Exeter Riddle 66

MEGANCAVELL

Date: Mon 04 Sep 2017Matching Commentaries: Commentary for Exeter Riddle 66

This translation is by Erin Sebo, lecturer in English at Flinders University in Australia. Erin is especially interested in wisdom literature, heroism and the history of emotions (so, all the good stuff!).

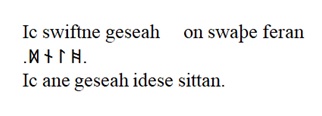

Ic eom mare þonne þes middangeard

læsse þonne hondwyrm, leohtre þonne mona,

swiftre þonne sunne. Sæs me sind ealle

flodas on fæðmum ond þes foldan bearm,

grene wongas. Grundum ic hrine,

helle underhnige, heofonas oferstige,

wuldres eþel, wide ræce

ofer engla eard, eorþan gefylle,

ealne middangeard ond merestreamas

side mid me sylfum. Saga hwæt ic hatte.

I am greater than this middle-earth,

less than a hand-worm, lighter than the moon,

swifter than the sun. All the seas’ tides are

in my embraces and the earthen breast,

the green fields. I touch the foundations,

I sink under hell, I soar over the heavens,

the home of glory; I reach wide

over the homeland of angels; I fill the earth abundantly,

the entire world and the streams of the oceans

with myself. Say what I am called.

Notes:

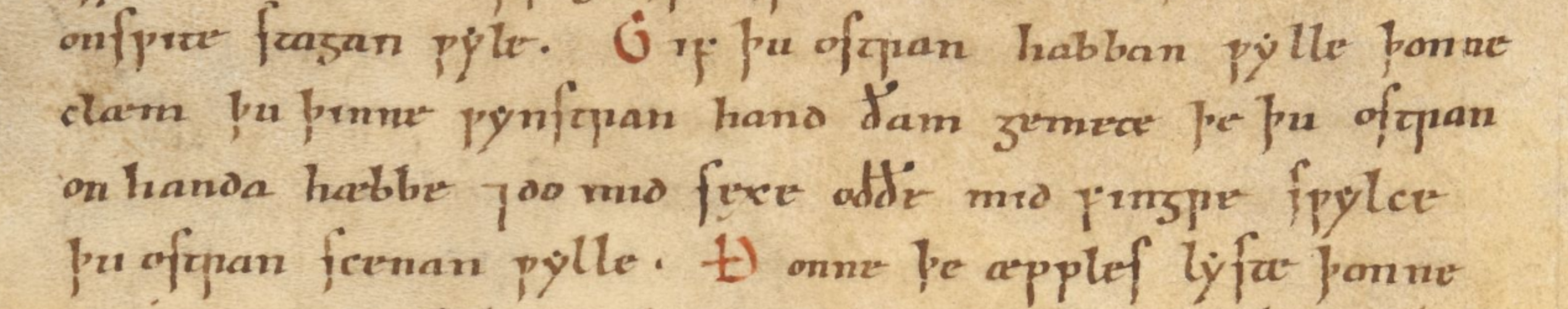

This riddle appears on folios 125r-125v of The Exeter Book.

The above Old English text is based on this edition: Elliott van Kirk Dobbie and George Philip Krapp, eds, The Exeter Book, Anglo-Saxon Poetic Records 3 (New York: Columbia University Press, 1936), pages 230-1.

Note that this edition numbers the text Riddle 64: Craig Williamson, ed., The Old English Riddles of the Exeter Book (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1977), pages 105-6.

Tags: anglo saxon exeter book riddles old english solutions riddle 66

Related Posts:

Commentary for Exeter Riddles 1-3

Exeter Riddle 40

Exeter Riddle 7

Commentary for Exeter Riddle 66

MEGANCAVELL

Date: Tue 26 Sep 2017Matching Riddle: Exeter Riddle 66

This commentary post is once again by Erin Sebo at Flinders University in Australia. Take it away, Erin!

Riddle 66 is the second of the three “Creation Riddles” in the Exeter Book (Riddles 40, 66 and 94). Although it’s common to find several riddles with the same answer – or which seem to have the same answer – the creation riddles are unusual because they are all versions of the same riddle, just “edited” a bit. (Or in the case of Riddle 94, a lot.)

All riddles have a trick at their heart: a paradox, an ambiguity, a misdirection; the thing that makes the riddle hard to solve. It’s the thing that makes a riddle a riddle.

Riddles 40, 66, and 94 and their parent, Aldhelm’s epic Latin De Creatura (the last riddle in his riddle sequence), all have the same trick and the same solution. They’re same riddle, even though the words are different.

If the number of surviving versions is anything to go on (and maybe it’s not), it was the most popular riddle in early England. Or, if not the most popular, perhaps the most important? The best known? Whatever it was, the complier(s) of the Exeter Book thought it was worth the vellum to write out different versions of it.

But it’s not how Riddles 40, 66, and 94 are the same that’s the most interesting bit; what’s really interesting is how they’re different. Each version of this riddle gives us a slightly different insight into how the world was imagined. In the case of Riddle 66, it gives us an insight into how ordinary people, or at least some ordinary people, imagined the world. That’s rare in early medieval texts.

De Creatura was written by a theologian (Aldhelm), and Riddle 40 was translated by someone who was at least educated enough to read Latin, but from the way Riddle 66 has been adapted, made shorter, more focused, more memorable, it may well have spent time in the oral tradition, being told and retold. For example, the litany of oppositions, often illustrated by obscure or exotic animals or materials and underpinned by allusions to scripture, of Riddle 40, is replaced by simple, broad elemental images. On the other hand, the memorable and unusual word hondwyrm is preserved. (Often something that’s characteristic will stick in people’s minds so these elements tend to survive.) Otherwise, very few of the same details survive, just the overall idea, which is typical of the way oral texts change. So while most of the Exeter Riddles are composed and meant to be read this one was probably told – and given the lack of details which reveal specialist knowledge, not to mention the highly unorthodox (potentially heretical) view of the world, it may well have been told by ordinary people.

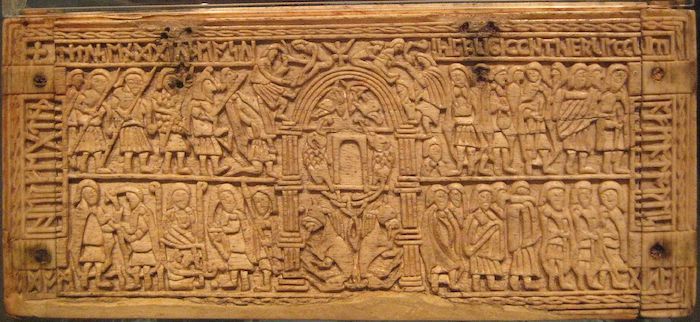

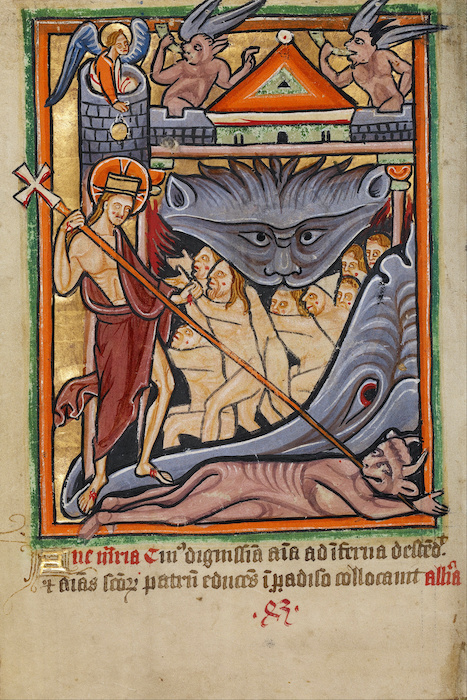

So, how did the ordinary medieval person of this riddle imagine the world? The most striking thing is that the riddle doesn’t mention God. Riddle 40 imagines Creation more or less like this:

13th-century Psalter World Map from a manuscript called British Library Add. MS 28681, via Wikimedia Commons (Public Domain).

God on the outside, who healdeð ond wealdeð (holds and controls) (Riddle 40, line 5a), is keeping an eye on things. But in Riddle 66, Creation is imagined not as a collection of all the things that make up the physical and/or metaphysical worlds, but rather as a force, racing around the world, diving under the seas. Unlike Riddle 40 which has a series of dichotomies, with a positive and a negative side, Creation in Riddle 66 is made up of excellent qualities only: it’s fast and bright and can reach the angels. It’s expansive. Although creation says it’s laesse, most of the riddle is about how it fills the oceans and extends through the fields. By the same token, it dives under hell but there’s no mention of devils, only of soaring as high as angels. It’s an optimistic force. And it’s not clear what its relationship to God is because this is never quite articulated. It is described more like an irresistible force, racing freely around the space it inhabits, than an expression of God. It does not describe itself as enacting God’s plan or acting on his orders. And the fact it only reaches angels, not God himself seems to suggest that they are not connected.

It’s an unusual idea of the world.

And it’s as surprising in its details as it is in its overall conception and I want to end with one of its strangest, tiniest details; tiny hondwyrm. It seems to be a parasitic insect but we’re not sure what kind exactly. And it’s also the only animal mentioned. There are no birds or fish or mammals – including humans. So, I’ll finish the commentary on this riddle with a question – why is this tiny insect more important than all other creatures?

References and Suggested Reading:

Michelet, Fabienne. Creation, Migration and Conquest: Imaginary Geography and Sense of Space in Old English Literature. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2006.

Neville, Jennifer. Representations of the Natural World in Old English Poetry. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1999.

Sebo, Erin. In Enigmate: The History of a Riddle from 400-1500. Dublin: Four Courts Press, 2017. (coming out in October!)

Wehlau, Ruth. The Riddle of Creation: Metaphor Structures in Old English Poetry. New York: Peter Lang, 1997.

Tags: exeter book riddles old english solutions riddle 66 erin sebo

Related Posts:

Commentary for Exeter Riddle 40