Exeter Riddle 22

MATTHIASAMMON

Date: Mon 21 Apr 2014Matching Commentaries: Commentary for Exeter Riddle 22

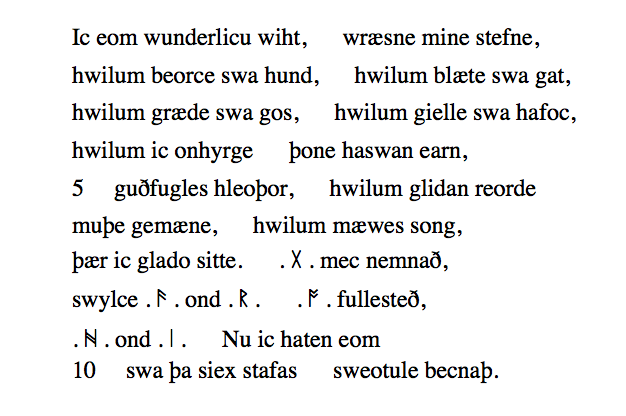

Ætsomne cwom LX monna

to wægstæþe wicgum ridan;

hæfdon XI eoredmæcgas

fridhengestas, IIII sceamas.

5 Ne meahton magorincas ofer mere feolan,

swa hi fundedon, ac wæs flod to deop,

atol yþa geþræc, ofras hea,

streamas stronge. Ongunnon stigan þa

on wægn weras ond hyra wicg somod

10 hlodan under hrunge; þa þa hors oðbær

eh ond eorlas, æscum dealle,

ofer wætres byht wægn to lande,

swa hine oxa ne teah ne esna mægen

ne fæthengest, ne on flode swom,

15 ne be grunde wod gestum under,

ne lagu drefde, ne on lyfte fleag,

ne under bæc cyrde; brohte hwæþre

beornas ofer burnan ond hyra bloncan mid

from stæðe heaum, þæt hy stopan up

20 on oþerne, ellenrofe,

weras of wæge, ond hyra wicg gesund.

Together 60 men came

riding to the bank on horses;

11 horsemen had

noble steeds, 4 had white ones.

5 The warriors could not pass over the water,

as they intended, but the sea was too deep,

the terrible tumult of the waves, the banks too high,

the streams too strong. Then the men began

to climb up on the wagon together with their horses,

10 to load under the pole; then the wagon carried the horses,

mounts and men, proud in spears,

to land across the bay of the water,

in such a way that no ox pulled it, nor the strength of slaves,

nor a draught horse, nor did it swim on the water,

15 nor did it wade along the ground under its guests,

nor did it disturb the waters, nor fly in the air,

nor turned back; nevertheless it brought

the warriors over the stream, and their horses with them

from the high bank, so that they stepped up

20 onto the other, strong in courage,

the men from the waves, and also their horses, unharmed.

Notes:

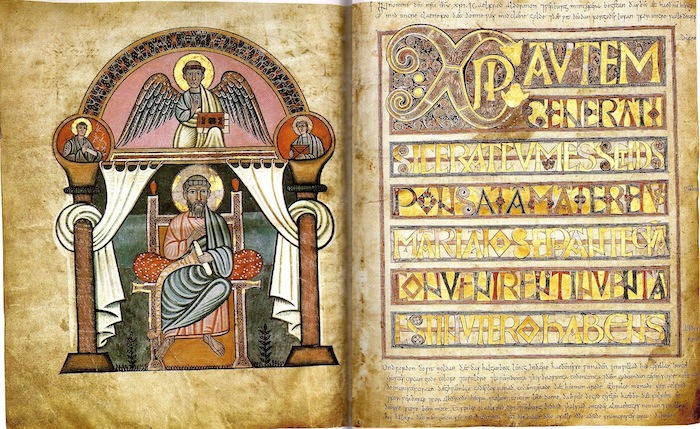

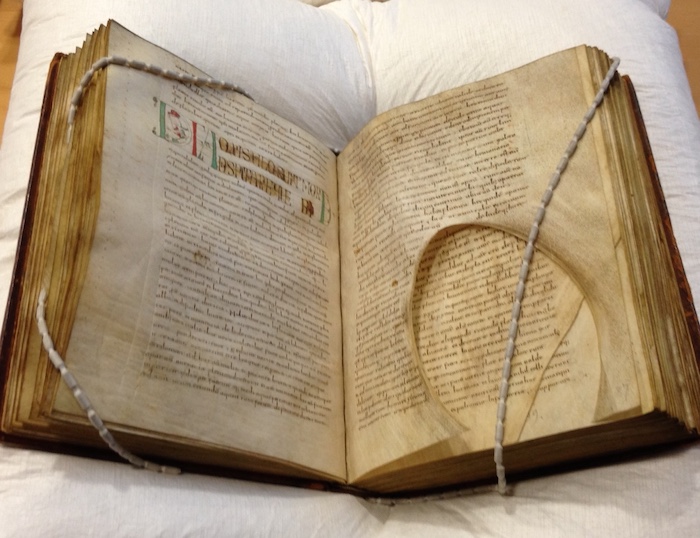

This riddle appears on folios 106r-106v of The Exeter Book.

The above Old English text is based on this edition: Elliott van Kirk Dobbie and George Philip Krapp, eds, The Exeter Book, Anglo-Saxon Poetic Records 3 (New York: Columbia University Press, 1936), pages 191-2.

Note that this edition numbers the text Riddle 20: Craig Williamson, ed., The Old English Riddles of the Exeter Book (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1977), pages 80-1.

Tags: anglo saxon exeter book riddles old english solutions riddle 22

Related Posts:

Exeter Riddle 3

Exeter Riddle 26

Exeter Riddle 49

Commentary for Exeter Riddle 22

MEGANCAVELL

Date: Wed 07 May 2014Matching Riddle: Exeter Riddle 22

This riddle’s commentary is a guest post from the stellar David Callander. David is a PhD student at the University of Cambridge, where he works on early medieval Welsh and English poetry. Take it away, David!

If you’re anything like me, this riddle will have completely foxed you. Different possibilities are gradually taken away until we’re left wondering, what on earth could this be? Or not on earth, perhaps.

First of all, we’re told that we’re dealing with LX men riding on horseback (Arabic numbers weren’t used in England yet, so the residents of early medieval England were stuck with Roman numerals.) Instead of moving on to describe different aspects of these men, we’re told a short story about them trying to cross a river. They want to cross this river, but are held back by the atol yþa geþræc, the ‘terrible tumult of the waves’. So then this wægn (it is what it looks like) turns up and, with a conveniently introduced pole, both ‘mounts and men’ are borne cheerfully over the water. But they do this in a seemingly impossible way – it did not disturb the water, nor fly in the air (so the Wind’s out), and also they weren’t pulled by the strength of slaves, or beasts of burden (13-14). This concludes with a happy ending, the men and horses have reached the greener grass of the far bank gesund (‘unharmed’ – the word is still used in Modern German and forms the first part of Gesundheit.) To me it all sounds a bit like punting.

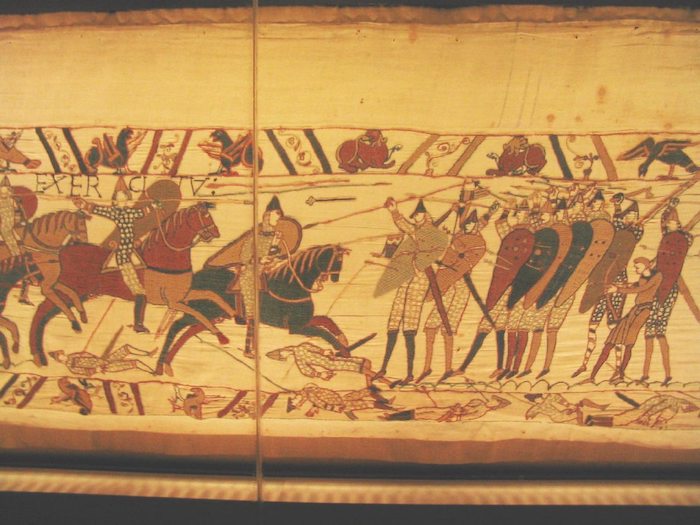

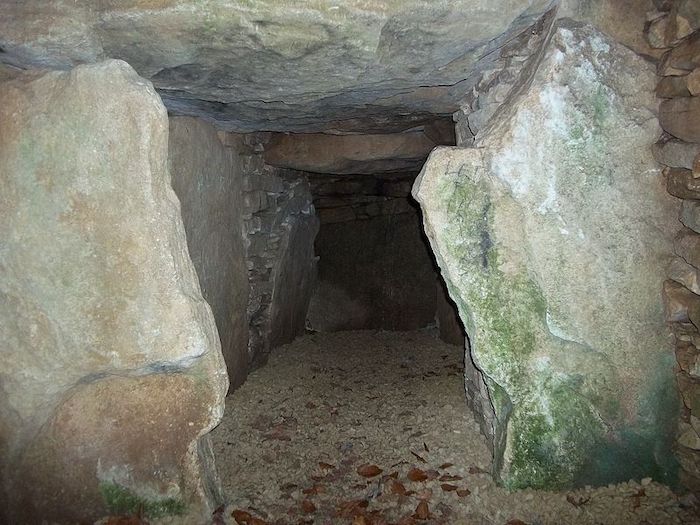

Photo (by Evans1551) from Wikimedia Commons (licence: CC BY-SA 3.0).

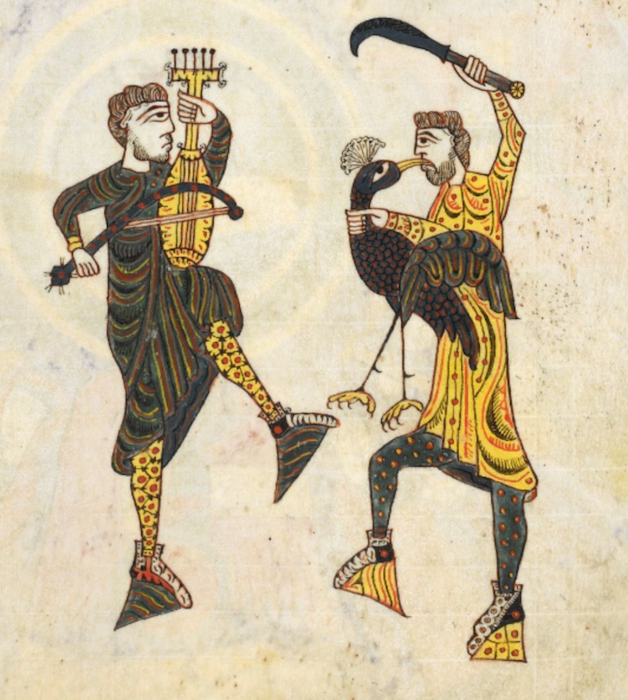

So, a lovely story, but we aren’t really left any the wiser as to what is being described, and there’s just so much going on! What are the men and horses, and what’s the teleporting wagon doing? And why are there sixty men, eleven with noble steeds and four with white ones? Presumably the rest had to make do with tiny Viking horses:

Photo (by Andreas Tille) from Wikimedia Commons (licence: CC BY-SA 3.0).

Well, as you might expect, scholars have been arguing about this for at least 150 years. What can cross water, but not in the sky nor through the water itself? We are compelled to look up.

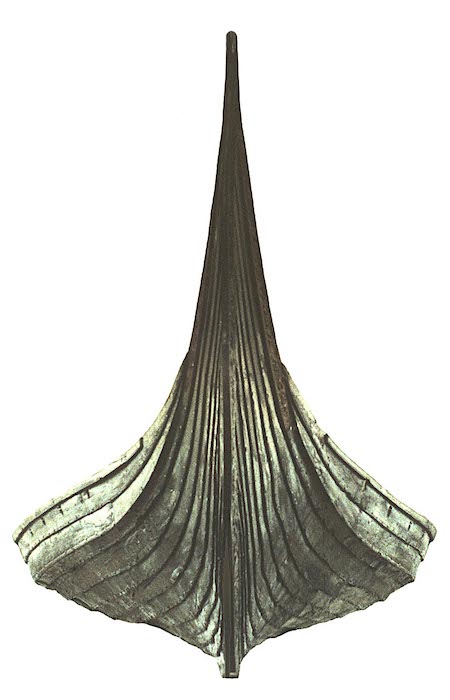

For some of us nowadays, it can be easy to forget the stars. But for the people of early medieval England they would have been vivid in the unclouded sky, without fumes and smog to blot them out. The constellation we now know as the Big Dipper (Ursa Major) was then known as Carles wæn (literally "a churl’s wagon"). This seems to have represented a wagon with a single pole, as L. Blakeley explains. Ælfric refers to how this constellation goes up and down both by day and by night in his De temporibus anni. The constellation under the “Wain” (Canes Venatici) consists of eleven stars visible to the naked eye, four of which Blakeley sees as particularly bright (the eleven noble steeds and four white ones.) Patrick Murphy has preferred to see the constellation Draco here, which, conveniently, consists of fifteen stars.

Can you see it? Photo (by adkiscool) from Deviant Art.

But why sixty horsemen altogether? Marijane Osborn makes the ingenious suggestion that this refers to sixty days after the winter solstice, when the position of the Big Dipper in relation to the pole would mark the seasons, or it could just be used more loosely to refer to many stars. Like other Old English riddles, this poem might draw upon Aldhelm’s Latin riddles (Riddle 53 in particular, which also refers to the Wain.)

Other solutions have been suggested, such as "month" and "bridge." A "month" (December in particular) was the earliest proposed solution, with the sixty days referring to the half-days of the month. It runs into a bit of trouble because it relies on counting feast days (seven) and Sundays (four, although there could be five) in terms of full days, rather than half-days like the other days of the month. It seems a bit of a leap to take this out of the riddle. A "bridge" would certainly have allowed the horsemen to cross the river without disturbing the water. But how would this explain the horsemen? And why would they have been stuck on one side of the water if there was already a bridge there?

One last tantalizing titbit. Classical writers refer to the Big Dipper as a plough (the constellation Boötes being the ploughman.) If we look at the first three riddles of the Exeter Book (unless we see them as one super-riddle), it seems that some of the riddles have been grouped together by theme. I wonder whether the idea of the Big Dipper as a plough was in the mind of a compiler when he decided to place the text after Riddle 21 (the Plough)?

References and Suggested Reading:

Ælfric. De Temporibus Anni. Ed. Heinrich Henel. Early English Text Society, vol. 213. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1942, section 9.6.

Blakeley, L. “Riddles 22 and 58 of the Exeter Book.” Review of English Studies, new series, vol. 9 (1958), pages 241-7.

Murphy, Patrick J. Unriddling the Exeter Riddles. PA: Pennsylvania State University Press, 2011, pages 111-23.

Osborne, Marijane. “Old English Ing and his Wain.” Neuphilologische Mitteilungen, vol. 81 (1980), pages 388-9.

Williamson, Craig, ed. The Old English Riddles of the Exeter Book. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1977, pages 201-4.

Tags: anglo saxon exeter book riddles old english solutions riddle 22 david callander

Related Posts:

Commentary for Exeter Riddle 53