, an idea driven home by the weapon-imagery toward the end of the poem.

This context of slavery makes the poem’s innuendo pretty disturbing, if you ask me (Murphy talks about this innuendo at pages 175-6 of his book, cited below). All the riddle’s references to the prone speaker being aggressively pushed by its master (class/status implications are also clear when the poem refers to the plough’s hlaford (lord) twice) who sows seed are brought to a head by the final lines’ description of being served from behind. It doesn’t take an especially pervy imagination to see how this could be read sexually, particularly given the connotations of “plowing” in Modern English. Of course, the reference to the speaker’s steort (tail) and tearing teeth (ic toþum tere) may introduce a bestial element that only makes things worse.

All in all, Riddle 21 presents us with a creature forced to perform hard labour for its captor. I’d like to think that this image is a sympathetic one, but the introduction of innuendo may imply that the enslaved victim is the butt of the joke. Or maybe the fact that we’re dealing with an object rather than a person can ease our discomfort. I haven’t decided yet.

References and Suggested Reading:

Ælfric of Eynsham. Ælfric’s Colloquy. Edited by G. N. Garmonsway. London: Methuen, 1939.

Bintley, Michael D. J. “Brungen of Bearwe: Ploughing Common Furrows in Riddle 21, The Dream of the Rood, and the Æcerbot Charm.” In Trees and Timber in the Anglo-Saxon World. Edited by Michael D. J. Bintley and Michael G. Shapland. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013, pages 144-57.

Cochran, Shannon Ferri. “The Plough’s the Thing: A New Solution to Old English Riddle 4 of the Exeter Book.” Journal of English and Germanic Philology, vol. 108, (2009), pages 301-9. (although this article deals with a different riddle, its discussion of the plough is relevant here)

Colgrave, Bertram. “Some Notes on Riddle 21.” Modern Language Review, vol. 32 (1937), pages 281-3.

Murphy, Patrick J. Unriddling the Exeter Riddles. University Park, PA: Pennsylvania State University Press, 2011.

Neville, Jennifer. “The Exeter Book Riddles’ Precarious Insights into Wooden Artefacts.” In Trees and Timber in the Anglo-Saxon World. Edited by Michael D. J. Bintley and Michael G. Shapland. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013, pages 122-38.

Williams, Edith Whitehurst. “Annals of the Poor: Folk Life in Old English Riddles.” Medieval Perspectives, vol. 3 (1988), pages 67-82.

Editorial Note:

The image of a different plough coulter was replaced and some text edited on 14 January 2021.

Tags: anglo saxon exeter book riddles old english solutions riddle 21

Related Posts:

Exeter Riddle 21