Date: Thu 19 Dec 2019

Matching Commentaries:

Commentary for Exeter Riddle 88

We have a guest translator for this riddle: the one and only

Denis Ferhatović. Denis is associate professor of English at Connecticut College and an enthusiast when it comes to poetic creativity. He has brought some of this creativity to the below translation, which I hope you enjoy reading as much as I have!

Original text:

Ic weox þær ic s[……………………

……..]ond sumor mi[…………….

……………]me wæs min ti[…..

……………………

5 …]d ic on staðol[………………..

……….]um geong, swa[……….

……………..]seþeana

oft geond [………………..]fgeaf,

ac ic uplong stod, þær ic [………]

10 ond min broþor; begen wæron hearde.

Eard wæs þy weorðra þe wit on stodan,

hyrstum þy hyrra. Ful oft unc holt wrugon,

wudubeama helm wonnum nihtum,

scildon wið scurum; unc gescop meotud.

15 Nu unc mæran twam magas uncre

sculon æfter cuman, eard oðþringan

gingran broþor. Eom ic gumcynnes

anga ofer eorþan; is min agen bæc

wonn ond wundorlic. Ic on wuda stonde

20 bordes on ende. Nis min broþor her,

ac ic sceal broþorleas bordes on ende

staþol weardian, stondan fæste;

ne wat hwær min broþor on wera æhtum

eorþan sceata eardian sceal,

25 se me ær be healfe heah eardade.

Wit wæron gesome sæcce to fremmanne;

næfre uncer awþer his ellen cyðde,

swa wit þære beadwe begen ne onþungan.

Nu mec unsceafta innan slitað,

30 wyrdaþ mec be wombe; ic gewendan ne mæg.

Æt þam spore findeð sped se þe se[…

………..] sawle rædes.

Translation:

I grew where I s[……………………

……..]and summer mi[…………….

……………]me was my ti[…..

……………………

…]d I in the position[………………..

……….]um young, so[……….

……………..] nevertheless,

often throughout [………………..]fgave,

but I stood straight where I [………]

and my brother. We were both hardened.

Our shelter was worthier, adorned more highly,

as the two of us stood on top. The forest always protected us,

on dark nights, its helm of arboreal branches made a shield

against downpours. The Almighty molded us.

Now our kinsmen, our younger brothers

must come after us, and snatch away

our shelter. I am the only human individual

left in the world. My own back is

murky and marvelous. I stand on wood,

on the border of the shield/on the edge of the table/on the margin of the page.(1)

Mi hermano no está aquí.(2)

But I have to guard the position, brotherless

on the border of the shield/on the edge of the table/on the margin of the page.(3)

I must stand unmoved.

No sé dónde mi hermano debe habitar,(4) possessed by men, their property

in what quarter of the world

he who used to shelter high by my side.

We two were one when waging war.

Yet neither could make his valor known

as we were both no good when it came to battle.

Now some degenerates slit my insides,

tear into my abdomen. I cannot escape.

Following these traces finds abundance who […

………..] advantage to the soul.

Click to show riddle solution?

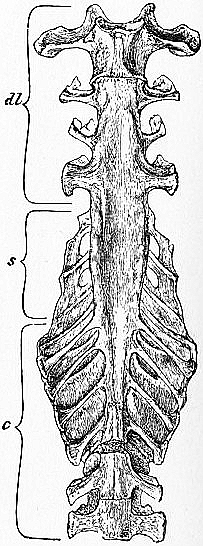

Antler, Inkhorn, Horn, Body and Soul

Notes: This riddle appears on folios 129r-129v of The Exeter Book.

The above Old English text is based on this edition: Elliott van Kirk Dobbie and George Philip Krapp, eds, The Exeter Book, Anglo-Saxon Poetic Records 3 (New York: Columbia University Press, 1936), pages 239-40.

Note that this edition numbers the text Riddle 84: Craig Williamson, ed., The Old English Riddles of the Exeter Book (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1977), pages 116-17.

Translation Notes:

(1) and (3) Please see the commentary for more information regarding this multiple translation.

(2) and (4) Likewise, an explanation of the parts in Spanish, and my reason for their use, can be found in the commentary.

Tags:

anglo saxon

exeter book

riddles

old english

solutions

riddle 88

denis ferhatovic

Related Posts:

Exeter Riddle 60

Exeter Riddle 72

Exeter Riddle 83

Commentary for Exeter Riddles 79 and 80

MEGANCAVELL

Date: Fri 31 Aug 2018Matching Riddle: Exeter Riddles 79 and 80

Riddle 79/80 is an unpopular little fella. You’d think that being a relatively unproblematic text in the middle of a fire-damaged collection of riddles would throw some scholarly love in this poem’s direction! But, alas, Riddle 79/80 remains unpopular. I couldn’t find many articles on it at all, which means I’ve had to do some work myself (*shakes fist at riddlers-of-the-past).

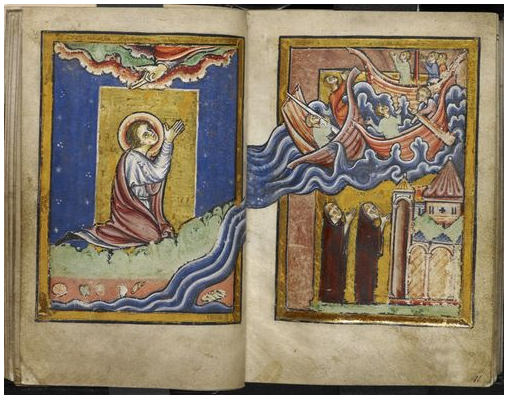

First things first: I guess I’d better address the opening lines. I said this was a relatively unproblematic text, after all, but the opening lines aren’t as smooth sailing as we might like. The first line ends with clear punctuation in the manuscript, and the next begins with a capitalized “IC,” which is what led Krapp and Dobbie to edit line 1 as “Riddle 79” and the rest as “Riddle 80.” But line 1 makes no sense as a complete riddle! It’s much more likely that this opening repetition is a false start, scribal error, or suggests that the scribe was copying from a defective text (Williamson, page 360).

Mercedes Salvador-Bello has recently argued that “this phase of the [manuscript’s] compilation was carried out in a rather awkward and rushed way. It seems to me that the scribe of the Exeter exemplar was probably rewriting and improvising as (s)he copied the riddles from the sources at hand” (pages 399-400). I like the idea of an improvising scribe meddling with an earlier version of this riddle. I also like that Salvador-Bello doesn’t jump to any conclusions about the gender identity of the scribe. Take THAT, patriarchy!

Ahem.

But what, I hear you asking, is this riddle actually about? What’s the solution, Queen of Riddlers? Impart upon us thy wisdom, Mighty and Great One! (okay, I’m willing to admit that the audience in my mind may not be quite the same as the *actual* audience of this post, but please leave me to my illusions)

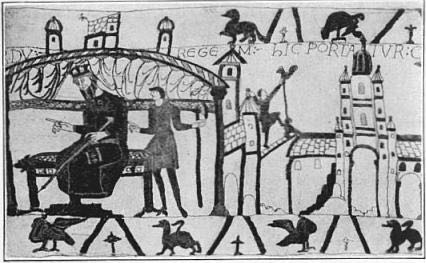

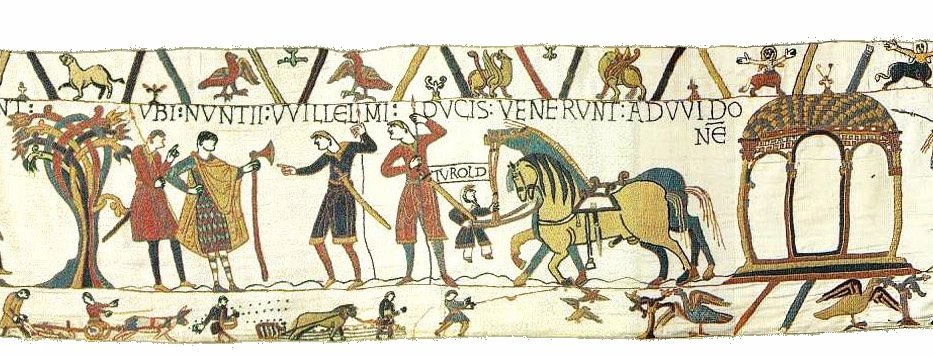

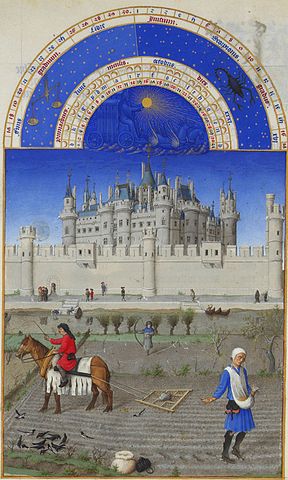

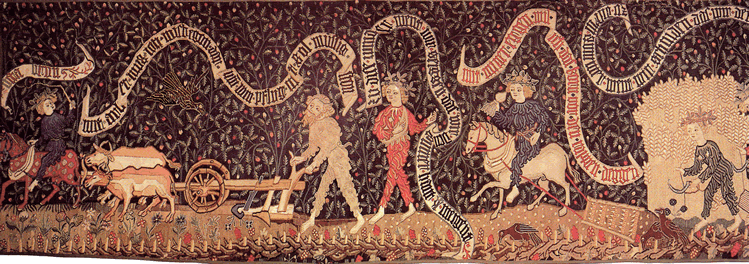

Well, most people reckon this is a horn riddle, though several birds of prey and various weapons have also had a look in. All that companion-y stuff, not to mention the queenly handling of the object in question, pretty clearly signals a solution of heroic importance. The reason Horn has gained momentum is because of the multiple uses such an object could be put to: it can be used for sounding in battle – so it’s a prince’s or king’s companion, rides with an army and has a harsh tongue (i.e. it’s loud). Think Boromir and the horn of Gondor.

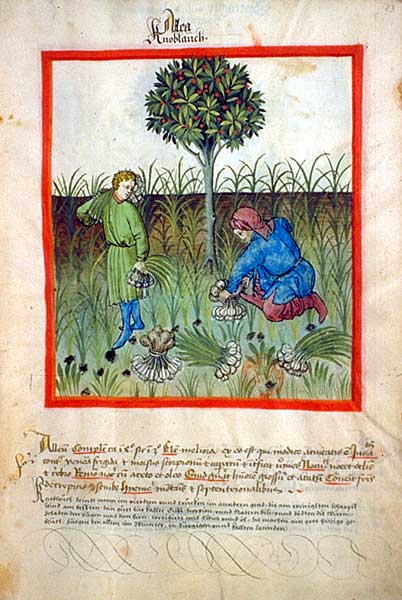

The riddle object leads a double life, since it can also be used as a drinking horn – fill that horn up with mead, and you’re all set for a nice little ritual or raucous celebration. Coincidentally, if it’s mead that’s being referred to in line 7’s Hæbbe me on bosme þæt on bearwe geweox (I have in my bosom what waxed in a wood), then we have a pretty good parallel in Riddle 27’s reference to a solution that’s brungen of bearwum (brought from forests). Riddle 27 is, after all, usually solved as Mead.

But back to Riddle 79/80. Line 3’s talk of the object being frean (beloved) to its lord may speak not only to its value, but also to the intimate nature of a horn’s use – drinking from it or sounding it means kissing it, in a way. And we’ve seen that sort of thing elsewhere. Do you remember all the way back to Riddle 14? That riddle described a horn in very similar terms, and had men kissing it in line 3b. And then there’s Riddle 63’s glass beaker. Well, that object was configured as a high-status woman being kissed and pressed by a tillic esne (capable servant). In Riddle 79/80 we have a swapping of gender roles, so this riddle object becomes a heroic and masculine figure being handled by a high-status lady. And this leads me to a second point: riddles related to drinking vessels are often more than a little eroticized.

These sorts of riddles also frequently describe an interplay between different sexes in the hall, which makes me think of the (far less titillating) exchange in Beowulf:

Eode Wealhþeow forð,

cwen Hroðgares, cynna gemyndig,

grette goldhroden guman on healle,

ond þa freolic wif ful gesealde

ærest Eastdena eþelwearde (612b-16)

(Wealhtheow went forth, Hrothgar’s queen, mindful of customs, the gold-adorned one greeted men in the hall, and the noble woman gave a cup first to the protector of the lands of the East-Danes)

No hanky panky whatsoever. How disappointing. But it does serve to demonstrate that ritualistic drinking in the hall was an important trope in the world of Old English poetry. Perhaps one that riddlers liked to poke fun at…

And speaking of fun: I reckon there’s a fairly meta view of poetic performances going on toward the end of Riddle 79/80. These lines describe the object giving a reward to a woðboran (speech-bearer) for words and a song, suggesting that the object itself gives the reward (as opposed to it being given *as* the reward, which seems to rule out any weapon-based solutions). I take this as the mead-horn being passed to a poet as a reward for a good recitation. I can’t help but wonder if the riddler was calling for a little treat too!

Come to think of it…it’s Friday and I would also like a treat…

References and Suggested Reading:

Davis, Adam. “Agon and Gnomon: Forms and Functions of the Anglo-Saxon Riddles.” In De Gustibus: Essays for Alain Renoir. Edited by John Miles Foley. New York: Garland, 1992, pages 110-50, esp. 140-2.

Salvador-Bello, Mercedes. Isidorean Perceptions of Order: the Exeter Book Riddles and Medieval Latin Enigmata. Morgantown: West Virginia University Press, 2015.

Swaen, A.E.H. “The Anglo-Saxon Horn Riddles.” Neophilologus, vol. 26, issue 4 (1941), pages 298-302.

Williamson, Craig, ed. The Old English Riddles of the Exeter Book. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1977.

Tags: anglo saxon exeter book riddles old english solutions riddle 79 riddle 80

Related Posts:

Commentary for Exeter Riddle 14

Commentary for Exeter Riddle 27

Commentary for Exeter Riddle 63