Exeter Riddle 54

MEGANCAVELL

Date: Tue 23 Aug 2016Matching Commentaries: Commentary for Exeter Riddle 54

This post comes to us from Andrea Di Carlo, who’s a PhD candidate at Pisa University. Andrea’s research interests include the “obscene” riddles from the Exeter Book, and Protestant medievalism in Renaissance England. Take it away, Andrea:

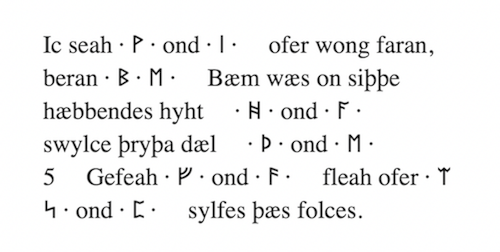

Hyse cwom gangan, þær he hie wisse

stondan in wincsele, stop feorran to,

hror hægstealdmon, hof his agen

hrægl hondum up, hrand under gyrdels

5 hyre stondendre stiþes nathwæt,

worhte his willan; wagedan buta.

Þegn onnette, wæs þragum nyt

tillic esne, teorode hwæþre

æt stunda gehwam strong ær þon hio,

10 werig þæs weorces. Hyre weaxan ongon

under gyrdelse þæt oft gode men

ferðþum freogað ond mid feo bicgað.

There came walking a young man, to where he knew

she was standing in a corner. From afar he went,

the resolute young man, heaving his own clothing

with his hands, pushing something stiff

5 under her girdle while she was standing there,

worked his will; the two of them shook.

A retainer hastened, his capable servant

was useful sometimes; still, at times, he grew tired

though stronger than her at first,

10 weary due to work. Under the girdle,

there began to grow what good men often

love in their hearts and buy with money.

Notes:

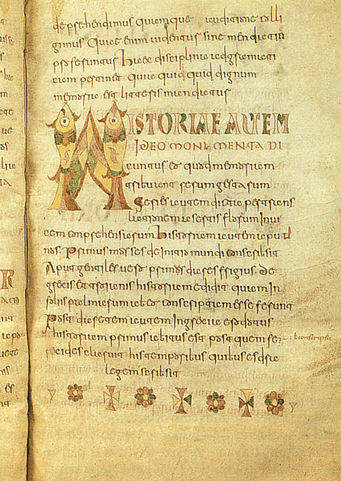

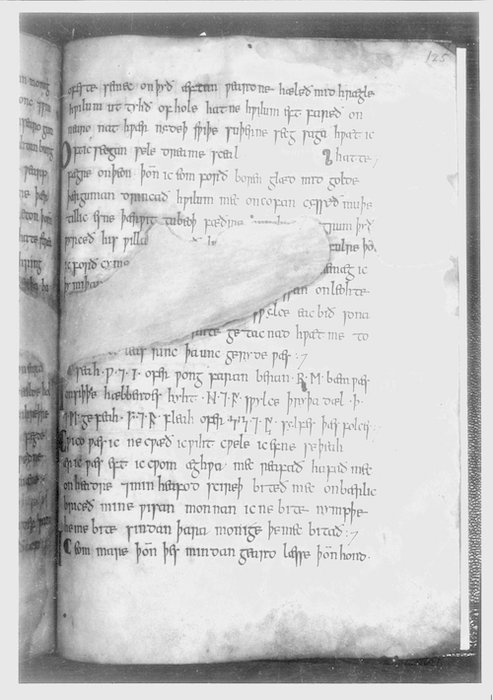

This riddle appears on folios 113v-114r of The Exeter Book.

The above Old English text is based on this edition: Elliott van Kirk Dobbie and George Philip Krapp, eds, The Exeter Book, Anglo-Saxon Poetic Records 3 (New York: Columbia University Press, 1936), pages 207-8.

Note that this edition numbers the text Riddle 52: Craig Williamson, ed., The Old English Riddles of the Exeter Book (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1977), page 100.

Tags: anglo saxon exeter book riddles old english solutions riddle 54

Related Posts:

Commentary for Exeter Riddle 88

Commentary for Exeter Riddle 54

Commentary for Exeter Riddle 61

Commentary for Exeter Riddle 54

MEGANCAVELL

Date: Thu 22 Feb 2018Matching Riddle: Exeter Riddle 54

For this post, we’re going to experiment with a new commentary style. I’m all for collaboration, so Andrea Di Carlo and I are going to take turns talking about Riddle 54. Will it work? You can be the judge of that! (but don’t actually judge us, because our egos are too fragile for all that)

Let’s start with the basics: what are the “obscene” riddles and how does Riddle 54 fit in?

Andrea: Over the last few decades, the riddles of the Exeter Book have attracted a lot of scholarship, especially after the critical reviews carried out by Mercedes Salvador-Bello, Glenn Davis, Patrick Murphy and Ruth Evans. If, in 1910, Frederick Tupper had rejected any type of unsavoury interpretation and overruled the category “obscene riddles,” George Phillip Krapp and Elliott van Kirk Dobbie later made allowances for euphemistic wording and images, and acknowledged that obscene content had to be taken into account.

Riddle 54 perfectly fits into this category because its imagery is certainly problematic and far from ambiguous. Krapp and Dobbie solve the riddle as “churn” (page 188), relying on the earlier suggestion of Moritz Trautmann. The backdrop of the obscene riddles tends to be mundane, as is the case with the start of Riddle 54: readers follow the progress of a young man travelling toward a woman, only to hear that, when he arrives in the corner where the woman stands, he thrusts stiþes nathwæt (line 5b) (something stiff) under her girdle.

Megan: Okay, so pretty obviously euphemistic then. While we can translate nathwæt as just “something,” the nat part of the compound is actually from the contracted verb, nytan, that is: ne + witan (to know not). In other words, it means something like “a stiff know-not-what.” This is a pretty obvious attempt to avoid saying what it is the poet means, which just screams euphemism! Nathwæt also appears in Riddle 45 and Riddle 61, both of which are interested in sex in their own right.

So, the word is a dead giveaway that we’re definitely looking at a rude riddle.

Andrea: What else are we readers supposed to think? It’s pretty clear that the anonymous riddle-composer is showing us a short scene of sexual intercourse (suspicion is only aroused further by the use of wagedan in line 6, which means “shake” or “shag,” and by the tillic esne (capable servant) hastening in lines 7-8a). This idea is emphasised by Murphy (pages 184-195) and Evans (page 28), whose interpretations of the text are based upon these sequences of obscene and potentially aggressive images: the hyse (young man) of line 1a worhte his willan (line 6a) (worked his will), while the female figure stands there.

Megan: So, is this a disturbing example of sex where the woman is simply the object of the man’s desire, or could there be something more going on here? Well, Murphy actually provides an alternative interpretation to the two-people-having-sex-in-a-corner reading. He reminds us that we shouldn’t confuse the grammatical and natural gender of pronouns – that is, the poet never actually describes the female character (while other rude riddles, like Riddle 25 and Riddle 45, do include more elaborate descriptions), and so she might not be a woman at all.

The female pronouns (hio/hie/hire, i.e. she/her) could also be applied to objects that are grammatically feminine…which, coincidentally, Old English cyrn is. So, if we read every reference to “she/her” as “it” instead and swap the translation “belt” for “girdle,” then maybe we’re actually witnessing a young man working his will on his “capable servant” all by himself. This certainly makes the joke a lot less aggressive and so, I’d say, funnier. And it just gets more amusing when we read this potential masturbation scene alongside the more wholesome butter churn interpretation.

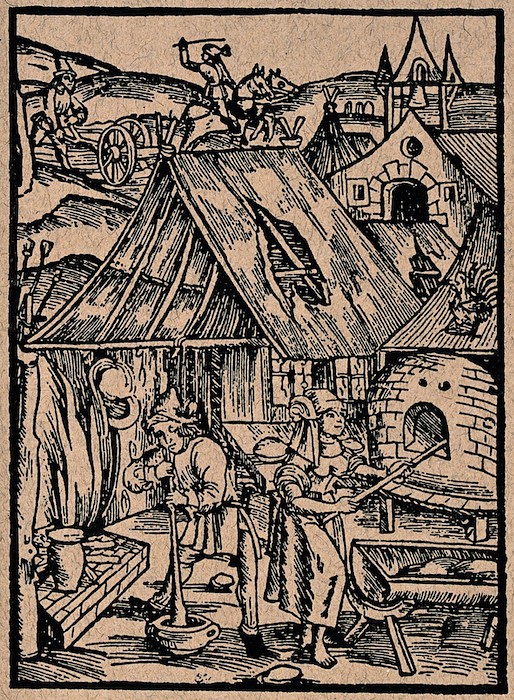

Andrea: Yes! We should always expect some sort of a twist in the Old English riddles. And the turning point takes place in the last line, where our sexual assumptions are quashed and we’re brought back to a reality that both encourages and rejects the double entendre. In lines 11-12 we hear that under the woman’s girdle (or man’s belt) grows what men mid feo bicgað (buy with money). Surely, there’s no euphemistic way to read this financial transaction?! With these lines, the sexual reading of Riddle 54 is dispelled and we find that the author was simply referring to the making of butter in a churn.

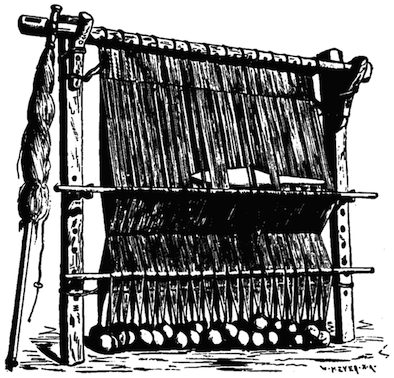

Here are some Icelandic butter churns on display at a museum Megan once visited. Sadly, she has no idea where she saw these bad boys. Possibly in the south of Iceland?

Megan: If we accept that we’re hearing about a cyrn or churn, then the riddle also provides a useful corrective to any food prep-based gender assumptions we might want to make. It’s tempting to assume that all food production was a female task in early medieval England, and certainly much of women’s work did involve preparing food. We do, for example, have a reference to a female cheese-maker whose duties also involved making butter from the eleventh-century law-text known as the Rectitudines Singularum Personarum (Rights of Different People).

It reads: cyswyrhtan gebyreð hundred cyse, & þæt heo of wringhwæge buteran macige to hlafordes beode (a hundred cheeses are allotted to the cheese-maker, and that she makes butter from the whey pressed out of cheese for the lord’s table (Liebermann, vol. 1, page 451, no. 16). The feminine ending attached to the cheese-maker here tells us that she’s female. But the method of preparation – of cheese first and then butter – also tells us that the raw material is likely sheep’s milk (Banham and Faith, pages 111-12). Could this be important?

Because, after all, the person doing the churning here in Riddle 54 is definitely male. And he’s not the only man to own up to doing a bit of churning on the side. In fact, he reminds me of the shepherd in Ælfric’s Colloquy (a dialogue-style, bilingual text aimed at teaching Latin to youngsters in early medieval England). After the teacher asks the pupil assigned the role of shepherd what work he does, the pupil replies that he watches over the sheep in their pastures, milks them, etc., and finishes with the statement: ge cyse ge buteran ic do, ond ic eom getrywe hlaforde minum (I make both butter and cheese, and I am faithful to my lord) (Ælfric, page 22). So, perhaps it makes sense to think of farming as the task of a household rather than dividing specific bits and pieces of it down gender lines.

Someone had better tell the be-skirted churners at the Durham Medieval Family Fun Weekend I attended last year to get their male collaborators to help out a bit more!

The butter churn on show at the Medieval Family Fun Weekend, Durham Cathedral, August 2015.

So, we’ve heard about the various ways of reading this riddle’s sexual encounter, and we’ve heard a bit about churning butter (which is really tiring, hard work, by the way!). But what’s the take-home point of this riddle, then?

Andrea: I think it’s important to note that the riddles capitalise on double entendre and dubiety, because it’s in their nature to intellectually challenge and defy readers. “No sex, please, we’re Anglo-Saxons,” as Hugh Magennis famously wrote some time ago! I’d argue that sexual imagery or sexually laden content in the riddles conveys a more domestic and less remote picture of the past, while also challenging commonplaces about sexual life in medieval Europe.

In the end, mystifying or nonplussing the audience is the main target of the riddle-composer and this one perfectly manages to play his/her cards right: the poet tricks us into believing we’re viewing sexual intercourse in the opening lines, only to undercut our assumptions at the end by making it clear that it wasn’t sex at all, but the making of something that can be bought and sold (butter, of course!). And, after all, this is the nature of riddles, to engage participants in a mental and intellectual process that’s supposed to enrich their knowledge, as Krapp and Dobbie maintain. Or, in this case, to baffle them!

References and Suggested Reading:

Ælfric of Eynsham. Ælfric’s Colloquy. Edited by G.N. Garmonsway. London: Methuen, 1939.

Banham, Debby, and Rosamond Faith. Anglo-Saxon Farms and Farming. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2014.

Davis, Glenn. “The Exeter Book Riddles and the Place of Sexual Idiom in Old English Literature.” In Medieval Obscenities. Edited by Nicola McDonald. York: York Medieval Press, 2006, pages 39-54.

Evans, Ruth, ed. A Cultural History of Sexuality in the Middle Ages. London: Bloomsbury, 2014.

Krapp, George Philip, and Elliott Van Kirk Dobbie, eds. The Exeter Book, Anglo-Saxon Poetic Record, vol. 3. New York: Columbia University Press, 1936.

Liebermann, F., ed. Die Gesetze der Angelsachsen. 3 vols. Halle: Max Niemeyer, 1903-16.

Magennis, Hugh. “‘No Sex Please, We’re Anglo-Saxons’? Attitudes to Sexuality in Old English Prose and Poetry.” Leeds Studies in English, vol. 26 (1995), pages 1-27.

Murphy, Patrick J. Unriddling the Exeter Riddles. University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, 2011.

Salvador-Bello, Mercedes. “The Key to the Body: Unlocking Riddles 42-46.” In Naked Before God: Uncovering Body in Anglo-Saxon England. Edited by Benjamin C. Withers and Jonathan Wilcox. Morgantown: West Virginia University Press, 2003, pages 60-96.

Trautmann, Moritz. “Alte und Neue Antworten auf altenglische Rätsel.” Bonner Beiträge zur Anglistik, vol. 19 (1905), pages 167-215.

Tupper, Frederick, Jr., ed. The Riddles of the Exeter Book, Boston: Ginn, 1910.

Tags: anglo saxon exeter book riddles old english solutions riddle 54 andrea di carlo

Related Posts:

Commentary for Exeter Riddle 25

Commentary for Exeter Riddle 45

Commentary for Exeter Riddle 61